Alexander Technique specialist Alun Thomas uses a case study to illustrate how performance success stems from a grounding awareness of one’s feet

The following extract is from The Strad’s January 2022 issue feature ‘Alexander Technique: Thoughts That Count’. To read it in full, click here to subscribe and login. The January 2022 digital magazine and print edition are on sale now

Pathway one: gravity, our constant accompanist

Case study 1 – Simon

Simon often struggles to present his playing in what he considers the best light under the objectifying gaze of an audience, as he perceives it. Although he is a capable player, the stimulus of auditions, exams and performances tends to reveal serious insecurities in his playing. Helping him become aware of his ‘end-gaining’ – his overwhelming anxiety to ‘get it right’ – and noticing how this relates to a loss of an easy balance and energetic relationship with the ground has proved invaluable in addressing and solving these and other violinistic issues.

Simon takes Mozart’s Violin Concerto no.5 in A major K219 and plays the Allegro aperto of the solo exposition (example 1). Differences of opinion about musical gesture and characterisation aside, Simon’s playing is full of minor textual errors, rhythmic instability, muddy intonation and insecure shifts. It is, despite his obvious ability, musically incoherent. In playing for me, he might appear to have registered a challenge to his sense of self – the experience, perhaps, of being tested, rather than of ‘giving’. I sense an overarching, causative thread of ‘over-doing’ which is spoiling his playing, and decide that an exploration of his basic balance will be key in uncovering and eventually solving his problems.

‘Great playing starts at the feet’

That is violinist Pinchas Zukerman’s opinion, and (agreeing completely with his observation) I often suggest, rather drily, that violinists sometimes seem not to have legs. The hefty wear on the outside of Simon’s shoes is a clear indication of the precarious foundational platform he reveals in his playing and more generally. The inseparability of physical, mental and emotional balance is laid bare: Simon’s performance behaviour resembles someone skating on thin ice.

In common with many players, Simon has a tendency to lose the balance under his feet – an easy three-point contact (involving the so-called foot tripod, right) – at just the point where it is needed for maximum stability.

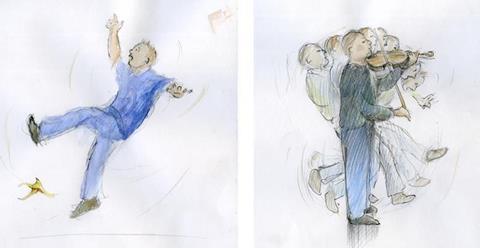

This lack of easy balance stimulates to varying degrees a subtle form of what physiologists and Alexander teachers call the ‘startle pattern’: neck clenched, head pressed back and down, legs and arms extended and stiffened, breath held. The ribs fix in response, restricting free movement in breathing and the visual field, as overall awareness is narrowed. Like slipping slowly on a banana skin, it is a modified panic reaction and is, surprisingly, more common than we might imagine in the practice room and on the stage (illustration 2).

Another process that sometimes mimics this effect is ‘concentration’. ‘To concentrate’ originally meant ‘to bring towards a central point’, but in order to realise our musical intentions, it’s so important that we maintain an expanded field of awareness and do not misdirect our efforts. As well as our breathing being affected, other common signs of this misdirection are an unnecessarily furrowed brow, lip-pursing and a head that is ‘poked’ forward towards the object of our attention. Generally speaking, overtightness in one area is compensated by undue slackness in another. Working to prevent all this well before it starts to appear can lead to a renewed sense of joy in playing – a refinement in skill that allows for more musical insight.

Illustrations: Adelaide Izat

ILLUSTRATION 2 (left) Playing with tension in ‘startle pattern’ is a modified panic reaction, like slowly slipping on a banana skin. ILLUSTRATION 3 (right) Exploring balance reactions to slight changes in foot contact points

I invite Simon into an exploration of ‘balance under the feet’, emphasising that this is not in any way an attempt to feel or find ‘the correct balance’ – to promise any such thing would be to invite more misconception. ‘Trying to feel’ is a most insidious contradiction, but just coming to an awareness of where we are contains within it the means to lessen habits’ hold on us.

Exploring the slight changes in foot contact and the muscular ‘tensing’ (balance reactions) that is engaged to stop us falling over, Simon describes ‘holding on to the front’ of the thighs when leaning slightly back from his ankles, and arms that ‘stop moving’ when at the ‘point of no return’ just before falling. Leaning forward will elicit in most of us similar bracings, as well as more universally specific tightening in and behind the toes (illustration 3).

Listen: The Strad Podcast Episode #26: Alun Thomas on Alexander Technique

-

This article was published in the January 2022 Steven Isserlis issue

The UK cellist discusses his new Bach companion and recording an album of solo works by British composers. Explore all the articles in this issue . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- Steven Isserlis on Bach and British composers

- 1773 ‘Cozio’ Guadagnini viola

- Alexander technique: it’s all in the mind

- LGT Young Soloists record Philip Glass

- Copying Stradivari’s 1715 ‘Titian’ violin

- Opportunities for young musicians post-Covid

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet