In this extract from the August 2021 issue, professor of cello at the Juilliard School Timothy Eddy provides tips for students and teachers on building an emotional connection with music and harnessing technique to play with expression

The following extract is from The Strad’s August issue Technique feature ‘Playing with expression’. To read it in full, click here to subscribe and login. The August 2021 digital magazine and print edition are on sale now

IN YOUR PRACTICE

Beginning practice with scales, arpeggios and double-stops, letting the ear lead the left hand, will help you to establish accurate intonation and dependable reflexes. Etudes, with their musical structure, will then allow you to weave technical practice in with work on character and sound. Avoid stopping the flow of the music to deal with problems every time that they arise: your hands need to feel each phrase, not only sequences of small, local details.

If your technique prohibits you from communicating music as you feel it, try not to let frustration drive you into obsessive technical practice. Instead have patience, release physically, play something characterfully a few times and see if your technique catches on. Slow down places that need work, hear each note in your mind before you play and ask yourself if your feelings and personality are coming across clearly in your sound, as you communicate the emotional story that the composer has given to you through the evocative power of musical structure. Celebrate each note in terms of its beauty and excellence.

Read: ‘I value them as supremely sharp tools’ - Colin Carr on Popper studies

Read: Pedagogues’ top studies: Etude of choice

TIPS FOR TEACHERS

If students become too obsessed with accuracy and the near-perfection of technique and can’t let go enough to trust their reflexes and play from the heart, they can create a kind of prison for themselves. This type of technical accomplishment is valuable up to a point, but real musical energy should come from feeling, not from the mind. Sometimes I’ll stop a student and ask, ‘What were you caring about the most when you played that?’ Often they were caring about not making mistakes. I empathise: it’s a tough art. But the principal artistic aim is not to achieve technical ‘perfection’. It is to speak eloquently and generously, to share their hearts and souls.

Teachers can encourage students to develop a closer, more personal relationship with their music; to help them speak more naturally with their own emotions and voices. This, like most things, can be trained. The number one issue is to help our students access the vivid, volatile, rich emotional history and personality that everyone has within themselves, and to make that their primary resource as they play.

-

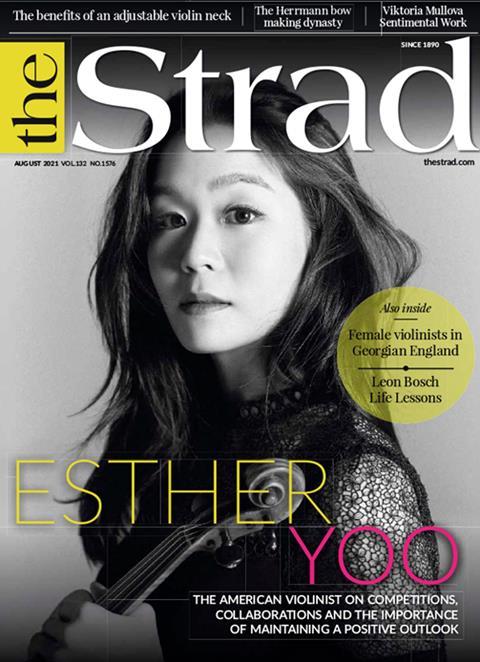

This article was published in the August 2021 Esther Yoo issue

The American violinist on competitions, collaborations and the importance of maintaining a positive outlook. Explore all the articles in this issue . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- American violinist Esther Yoo

- The benefits of an adjustable violin neck

- Bach’s Solo Violin Partitas

- The Herrmann bow making dynasty

- Female violinists in 18th-century England

- Making accurate arching templates

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet