Learn to question received wisdom and keep an open mind, says the acclaimed Baroque violinist

Rachel Podger. Photo: Theresa Pewal

I was born in England but my mother is from Hamburg, and we moved to Germany when I was still young. Although both my parents are very musical, I didn’t quite have the traditional string-player childhood. Music at home was more likely to involve singing some Buxtehude and playing some Sweelinck, or the like. There were a lot of trio sonatas, too, with me on the second part as my older brother Julian was still the more advanced violinist. In one slow movement, I remember that my first note was so long I didn’t know how to count it. My father, who has the patience of a saint, wrote on the beats and showed me how it worked in relation to the bass-line, which my mother was playing on the cello. It was one of those moments when all of a sudden something becomes absolutely clear.

I had quite a Russian-inspired teacher when I was at school who was keen for me to take part in competitions and win some prizes, but my parents never pushed me in that direction. They were more interested in making music together than in any of us excelling as an individual, which is an approach I’m very grateful to them for. I remember my brother listening to me try to make my tone as big as possible in some Saint-Saëns, and complaining that the music was all ‘me, me, me!’

Although I never would have let him think he was right, it made me listen slightly differently to what my teachers had to say. One of them gave me his copy of solo Bach and asked me to transfer the markings into my own copy in pen. At home, biro hovering above the page, I saw that he had marked an up bow on the first down-beat of the B minor Partita. That seemed odd to me, so in our next lesson, I checked it was really what he meant. He bristled, narrowed his eyes and said, ‘you have been infected!’ He was very polite for the remainder of the lesson, but afterwards he called my parents and suggested they find someone else to teach me.

The Baroque violin still seemed quite alien to lots of people when I was at music college in the early 1990s, but my teacher David Takeno was wonderfully open-minded. As I came into his room, he’d ask me, ‘So what is it today then? Pre-chin rest or post-chin rest?’ I’d take out all sorts of weird 17th-century repertoire he might not have heard of but he knew exactly which questions to ask to help me understand it better. This was all the encouragement I needed to go out and scour libraries for manuscripts and music I hadn’t seen before.

David was – and still is – an excellent source of advice. Something he said to me that I use now with my own students is that if there’s something preoccupying you, or you’re a bit tired or, for whatever reason, you aren’t looking forward to playing, put it to one side before you step out in front of the audience. The motto was ‘leave your life at the stage door’. If you do, you’re light and liberated and free to express yourself. It sounds simple but it really works.

-

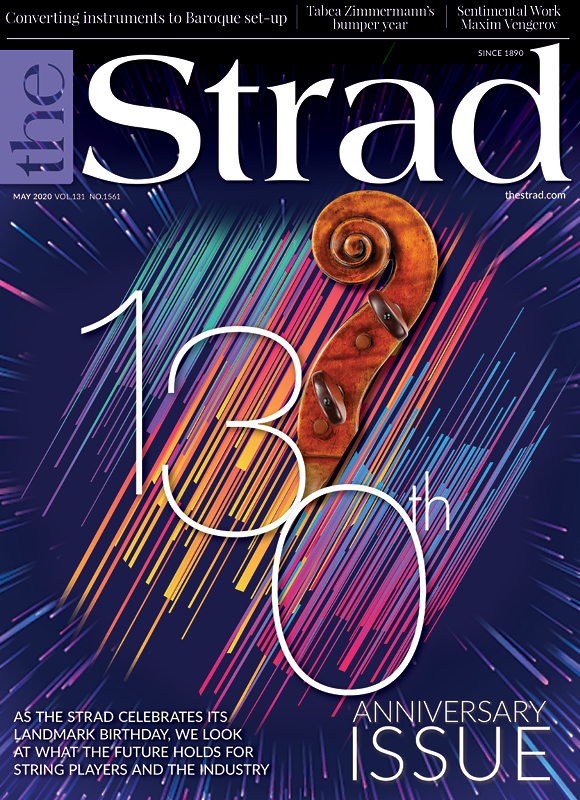

This article was published in the May 2020 130th Anniversary issue

The Strad marks its 130th anniversary with a look at the future of string playing and the violin industry. Explore all the articles in this issue.

More from this issue…

- A look at the future of string playing and the industry

- Violist Tabea Zimmermann on her bumper year

- Converting an instrument to Baroque set-up

- Making a career in music therapy

- How luthiers can avoid repetitive strain injury

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet