The Israeli–American cellist talks about body awareness and the importance of taking the initiative

I started learning the cello quite late, at ten years old, so I had to understand playing from an intellectual point of view rather than through imitation. I was lucky that my first two teachers – Csaba Balok, who was also a yoga teacher, and Uri Vardi – were both students of János Starker, who was known for encouraging body awareness in playing. Through them I learnt how to use my breathing, weight and movement to express myself musically. Uri liked to say, ‘Your body is your Strad.’ I feel very thankful for having that instilled in me from day one. My whole being as a cellist today is based on those years. Your priority is to express music in the best way you can, and to do this you must know that you’re making music with your body.

My first big obstacle as a young musician was being drafted into the Israeli army. Although I was picked for its string quartet, I couldn’t play for the three weeks of basic training. It was the first time in my life that I hadn’t played cello for so long and I was scared of what would happen. When I came back I played the Kodály Sonata, and my teacher Shmuel Magen said, ‘You see, you didn’t forget anything!’ It was a valuable realisation.

Another important experience was when I arrived at Yale. Coming from a place where I was one of the best players, I was now one of many. It took me a while not to be depressed by it, but instead to learn from it and push myself harder.

Two pieces of advice stay with me today. Firstly, my dear teacher Bernard Greenhouse said, ‘You are judged by your voice, not how loud or fast you play.’ What is your sound? How will people recognise it? These are important questions for young musicians to ask themselves. Secondly, Laurence Lesser, my teacher at the New England Conservatory, told me in my last lesson: ‘Amit, you have a place in this industry, but nobody needs you. Find it yourself.’ As hurtful as this was, it made me realise the importance of initiative. I feel that all the things that have happened to me have happened because of me. When you see an exit on the highway, be curious enough to take it.

We should open our eyes and ears to where we live and play for small communities. You can do just as much good playing in schools, retirement homes and jails as you can in Carnegie Hall. It is unbelievable how music can impact people. During the pandemic I started an online cello academy, with students from all over the world. As an Israeli, it was touching to be able to teach cellists from places like Saudi Arabia and Syria, for example. Now with technology, we can use music to overcome financial, political and visa issues. The musical world really is a small village.

INTERVIEW BY RITA FERNANDES

-

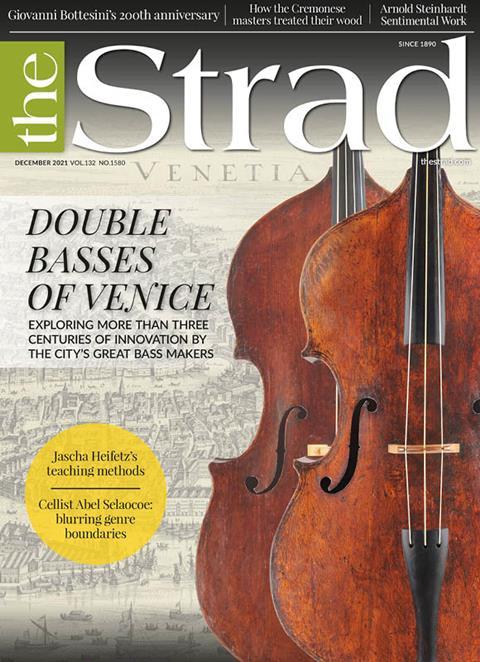

This article was published in the December 2021 ‘Double Basses of Venice’ issue

The north Italian city-state produced some of the country’s finest instruments . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- The Venetian double bass

- Celebrating Bottesini’s 200th anniversary

- South African cellist, composer and vocalist Abel Selaocoe

- Wood treatment on Cremonese instruments

- Heifetz as a teacher

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet