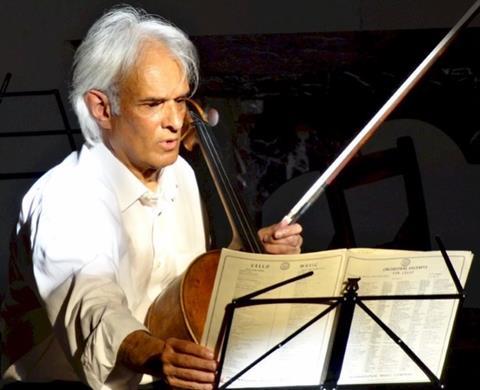

The former cellist of the Arditti Quartet on his journey from the 19th to the 20th century, and returning to his childhood studies of traditional Sri Lankan drumming

My life has been a mix of cultures from the start. I was born in the UK but my family returned home the same year to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), a country that had been colonised by the Portuguese, Dutch and British. We spoke Sinhalese and English, ate eastern and western food, studied traditional Kandyan drumming and had piano lessons. My parents were keen amateur musicians and hoped one of their four children would learn another instrument so we could play chamber music at home. It so happened that Martin Hohermann, a refugee from Warsaw who played the cello in a band in Colombo, heard me play the piano at a children’s concert. Although initially reluctant to teach a child my age, he decided he’d teach me the cello. He soon became insistent that I should become a musician, against my parents’ wishes, but after accepting his advice, my mother brought me, aged ten years old, to Europe to audition. Gaspar Cassadó offered to teach me in Florence and at the Accademia Musicale Chigiana in Siena.

At the age of sixteen I became the first winner of the Suggia Award, enabling me to study with Pablo Casals in Puerto Rico, John Barbirolli in the UK, and at London’s Royal Academy of Music. I’d been largely self-taught in things other than music since the age of ten, and the award also paid for me to study some other subjects at Oxford University. Two elderly sisters, Helena and Margaret Deneke, invited me to stay at their home in Oxford. Margaret had been taught the piano by the youngest daughter of Robert and Clara Schumann, and life with the Denekes was an almost 19th-century sort of existence, but the time came for me to leave Oxford behind and step out into the 20th. To make ends meet, I worked as warden of the Sri Lankan Students’ Centre in London, while continuing to perform both solo and chamber repertoire. A big development in my life came when an adventurous producer at Hilversum Radio invited me to perform Nomos Alpha, a work for solo cello by Iannis Xenakis. It involved learning different techniques and opened up a new world to me. Soon after, in 1977, Irvine Arditti asked me to join his quartet where we worked together for many years with all the major composers of that generation.

Read: Nobuko Imai: Life Lessons

Read: Guy Johnston: Life Lessons

Read: Patricia Kopatchinskaja: Life Lessons

The Covid-19 lockdown has given me the chance to pursue my studies of the Kandyan drum rhythms of Sri Lanka. Luciano Berio asked me to notate a selection of these rhythms which he incorporated into his final Sequenza, which he dedicated to me. Since the end of the 18th century, both music and life in general have largely been preoccupied with the expression of the individual. Kandyan drummers and dancers, on the other hand, dedicate their music to the divine.

Interview by Tom Stewart

-

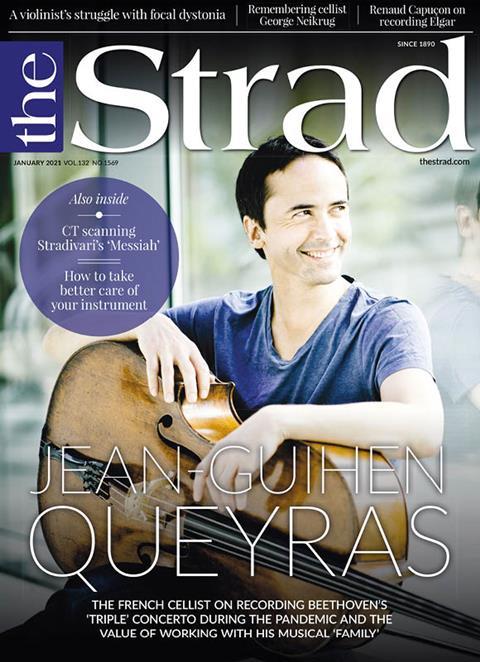

This article was published in the January 2021 Jean-Guihen Queyras issue

The French cellist on recording Beethoven’s ‘Triple’ Concerto during the pandemic and the value of working with his musical ‘family’. Explore all the articles in this issue. Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- French cellist Jean-Guihen Queyras

- CT scanning Stradivari’s ‘Messiah’

- Remembering cello tutor George Neikrug

- Renaud Capuçon on recording Elgar’s Violin Concerto

- How players can take better care of their instrument

- Playing Tchaikovsky with just two left-hand fingers

Read more playing content here

No comments yet