Heifetz’s former personal accompanist Ayke Agus recalls the violinist’s incentives and methods for getting the best from his students, in this extract by Enrico Alvares

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

This article is an extract from The Strad’s December 2021 issue

’Well, if Heifetz had a method, it was probably the one he learnt from Auer,’ Agus says. ‘We all tend to emulate the teachers who made the biggest impact on us.’

She lists a number of comparisons and contrasts between the Auer and Heifetz methods:

- ‘Neither focused on technical matters, choosing instead to work on deepening their students’ interpretative skills and general musical understanding – although both were sticklers for technical accuracy as required for proper service to the music’

- ‘Auer didn’t demonstrate much whereas Heifetz demonstrated a great deal. The only downfall of these demonstrations was that the playing was so magical it was almost always impossible for the poor student to focus on whatever point was being demonstrated!’

- ‘Both Auer and Heifetz accepted no excuse for lack of discipline or for sloppiness. They both expected intelligent work habits and great attention to detail. The weekly lesson preparation was intentionally as gruelling as for a full recital performance’

- ‘While both pushed their students to their limits, they each also remained devoted to their students’ needs.’ (At this point we speak off the record of numerous acts of exceptional generosity on Heifetz’s part – almost none of which are public knowledge, at his insistence)

- ‘Both expected every violin student to be able to play the piano and the viola – no exceptions’

‘In Heifetz’s class,’ she continues, ‘every student had to be ready and prepared to play at any time the following from memory, whether or not it was their day for an individual lesson: all scales and arpeggios with all their variations, an etude, a solo Bach movement and an encore piece (an “itsy-bitsy”, as he called them).’

The class pianist, too, was expected to be fully prepared. ‘Whichever concerto was being worked on, Heifetz insisted the opening thematic idea had to be heard in full,’ remembers Agus. ‘The pianist had to be ready to play entire tutti sections from the beginning of the piece, with the correct orchestral colours.’ She recounts one memorable occasion when Heifetz spent 20 minutes honing five bars of the opening tutti of Bruch’s First Concerto before the student was allowed finally to enter with the opening solo. Only after the pianist had proved themselves were they allowed to use the usual tutti cuts.

‘Heifetz also insisted that students throw their solo parts into the bin and stick to studying from the piano accompaniment score,’ says Agus. ‘It’s for this reason that the violin line in the piano parts of genuine Heifetz transcriptions include all bowings and fingerings found in the solo part. On one occasion, a publisher’s proof arrived with Heifetz’s markings removed from the piano part’s violin line. The publisher explained it was not its standard policy to include such marks in the piano part – and was, of course, summarily dropped by Heifetz, who proceeded to find another.’

It may be surprising to hear, too, that pencils were not allowed on the music stand in class, according to Agus. ‘Don’t write it down. Remember it!’ was Heifetz’s admonition. ‘He believed in properly training the brain, rather than simply filling a piece of paper with memory aids. He felt that most people have a greater mental ability than they realise and that almost everyone has at least some aspect of a photographic memory, which could be developed with work,’ she says. In fact, the only words allowed to be written in a student’s part were Italian musical terms – no directions from the student’s native language were permitted. ‘Heifetz always wanted his students to think musically rather than falling into the trap of thinking about music, and I think this imposed linguistic discipline was part of that goal.’

It’s important for us to understand that Heifetz worked as hard as he did so that he could be completely spontaneous and playful during a performance. ‘He didn’t have set bowings or fingerings,’ explains Agus. ‘Instead, he changed these according to how he was feeling in the moment, and he wanted the students to have this attitude of spontaneity, too. In the class, he would often ask a student to go back a few bars and to play again using a different set of fingerings. Occasionally, just after a student had tuned and was about to play their designated piece for the day, he would suddenly ask another student to lend their violin to the person about to play. He then instructed the first student to proceed on this completely unknown violin.’ All this was designed to promote a balanced, flexible mind and technique, so that the player was well trained to be ‘ready for the emergencies’, as he once said.

Read: How can violinists create a personal sound?

Read: Heifetz Cadenzas: Beethoven Violin Concerto

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

This article is an extract from The Strad’s December 2021 issue

-

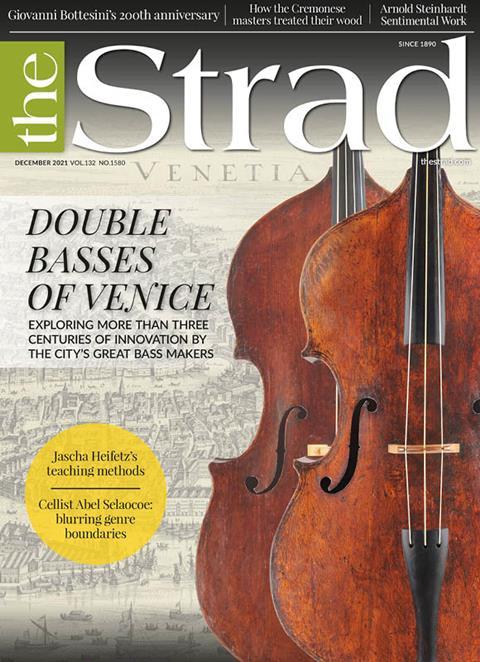

This article was published in the December 2021 ‘Double Basses of Venice’ issue

The north Italian city-state produced some of the country’s finest instruments . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- The Venetian double bass

- Celebrating Bottesini’s 200th anniversary

- South African cellist, composer and vocalist Abel Selaocoe

- Wood treatment on Cremonese instruments

- Heifetz as a teacher

Read more playing content here

-

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

This year’s calendar celebrates the top instruments played by members of the Australian Chamber Orchestra, Melbourne Symphony, Australian String Quartet and some of the country’s greatest soloists.

No comments yet