Whether you are an historically informed professional or just looking to expand your knowledge, we’ve pulled some interesting articles out of our archive just for you.

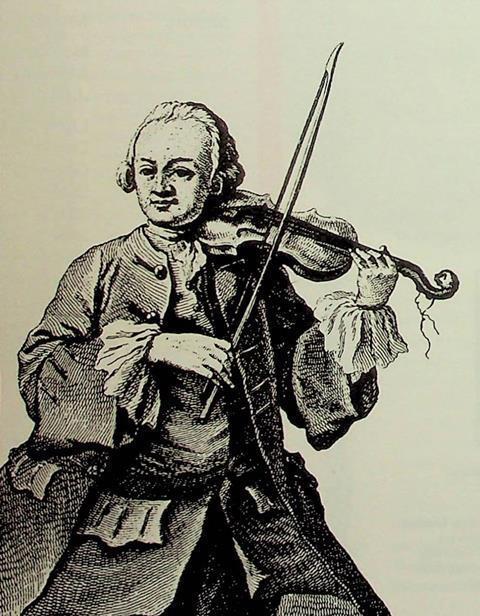

From Leopold Mozart’s Treatise on the Fundamental Principles of Violin Playing

From Leopold Mozart’s Treatise on the Fundamental Principles of Violin Playing

’”How wonderful… you mean Vivaldi and… er…” A frequent response to my confessing that I play the Baroque violin’

The names of many of the Baroque composers I most revere do not even appear in the old 1920s edition of Grove’s Dictionary slumbering in my local library, for their music lay on dusty shelves in church and court archives or in state libraries until the Baroque revivalists lovingly gathered it up and set it free to move and inspire us once more. How much astonishing variety there is: a century and a half of rich repertoire, sacred and profane, spiritual and uplifting, from the Venice of Monteverdi to the Vienna of Mozart via the Versailles of Mondonville (‘Who?’), with styles shifting from decade to decade and from city to city – not to mention ‘world Baroque’, such as the music of the Chiquitos, who composed Baroque-style Masses deep in the Bolivian jungle until the late 1800s, without even realising that Beethoven had come and gone!

Baroque violin professor Walter S. Reiter, who teaches Baroque Violin and Viola in the Royal Conservatory of The Hague and at Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance in London makes the case that historically informed performance requires no secret code. The information is out there for the taking, and modern music colleges need to get ahead of the game.

‘Keep it simple, stupid’

Recording a CD requires a lot of willpower, combined with superhuman endurance. Usually it takes about three days, approximately a three-hour session for each 15 minutes of music to record. Self-criticism is real, harsh, and it can be demoralising because you are dissecting your sound, your breath, your own musical sensitivity. But with Sir Roger it’s fun, dare I say almost easy! Suddenly everything makes sense, the direction that I have been seeking tenaciously for years is reborn, spontaneous and fresh, thanks to his ability to convey and relate with naturalness his encyclopaedic knowledge of classical performance practice and the history behind and inside each note. He summarises this in what he calls the six ’S’s’: Sources, Size, Seating, Speed, Sound, and Style.

Violinist Francesca Dego shares her experiences of collaborating with Sir Roger Norrington and how the six ‘S’s’ helped inform her new album of Mozart concertos.

’Our hope is to honour the spirit of the music and to get as close as possible to the intimacy of a 19th century chamber music performance’

Gut strings have a warm and special sound with so many colours to explore and incredible blending capacity. The sound is imperfect, in some ways dirtier than the brilliance of metal strings, but in a way that allows you to really characterise the music. It feels honest and visceral, but then you also have to know how far you can push the sound. With gut strings, the player is forced to work harder to really draw the sound from the string and with the rougher texture of the sheep gut, you really feel the connection between notes when shifting. It is a very physical process.

However, playing on gut strings presents a great many challenges. They are particularly sensitive to changes in the environment such as temperature and humidity, so tuning and squeaking can be problematic! Because of this, we feel that we can’t be so fixed in our interpretations, and instead we work in rehearsals to find as much freedom as possible.

The Consone Quartet explains why all players should feel able to dip a toe into historically informed performance.

’You will trust a good bow immediately, and never want to play Baroque music with a modern one again’

Baroque bows play differently from modern bows; they can teach the musician new ways of articulation and reveal fresh possibilities in the music. But the average factory worker doesn’t know this and will never have seen or played an actual 18th-century bow, and neither will their bosses. This differs from their production of modern bows, which are readily available for sale in every shop in the world. Most makers of Baroque bows sell on their own, not through dealers.

Most people in your position will buy a bow to fit all kinds of Baroque music – a kind of mid-18th-century model with an adjuster. Often these can be a compromised design aimed at players new to Baroque playing; they may be pretty, but sometimes this kind of heavier bow can feel sluggish. It may offer a feeling of familiarity for the modern player, but that’s just plain lazy and I think you must be challenged.

Luthiers from around the globe take a moment to answer some of our most pressing questions when it comes to the world of the Baroque Bow.

’Put a set of gut strings on your cello, borrow a Baroque bow and have a go!’

Relatively few modern string players have taken an interest in Baroque instruments and the performance practices associated with them. I play both Baroque and modern cello professionally and I can say that my involvement with the Baroque has a constant influence on my approach to later repertoire, it can be hard work to maintain a technique on both sets of instruments but the rewards are enormous.

Cellist Daniel Yeadon argues you don’t need years of study to play Baroque cello with style and panache, just a willingness to think differently. Exploring metal versus gut, the bow and the freeing yet tricky lack of spike, Yeadon compares the two instruments that have had a profound influence on each other in his playing.

No comments yet