Named after the cellist who helped to popularise his instrument in the US, the Piatigorsky International Cello Festival held its second quadrennial edition in May. Chloe Cutts was in Los Angeles and spoke to founder and artistic director Ralph Kirshbaum about his vision for the event

’I started with an idea for a programme that would build upwards: beginning with one of the greatest chamber works in the repertoire, Schubert’s Quintet, which has two cellos; followed by Brett Dean’s Twelve Angry Men, which has twelve cellos, and finishing with 100 cellos filling the stage at the Walt Disney Concert Hall for Villa-Lobos’s Bachianas Brasileiras no.1 for mass cello ensemble and the world premiere of a new work by the British composer Anna Clyne, Threads & Traces.’

Ralph Kirshbaum is describing the concept behind one of the centrepiece concerts at this year’s Piatigorsky International Cello Festival. It is a programme as bold and arresting as the Frank Gehry-designed Disney Hall – with its curvaceous petal-like shell and gregarious interior – and it perfectly encapsulates one of the veteran US cellist’s statements of intent: to intrigue concertgoers with the new, the much-loved and the wholly unexpected. If Gehry intended to surprise and demystify classical music with his architectural design, Kirshbaum has a similar outlook for the festival he founded and has directed since its Manchester incarnation, launched almost two decades ago. It is, he says, a vision very much aided and abetted by the festival format.

‘A festival audience is looking for, and curious about, works that they’re not familiar with,’ he says. ‘They’re hungry for it. There is something about a one- instrument festival that leads to this kind of total immersion – in the cello, the players and the repertoire. But this festival is a vehicle for something much bigger than just this one instrument – it is about the life force of music.’

Kirshbaum launched the Manchester International Cello Festival in 1988 when he was head of the cello department at the UK’s Royal Northern College of Music, and the gathering of cello stars, young artists, pedagogues and enthusiasts ran until 2007, when he moved to Los Angeles to take up the Gregor Piatigorsky chair in cello at the University of Southern California (USC) Thornton School of Music. Inspired by the flourishing West Coast classical music scene that greeted him, in 2011 he unveiled a successor festival with three partner institutions: the Thornton School, where most of the events were held, the Los Angeles Philharmonic and the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra. And what better way to launch the second edition than with the LA Phil at home in Disney Hall in three great works for cello and orchestra: the Elgar Concerto in a powerfully insightful reading by the Norwegian cellist Truls Mørk; Martinů’s buoyant Concerto no.1 (1955 version), brought joyfully to life by Argentine soloist Sol Gabetta; and the elusive Schelomo by Bloch, a ‘Hebrew rhapsody’ for cello and orchestra with Kirshbaum in the solo role.

‘Schelomo is so rarely played, and is a unique voice – a cross between a tone poem and a concerto in miniature,’ says the cellist. It is also a profoundly volatile, sensual and richly expressive piece, and is one of countless lesser-known corners of the cello repertoire that have found a platform at Kirshbaum’s festivals over the years. Having tested the LA waters with the first Piatigorsky Festival in 2011, he has made bolder strides into the hinterland with this year’s edition.

‘I have certainly taken more risks with repertoire compared to last time,’ he says. ‘There is one particular programme that I thought about for three years, which comprised three disparate and relatively unknown works related only by the cello and by their rather eclectic forms: the beautifully simple, almost naive Concerto for Cello and Wind Instruments by Ibert performed by Raphael Wallfisch; Gulda’s ebullient and quirky Concerto for cello and wind orchestra with cellist Li-Wei Qin; and Sofia Gubaidulina’s exploratory The Canticle of the Sun.’

David Geringas, the cellist protagonist in this last piece, has long championed contemporary Russian repertoire in the West, including works by Gubaidulina, whose Canticle is dedicated to Geringas’s teacher, Mstislav Rostropovich. Scored for cello, chamber choir, percussion and celesta, it explores the cello’s lowest possible range before instructing the player to abandon the instrument altogether, first for a bass drum, then a flexatone (played with a double bass bow), before returning to the cello. Geringas’s singular rendering gave the eerie impression of a method actor disappearing inside a character.

This programme alone illustrates a central point of the festival: to give oxygen to extraordinary and rarely programmed pieces. ‘It would be extremely unusual to hear any of these works in a programme, but to hear all three in one evening is virtually unheard of,’ says Kirshbaum. The same could be said of another beautifully conceived piece of programming, ‘Baroque Conversations’. Five concertos – by Platti, Vivaldi, Boccherini, Leo and C.P.E. Bach – were performed respectively by four very individual interpreters: Jean-Guihen Queyras, Colin Carr, Thomas Demenga and Giovanni Sollima, with Queyras returning in the Bach. Here was absolutely magnetic music making, stylishly and exuberantly delivered with seamlessly cohesive support from the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra.

‘Each festival takes on a life of its own,’ says Kirshbaum, who works closely with festival artists on repertoire choices, which in turn inform his programme concepts, including Baroque Conversations, the Concerto Concert [featuring Ibert, Gulda and Gubaidulina] and the final gala showcasing all of Beethoven’s works for cello. ‘If you’re not leading an audience to open up their horizons, if you’re just programming the same things, what are you accomplishing?’ Piatigorsky, who taught at the USC Thornton School and whose students Mischa Maisky, Jeffrey Solow, Raphael Wallfisch and Laurence Lesser numbered among the 25 international artists attending this year, would undoubtedly have agreed. He was an enthusiastic advocate of new works, but his repertoire included many classics too, and one of the great joys of an immersive festival like this is experiencing the familiar anew – Wendy Warner’s searingly honest Brahms Sonata op.38; Colin Carr full of judicious insight in Beethoven’s op.69 Sonata in the closing gala; and Yo-Yo Ma performing the Ave Marias of both Bach/Gounod and Schubert at Disney Hall – crowd pleasers for sure, but who else can communicate these works with such effortless generosity of spirit?

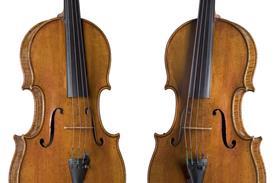

Elsewhere, the abundance of other festival highlights included the impeccable Calder Quartet in an infectiously spirited performance of Boccherini’s Quintet in C major op.28 no.4 with the irrepressible Italian cellist–composer Giovanni Sollima, who also gave an improvisation workshop that took students way out of their comfort zones and into a world of spontaneous music making; and Israeli–American Amit Peled – playing Pablo Casals’s 1733 Gofriller cello – in a recital that included Lera Auerbach’s Casals homage, La Suite dels Ocells based on Bach’s Cello Suites and the traditional Catalan song El Cant dels Ocells. On other nights we heard Sol Gabetta, sonorous and pliant in an exquisitely rendered Chopin Grand

Duo Concertante with pianist Kevin Fitz-Gerald; Gabetta’s mentor Geringas in a visionary reading of Schnittke’s Sonata no.1 with pianist Rina Dokshitsky; and Maisky’s powerfully expressive account of Britten’s Sonata in C major penned by the composer for his friend Rostropovich – another of Maisky’s teachers.

Some of the most enlightening moments of the festival were to be found among the twelve masterclasses. For the student fellows – many of whom have won competition prizes and have already embarked on their careers – these open lessons with artists including Mørk, Queyras, Carr, Lesser, Ronald Leonard, Frans Helmerson and Jens Peter Maintz will have been of invaluable and lasting benefit. From the spectators’ viewpoint, observing how these cello masters separate out the elements of key areas of repertoire and zone in on areas for consideration, offered an absorbing window into how their interpretative minds work.

‘He’s telling something that refers to music hundreds of years ago, so the sound should be like a memory from the past,’ Mørk explains to Zlatomir Fung, a student of Richard Aaron and Julie Albers, referring to the fuga movement in Britten’s Cello Suite no.1. ‘You have observed all the markings, but with the middle part you need to tap into the rhythmic drive and precision.’ Fung begins the fugue again, and immediately a more vibrant and confident version begins to emerge.

‘Piatigorsky believed profoundly in playing the cello as a means of expression – speaking and singing through the instrument while telling a meaningful and characterful story,’ says Kirshbaum. This belief informs everything Kirshbaum has set out to achieve with this festival, and it is his hope that the young artists – in whose hands the future of the instrument rests – will continue to explore and enjoy the cello and its repertoire as Piatigorsky did. ‘For me, that’s what this is about: the opportunity to encourage a lasting passion and motivation for music.’

ANNA CLYNE: COMPOSING FOR 100 CELLOS

The British composer explains the inspiration behind Threads & Traces for mass cello ensemble

As part of the Piatigorsky Cello Festival I was commissioned to write a work for a hundred cellos, to be divided between four to eight parts, with multiple cellists playing each part. It was to be paired on the programme with Villa-Lobos’s colourful and raucous Bachianas Brasileiras no.1, which has the cellists playing at full throttle. I therefore decided to explore timbral effects and textures at the opposite end of the spectrum – a very soft and delicately woven sound world.

In the end I divided the resulting piece, Threads & Traces, into eight parts, but I still wanted to explore interesting ways to take full advantage of the massed cellists, so I created divisi within each part. For example, one melodic line would be coloured by playing the same line with multiple different techniques – half of the cellists playing molto sul ponticello (very close to the bridge) to create a distorted electronic-like sound, while the other half played molto sul tasto (high up on the fingerboard) to create a very soft, flute-like sonority, for instance. The two played simultaneously, creating an interesting sound that was only possible with the mass ensemble.

As a rusty cellist, I found that one of the most enjoyable outcomes of the compositional process was that it gave me a reason to get back to playing the cello on a daily basis. I would play through all the parts and explore the possible placements of harmonics, or bowing patterns for the more modal melodic material. The score is highly detailed, to create a uniform sound within the ensemble. One of the reasons why I was originally drawn to the sound of the cello – in addition to its gorgeously resonant sonority – is that it has a range that spans that of the human voice, from bass to soprano. This is something I also explored in my piece. For much of the work the cellists play without vibrato to create a softer sound, like early music – the vibrato being saved for just a few moments of expressive contours within the melodic lines.

From the July 2016 issue of The Strad. Click here to subscribe

SAKURA AND SOLLIMA PHOTOS DANIEL ANDERSON/USC. CELLO ENSEMBLE DARIO GRIFFIN/USC

No comments yet