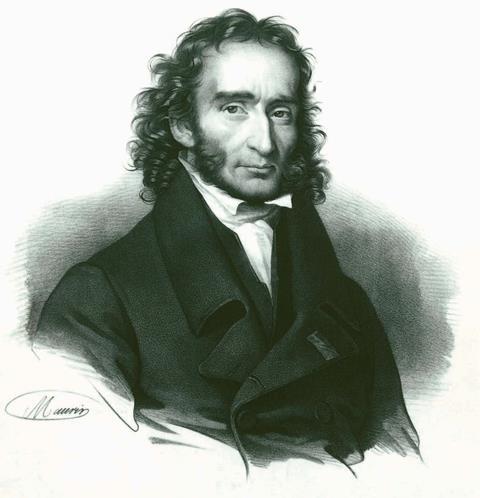

In a special feature marking The Strad’s 120th anniversary in May 2010, Julian Haylock examined perhaps the greatest violinist of them all

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Dressed in funereal garb, Paganini would float on to the stage like some ghastly apparition before launching into a blistering tirade of virtuoso pyrotechnics. Little wonder that many felt he was in league with the Devil. One thing is certain: the violin world would never quite be the same again.

PEDAGOGICAL BACKGROUND

Such was Paganini’s astonishing rate of progress that his various teachers struggled to keep pace with him. He began lessons aged seven with his father Antonio, who insisted on a strict regime of several hours’ practice a day. He then went through several local teachers in quick succession, including Giovanni Cervetto, a gifted player in the local theatre orchestra, and Genoa’s most celebrated violinist, Giacomo Costa. However, even the latter had little of lasting value to offer – ‘His principles often seemed unnatural to me,’ Paganini recalled, ‘and I showed no inclination to adopt his method of bowing.’ Of far greater impact was a concert given by the visiting Polish virtuoso August Duranowski, a former pupil of Viotti renowned for his arsenal of sleight-of-hand special effects.

Having outgrown the best that Genoa had to offer, in 1795 the twelve-year-old wizard headed for Parma, with the intention of studying with Alessandro Rolla, one of the most innovative virtuosos of his age. Just one lesson was enough to convince Rolla that Paganini would be happier with his ex-teacher Ferdinando Paer, who after a few lessons referred Paganini on to his own original teacher, Gaspare Ghiretti. Contact with Rodolphe Kreutzer and close study of Locatelli’s L’arte del violino provided further inspiration, but ultimately Paganini went his own way with a playing style that was utterly unique.

Recommended recordings

Complete concertos, etc. Salvatore Accardo, London Philharmonic Orchestra/Charles Dutoit DG 463 7542 (6 DISCS)

Violin Concerto no.1 Ilya Gringolts, Lahti Symphony Orchestra/Osmo Vänskä BIS CD 999

Violin Concerto no.2 Alexander Markov, Saarbrücken Radio Symphony Orchestra/Marcello Viotti WARNER APEX 25646 99872 (2 DISCS)

Violin Concerto no.3 Henryk Szeryng, London Symphony Orchestra/Alexander Gibson PHILIPS DUO 462 8652 (2 DISCS)

24 Caprices, op.1 Itzhak Perlman EMI 567 2372

TECHNIQUE AND INTERPRETATIVE STYLE

‘I never knew that music contained such sounds! He spoke, he wept, he sang! Paganini is the incarnation of desire, scorn, madness and burning pain,’ reported the German poet Heinrich Rellstab following Paganini’s 1829 Berlin debut.

‘His playing hit me like a meteor,’ enthused Goethe (‘comet’ was the word Berlioz chose in one of his reviews), ‘yet I was quite unable to unfathom its mysteries.’ ‘His faultless execution is beyond imagination,’ wrote Mendelssohn. ‘His style utterly unique and original.’

Indeed, there has never been a player of such legendary distinction who has broken so many of the basic ‘rules’. Paganini’s upper bowing arm was for the most part kept tucked in towards the body, leaving all the essential bow work to the forearm, wrist and fingers. When he did raise the upper arm in order to help negotiate rapid sequences of up-bow staccato, the elbow was thrust dramatically high in the air. His delight in ‘thrown’ bow strokes was completely at odds with prevailing standards, as was his tendency to play strong beats with an up bow and vice versa.

His left hand was even more unconventional due to its exceptional flexibility and unusually extended third and fourth fingers, making possible a comfortable three-octave stretch in fi fth position. Under the circumstances, normal rules regarding position changing simply didn’t apply. Above all, Paganini turned musical rhetoric on its head. From now on the most torrential passages of semiquavers were thrown off with the ease of a magician, while ‘slow’ movements were expected to carry a weighty expressive load on their slender shoulders.

SOUND

In the absence of recordings we shall never know the exact characteristics of Paganini’s sound. Yet despite (or perhaps because of) his penchant for lifted and ricochet bow

strokes, his priorities were a singing cantabile and strongly projected depth of tone above superfi cial brilliance. He once commented that ‘Stradivari only used the wood of trees on which nightingales had sung’, and noted of his 1724 Stradivari, with particular approval, ‘This violin has a tone as big as a double bass – never will I part with it as long as I live.’

STRENGTHS

Paganini’s technical mastery was virtually unprecedented. He could reportedly play even the most intricate pieces perfectly at sight, and accomplished his miracles with such executant ease that even those granted a closer look could not fathom his secrets. He had the rare ability to make even the slightest of virtuoso pieces sound inspired and significant.

He had the rare ability to make even the slightest of virtuoso pieces sound inspired

WEAKNESSES

Paganini’s facility was both a blessing and a curse, for when playing music whose intellectual and musical interest outweighed its purely technical challenges, he could appear less certain, restless even. His tendency to exaggerate both fast and slow tempos had a disruptive effect on music of Classical balance and sensibility.

INSTRUMENTS

Paganini owned a magnifi cent collection of 24 instruments, which included 9 Stradivaris, 2 Amatis (a small c.1600 Antonio and Girolamo, and a 1657 Nicolò) and 3 Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ violins. Although his general preference was for Stradivari, his favourite instrument was a 1743 Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ known as the ‘Cannon’, which he most likely received as a gift while he was in Livorno in 1802. Paganini later bequeathed it to the city of Genoa, where it still sits on display in a glass display case in the Palazzo Doria Tursi. A glorious 1740 Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ was played by Fritz Kreisler until 1931. Paganini’s beloved 1724 Stradivari was acquired by Sarasate in 1866 and is currently owned by the Musée de la Musique in Paris. Another outstanding 1724 Stradivari was last owned by the great Hungarian–French virtuoso Sándor Végh.

REPERTOIRE

It is easy to criticise Paganini for what appears to be his studious avoidance of the ‘classics’. Yet when he first emerged on the scene in the 1790s and early 1800s, the musical world was a very different place. The vast majority of what we now consider the central violin repertoire had yet to be composed, and the notion of audiences hungry for the music of the past was still some way in the future, inspired initially by Mendelssohn’s epoch-making performance of Bach’s St Matthew Passion in 1829. In an atmosphere when novelty was all the rage and the seeds of Romanticism had already been sown in the literary and pictorial arts, Paganini was at the cutting edge of virtuoso performing and composing, a beacon of inspiration for a whole generation of musicians. His playing career focused on his own compositions simply because there was little else around at the time that could match it for combined fl air and technical invention.

CHRONOLOGY

1782 Born in Genoa, Italy

1789 Begins violin lessons with his father

1796 Studies with Paer

1801 Settles in Lucca

1810 Begins touring in earnest

1813 La Scala debut makes him a national hero 1820 Ricordi publishes his fi rst fi ve opuses

1828 Viennese debut causes a sensation

1834 After stays in London and Paris, returns to Italy

1840 Dies in Nice, France, aged 57

The Strad is offering customers the chance to purchase print magazines from its archives, while stocks last. Get your copy here before they’re all gone!

Read: Unique wax cylinder recordings by Paganini’s only pupil identified

Read: Paganini’s ‘Il Cannone’ violin receives X-ray treatment

Read more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

American collector David L. Fulton amassed one of the 20th century’s finest collections of stringed instruments. This year’s calendar pays tribute to some of these priceless treasures, including Yehudi Menuhin’s celebrated ‘Lord Wilton’ Guarneri, the Carlo Bergonzi once played by Fritz Kreisler, and four instruments by Antonio Stradivari.

No comments yet