For the former leader of the Guarneri Quartet, Schubert’s Fantasy in C major is one of the most life-affirming works in the repertoire, as well as a test of technical skill

If I ever had to be marooned on a desert island, Schubert’s Fantasy in C major would be coming with me. For me, listening to it for those 25 minutes is like understanding the meaning of life and the mysteries of the universe. Schubert wrote a number of monumental works towards the end of his life, and I’m very grateful that one of them was for violin and piano – even though it’s one of the hardest in the repertoire, for both players!

I first heard it when I was in my twenties, soon after graduating from Curtis. I knew his song ‘Sei mir gegrüsst’, and wanted to hear how he’d made it into a theme and variations in the Fantasy’s second movement. The original song is much more innocent-sounding, whereas in the Fantasy it has an uplifting feeling, with elements of longing and a tinge of optimism. I’d found the 1931 recording by Adolf Busch and Rudolf Serkin, which knocked me off my feet – it was so deeply serious and filled with meaning that I didn’t dare play it myself for a long time.

When I did start practising it, I was thrilled to be discovering a work with so much substance. It’s a piece that unveils more depths of meaning with every performance. From the outset, the piano creates an air of mystery and expectation, followed by one long sustained note on the violin that enters out of nowhere, so subtle that you’re not sure if it’s really there. The majestic theme that comes out of that first movement is filled with longing, hope and a reaffirming sense of life itself. Then there’s the spectacular evolution of the variations, showing so many facets of music which are a huge challenge, partly because they’re fiendishly difficult and also because there’s a magnificent story running through them. It’s easy for each variation to stand alone, but to capture the narrative thread through them is the real challenge. Then there’s a transitional section as the variations come to an end, when it sounds like it’s moving towards a tragic resolution, but the third movement ends thrillingly. In some odd way the Fantasy reminds me of Beethoven’s Grosse Fuge whose at times chaotic nature nonetheless ends in a triumphant affirmation of life. It’s dangerous to try to apply emotional meaning to music but it seems as though Schubert, in the penultimate year of his life, was adding in moments of thought and reflection, culminating in this final burst of optimism.

I’ve performed the Fantasy many times, firstly with my brother Victor on the piano. I performed all Schubert’s violin and piano works with Seymour Lipkin on the piano, and eventually we made a recording of them together in 2006. I once gave a recital with the pianist Barbara Lister-Sink, who wanted to do something a little unusual: she had one of her students take over the piano part while she stood up and sang ‘Sei mir gegrüsst’, so the audience could get an idea of the inspiration behind the theme and variations. Then she sat back down and the student became her page turner as we performed the Fantasy together.

When you’re practising the Fantasy, don’t worry about its technical difficulties, but try to get a feeling for the work as a whole. I don’t usually advise students to listen to recordings, but in this case it’s useful to get a sense of the scope of the piece. Having a read-through session with the pianist is always useful too. If you keep an eye on the substance of the Fantasy, the technique tends to follow more easily.

Read: Sentimental Work: François Rabbath

Read: Sentimental Work: Jeffrey Solow

-

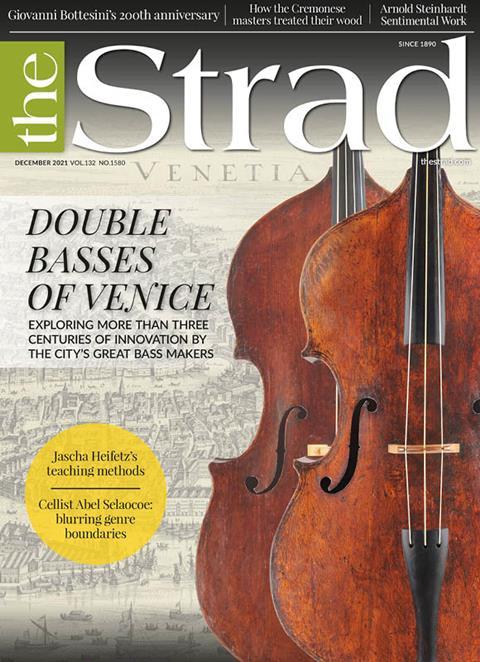

This article was published in the December 2021 ‘Double Basses of Venice’ issue

The north Italian city-state produced some of the country’s finest instruments . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- The Venetian double bass

- Celebrating Bottesini’s 200th anniversary

- South African cellist, composer and vocalist Abel Selaocoe

- Wood treatment on Cremonese instruments

- Heifetz as a teacher

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet