The artistic leader of the Ševčík Academy gives his perspectives on the renowned exercises

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

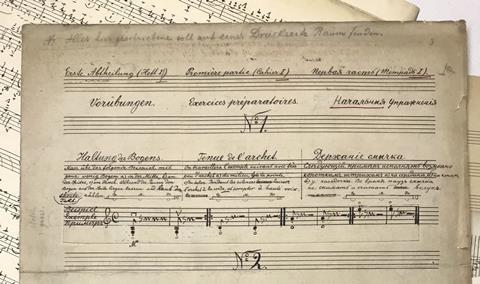

Perhaps every string player has come across Otakar Ševčík’s exercises at least once. However, few have any idea how complex an instrumental school it is. Five years ago, we founded the Otakar Ševčík Institute and the Ševčík Academy in the Czech Republic - institutions that are gradually trying to reconstruct the entire Ševčík Method. Much good has been written about the Ševčík Method; here are five ideas that may provide a new perspective.

1) All the parts of the Ševčík Method form a whole

Otakar Ševčík wrote his exercises initially for himself, as he sought to improve his playing. During his time at the Kiev Conservatory he completed his first two seminal opuses for left and right hand technique. Gradually he added more works, which began to form a body of work covering the range from beginners to virtuoso players. The whole method is aptly summarised in a table by Victor Nopp, a student of Ševčík’s, which shows the thoughtfulness and continuity of the exercises.

At the Prague Conservatory, the Ševčík Method was gradually introduced as the main methodological material for violin playing. The same was true in other cities; for example, in 1932, after a visit by Ševčík, his method was adopted as the main teaching material at the Boston Conservatory. Ševčík also taught according to his comprehensive method in his peak years, 1909-1919, at the University of the Arts in Vienna.

2) There are unknown parts of Ševčík’s method

Even though the method is incredibly extensive, some parts are still missing. In 1921, Ševčík submitted a manuscript of four works to a publisher in New York, for which he was paid but never published. These were four works of the so-called ’virtuoso school’, which dealt with the technique of double stops, arpeggios, modulations, chords, harmonics and pizzicato.

Also remaining in the manuscript are materials that Ševčík wrote for his ’foreign colony’. These are parts of his method or arrangements of pieces for violin orchestra. What is also missing is any connecting piece that would allow the method to be used in its entirety. When a student asked Otakar Ševčík why he did not write such a text part for his method, Ševčík jokingly replied: because no student would read it!

3) Ševčík’s method comprises a linguistic philsophy

The main idea of the whole method is not so much musical as mathematical and linguistic. Ševčík works with intonation and interpretation as the meaning of the word, and with violin technique as the word itself. He was inspired by books he found in the library of his father Josef Ševčík, a cantor at the local school in Horažďovice. One of the books described a method of teaching by thoughtful repetition of words and phrases, but always with a precise awareness of the meaning of the word and the meaning of the sentence.

Thanks to his innovative approach to violin teaching, Ševčík succeeded in distilling technical problems that could be worked on separately. This repetitive aspect may be behind why Ševčík has sometimes been accused of ’factory-producing virtuoso players’. It is true that Ševčík’s best students practised no less than six hours a day, some as many as ten, and the record was said to be thirteen. But Ševčík did not train his students to be technically equipped robots, but players free from technical difficulties. He believed that with the step onto the stage, there was no need to think about technique, but to let the soul of the player speak.

Read: 6 tips for practising fast passages: violinist Susanna Klein

Read: The Suzuki approach to tone: Every tone has a living soul – Shinichi Suzuki

4) Practice ideally in pairs

Ševčík almost always used piano or second violin accompaniment in his teaching. He was of the opinion that when a chord is struck in the piano, the sound of the violin ’bounces’ and the player intuitively seeks the correct finger position. When playing with a second violin, there is a danger that the nature of the sound is too similar and does not force the player to intonate accurately. Only as a last option is practising the piece without the accompaniment of any instrument.

In this perspective, it seems logical that Ševčík developed second violin parts for violin concertos, such as Wieniawski’s Violin Concerto no. 2. It is therefore possible that Otakar Ševčík could have accompanied Henrietta Claudine Wieniawski, his pupil and daughter of the composer himself, on the violin!

5) Folk music is important to musical development

Ševčík believed that folk music was important for the development of musicianship. He stated that if a student played a melody he could sing, he would be better at phrasing and intonation. In an interview with the American magazine The Etude in 1924, Ševčík stated, ’The reason that the Russian and Jewish violinists have a so uniformly good tone, and a fine vibrato, is that from the earliest years they hear much good singing in their homes and in the rituals of their religions. They learn to hear and think good tones and therefore they express good tones when they later learn the violin.’

Czech folk songs are integrated into both the School for Beginners op. 6 and the School of Intonation Op. 11. The latter contains 40 duets for two violins, small Czech folk songs that are a joy to play.

Folk music is the theme of the fifth edition of the Ševčík Academy and Festival, which will take place in Horažďovice from 6-18 August 2023. The deadline for applications is 31 May, you can apply here.

Watch: ‘We never forget to have fun’ - Violist Allan Nilles on the Ševčík Academy

Read: Professor Ševčík addresses Strad readers

Read more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

This year’s calendar celebrates the top instruments played by members of the Australian Chamber Orchestra, Melbourne Symphony, Australian String Quartet and some of the country’s greatest soloists.

No comments yet