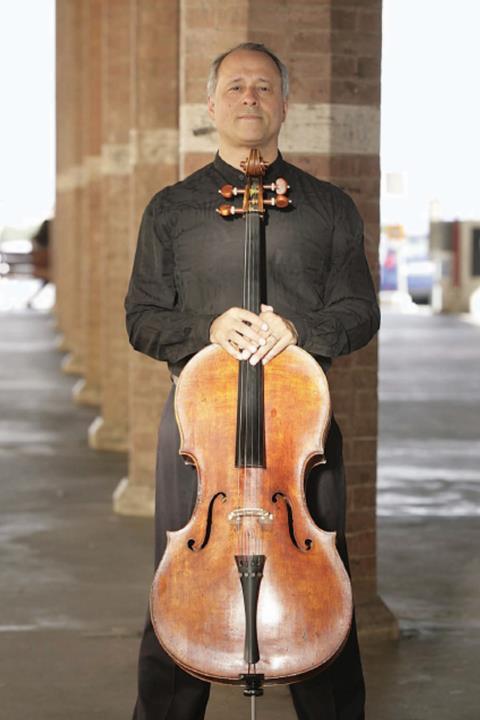

Cellist Antonio Meneses featured as the cover artist for The Strad’s August 2012 issue. Despite an uncompromising introduction to the instrument, the Brazilian cellist went on to excel in Classical and Romantic repertoire. He explained to Nick Shave why he then began exploring lesser-known works

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub.

Read more premium content for subscribers here

When Antonio Meneses won first prize in the Tchaikovsky Competition in 1982, its contestants were expected to perform, among other works, a Haydn concerto movement, Bach’s Cello Suite no.4, and the Dvořák Concerto – cornerstones of the cello repertoire, and precisely the kind of pieces with which Meneses felt most at home. Since then, the Brazilian has established himself in traditional repertoire, recording the Bach suites, the Brahms ‘Double’ Concerto (with Anne-Sophie Mutter), and the Haydn, Schubert and Schumann concertos. It’s in the Classical and Romantic traditions that Meneses seems to thrive, both as a soloist and in his chamber playing with the Beaux Arts Trio.

But it’s from this platform of core works that the cellist also dives into less familiar waters: Baroque repertoire with Carlo Graziani’s Six Sonatas op.3; 20th-century works for cello and orchestra by another rarely explored Italian composer, Giorgio Federico Ghedini; and new commissions, such as the Double Cello Concerto by Swiss composer Fabian Müller, which Meneses premiered with fellow cellist Pi-Chin Chien in Bangkok last year. As well as being a Romanticist who flourishes in Beethoven and Brahms, Meneses also shows an ever-expanding curiosity, and a desire to champion rarely performed works – nowhere more so than in his latest project, the world-premiere recording of Hans Gál’s Cello Concerto with the UK’s Northern Sinfonia.

At first glance, this might seem like a high-risk venture. The 1944 work, which was recommended to Meneses by his producer Simon Fox Gál (the Viennese composer’s grandson), has always had a rather low-key presence among cello concertos. Stylistically, the Gál Concerto has more in common with the 19th century than with the Second Viennese School, or indeed any other music of the Second World War years. It is conceived in three movements and has moments of immense lyricism, nostalgia and melancholy, not unlike the popular Elgar Concerto with which Meneses has thoughtfully – and wisely, perhaps – coupled it on disc.

Besides lending the Gál Concerto gravitas, the pairing of these two anachronistic works hints at interesting biographical parallels between their composers. Just as Elgar wrote his Concerto in the aftermath of the First World War, revealing his disillusionment by using a starker, more direct tone than that of his previous works, so the Jewish Gál wrote his following a period of tragic upheaval in his life. Fleeing the Nazi invasion of Vienna, Gál emigrated to England with his family in 1938, where he was imprisoned as an enemy alien. Family members that he left behind either died or committed suicide to avoid deportation to the concentration camps.

‘I like to see what I can get out of the score itself, rather than try to make too many connections with the composer’s life’

Yet where Elgar plunders the depths of despair, Gál finds musical colour and light, and even humour in the final movement – a refuge, perhaps, from the dark realities of his life. ‘It happens so often that composers who are living through a difficult time will write happy music,’ explains Meneses. ‘But you can’t approach Gál through his biography because it’s not like we know so much about his life. I am more the kind of person who likes to see what I can get out of the score itself, rather than try to make too many connections with what is going on in the composer’s life.’

Technically, Gál’s Concerto throws up greater challenges than the Elgar does – which is less a result of virtuosic fingerwork, and more simply down to the high register to which its cello line often seems to levitate. Meneses compares the Gál with another work he has recorded, the Haydn Cello Concerto no.2 – one of the most difficult works in the cello repertoire. ‘The Haydn has one thing that makes it easier: it’s in D major, so you can get around the instrument, from low to high – and the harmonics in the middle of the instrument give you a sense of positioning. On the other hand, the Gál is written in unusual keys that don’t give you this facility, and you have to create in your mind where these positions are.’ And then there’s Gál’s language – the give and take between cello and woodwind. ‘I needed some time to get into the feeling of his music, because it’s very chamber music-like, in the sense that all the woodwind instruments have important statements. You have to work hard to integrate the cello part within those statements.’

INSTRUMENTS

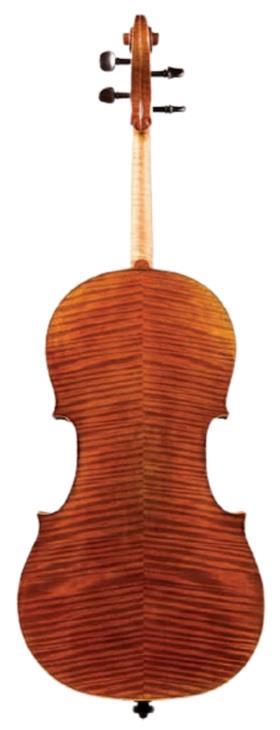

Meneses owns two cellos, the most important of which is his c.1730 Alessandro Gagliano. He bought it eight years ago from his friend and fellow cellist Thomas Demenga. ‘I had known the instrument for a long time, because he had owned it for 20 years,’ says Meneses. ‘I love its sound quality.’

Deep and resonant in the bass, and with a bright sound in the upper register that can easily cut through an orchestra, the Gagliano is ideal for playing concertos. Its main weakness is its size: it is longer than usual, making it slightly harder to play. ‘I have big hands, but even for me it presents difficulties,’ says Meneses.

To avoid buying a ticket for his cello every time he travels to Brazil, Meneses keeps a modern copy of a Stradivari there, built by Swissbased maker Michael Stürzenhofecker in 2009. It has a stronger bass than the Gagliano, and can produce a beautifully expressive tone. ‘But its sound has been altered by the humidity, so I haven’t played it recently,’ Meneses explains.

It helps, of course, that Meneses was exposed to the Romantic tradition from an early age. Born in Recife, northeast Brazil, he grew up in a musical family: his father, first horn at the Rio de Janeiro Opera House, would take him to performances, giving the young Antonio his first taste of La traviata and Madama Butterfly, and of Bach’s cello suite arranged for horn. But when it came to Meneses choosing an instrument – or indeed deciding whether he even wanted to study music – he had little say. After noticing that there was a dearth of string players in the local orchestra, his father resolved to train Antonio (and subsequently his four younger brothers) on stringed instruments. ‘He bought me a cello when I was ten years old and said, “From now on you play the cello. I already have a teacher for you, so next week you start your own lessons,”’ recalls Meneses.

His four brothers – three violinists and one cellist – all went on to professional careers at the Rio de Janeiro Opera House. Meneses began playing professionally with the Brazilian Symphony Orchestra (BSO) when he was only 14, shuttling between school lessons and orchestra rehearsals, but his career took a different path after cellist Antonio Janigro, on tour with the BSO, heard him play. ‘He liked my talent, but he thought my way of playing was a disaster,’ Meneses recalls. They agreed that he would travel to Düsseldorf to study with Janigro. ‘It was a huge step, especially for someone like me. I didn’t know any German, any English or any other language, and it was frightening at the beginning. But I felt a spark of ambition to improve.’

It was during these formative years, too, that Meneses first heard Jacqueline du Pré’s recording of the Elgar Concerto. It took some time before he could free himself from her influence. ‘Whether you want it to or not, I don’t think you can avoid it making a certain impact. You have to get the original score and work out exactly what you think is important in that piece,’ he says now. In his recording, Meneses closely observes Elgar’s tempo markings, taking the closing Adagio more quickly than many players, du Pré included. ‘In the end I have found the piece is much less full of pathos than generally thought. The conclusion of the last movement can be endless if you don’t know how to pace it well. I have the feeling that Elgar is always asking you to play it slower and slower and still slower, but it’s not really true: there must be a sense of continuation of the line. If you are not able to do that, the piece falls apart.’

As well as a deep musical intuition and a shrewdly analytical approach to the scores he plays, competition have stood Meneses in good stead. He won second prize in Barcelona’s Maria Canals competition in his teens, before entering the prestigious ARD Munich competition when he was 20. At the time, Janigro was ill and unable to teach, so Meneses took it upon himself to learn the competition repertoire on his own – and won. ‘The main thing I remember about winning is that I got some money – 6,000 German marks, which for me was an unbelievable fortune.’ His first purchase was a winter coat – not something he’d needed in Rio, but something he had sorely missed during the European winters. The prize attracted concert invitations, too, and Meneses began to take on the concerto repertoire, playing the Schumann with Wolfgang Sawallisch and fi nding managers in both Brazil and Germany. ‘All of a sudden I had concerts,’ he says.

It was a risk, then, when five years later – with his career in full flow – Meneses entered the Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow. ‘Janigro advised me not to compete because if I lost, it would not be good for my career.’ But nevertheless, Meneses entered and won, opening yet more doors: he was invited to play with the Berlin Philharmonic under Karajan (‘Most of the time he was very nice, but he could also get very impatient’) and toured – in Australia and Japan with the Czech Philharmonic. But asked whether music contests still have the power to transform careers, Meneses sounds doubtful. ‘I have mixed feelings, because there are so many competitions, and there are very many young musicians who are able to win these competitions, but the market for new violinists and cellists is not that much bigger. Very often I see young musicians putting all their hopes into these competitions and discovering that they don’t help as much as they used to.’

These days, Meneses is based in Bern, Switzerland, where he teaches at the university. He also gives masterclasses around Europe and teaches at Siena’s Accademia Musicale Chigiana every summer. But since leaving Brazil at the age of 16, he has maintained close ties with Rio de Janeiro, returning every year to see his family, and performing with the BSO. When in 2011 the orchestra’s artistic director Roberto Minczuk called on his players to re-audition for their jobs, Meneses wrote an open letter to the São Paulo newspapers expressing his distress at the way in which the musicians – many of them his friends since childhood – were being treated, and calling for a diplomatic solution to the crisis. ‘In any orchestra in the world, you cannot ask regular musicians, who have auditioned to get there, to audition again,’ he explains. Minczuk later stepped down as director, and the situation was resolved months afterwards, with dismissed musicians being reinstated to create a new orchestra. Meneses has not been invited to play with them, but he stands by his action. ‘I have the feeling it made some impact,’ he says. ‘Those who were involved thanked me for it.’

He’s also become more closely involved with the new-music scene in Brazil. After recording the Bach cello suites in 2004, Meneses commissioned a prelude for each of them from six Brazilian composers, and has since commissioned one of the composers, Marco Padilha, to write him a cello concerto, which he’ll premiere this November with the São Paulo State Symphony Orchestra. ‘When I see great musicians of our times who are interested in modern music, they have always tried to help the composers of their own time and own country. I felt a bit guilty about the fact I had neglected my contact with composers, and at the same time I felt a kind of need for it.’ So what took him so long? ‘I was so involved in the more usual cello repertoire, first of all. And whenever there was an opportunity to play something new, it was mostly a piece from Europe.’

Not that Meneses will neglect the great European masters. As well as continuing his performances with Beaux Arts Trio pianist Menahem Pressler, with whom he has recorded Beethoven’s complete works for cello and piano, Meneses is now enjoying a flourishing collaboration with Portuguese pianist Maria João Pires, performing solo and duo works by Schubert, Brahms and Mendelssohn at London’s Wigmore Hall in January. ‘The most important thing for me now in terms of recordings is this relationship with Maria,’ he says. They’re planning more recitals, including Beethoven and Brahms sonatas as well as the Beethoven ‘Triple’ Concerto. ‘If I were a pianist I would never leave the 19th century: there is so much beautiful repertoire that it’s difficult to be interested in anything else.’

THE YOUNG MENESES

A review from the January 1984 issue of The Strad shows the cellist’s talents were already fully formed

Antonio Meneses (cello), Franz Massinger (piano)

Ambassador Auditorium, Los Angeles, 12 November 1983

The local debut of Antonio Meneses drew little more than a corporal’s guard. This was unfortunate, since the twenty six- year-old Brazilian proved to be one of those rare competition laureates who is not only a brilliant instrumentalist, but a true artist in every sense of the term.

There may be young cellists with more sheer opulence of tone or glittering heroic thrust. Meneses, however, boasts a veritable armoury of qualities that mark him as an extraordinary recitalist. Above all, he is a stylist, superbly sensitive to the character of the music he is performing, a tone colourist who diversifies his sound and vibrato with subtle mastery, and the possessor of a smouldering temperament that is firmly disciplined. Technically his intonation is immaculate, his facility dextrous.

For a warm-up he played Beethoven’s Seven Variations on the duet “Bei Männern, welche Liebe fühlen” from Mozart’s Magic Flute. The cellist delineated each variation intelligently, but it was not until he came to grips with the piquant Gallicisms of Debussy’s Sonata, which he endowed with a wealth of subtle nuances and kaleidoscopic gamut of dynamics, that the stature of his playing was fully verified.

Schubert’s “Arpeggione” Sonata contained some blandness of sound and over-reticence, though as an entity, it was solidly wrought. A scholarly, yet impassioned performance of Brahms’ Sonata No. 1 in E minor was occasionally vitiated by tonal raspiness.

HENRY ROTH

The Strad is offering customers the chance to purchase print magazines from its archives, while stocks last. Get your copy here before they’re all gone!

Read: Cellist Antonio Meneses on the unique qualities of his Luiz Amorim cello

Read: Three’s company: the rise of piano trios

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub.

Read more premium content for subscribers here

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

American collector David L. Fulton amassed one of the 20th century’s finest collections of stringed instruments. This year’s calendar pays tribute to some of these priceless treasures, including Yehudi Menuhin’s celebrated ‘Lord Wilton’ Guarneri, the Carlo Bergonzi once played by Fritz Kreisler, and four instruments by Antonio Stradivari.

No comments yet