Although superhuman flexibility may initially seem like a gift, it also presents itself with challenges and injury. Adam Hockman interviews violinist Francesca dePasquale on how string players can approach hypermobility in their playing and treatment

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Hypermobility might sound like a gift—an extended range of motion that enables a person to move like an Olympic gymnast or gifted yogi. But for hypermobile musicians, there are unexpected challenges associated with superhuman flexibility, including pain and injury.

Violinist Francesca dePasquale, on the faculty of Oberlin Conservatory of Music, is all too familiar with being flexible to a fault. From a young age, Francesca’s extra range of motion and flexibility seemed normal to her rather than a medical condition. She could reach downward and back to put her palms flat against her upper back, flex her fingers backward past ninety degrees, place her hands flat on the floor without bending her knees, and extend her elbows ten degrees beyond a straight line. Eventually, though, her flexibility exacted its price. In her late teens, Francesca began to experience pain when playing her beloved instrument. ’It took me years to understand why this was happening despite performing instrumental techniques correctly. I wasn’t aware of the effort my body was making to support that technique. Through injuries and rehabilitation in my twenties, I learned how to support playing without pain.’

In her thirties, Francesca was diagnosed with hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (hEDS). EDS and hypermobility affect the body’s connective tissue, making it easy to dislocate a joint or bruise the skin, along with myriad other challenges. As Francesca learned about hEDS and how to keep her body in peak condition for traveling and performance, she passed her knowledge along to her students who showed similar signs of hypermobility.

What Is Hypermobility?

Hypermobility can manifest in various ways, with or without instability or symptoms. Someone who is double-jointed in one or more of their fingers has a fairly common form of asymptomatic localised hypermobility. Same for the ability to bend back the thumb to touch the wrist. Such examples of a greater-than-average range of movement can appear in fingers, hands, wrists, elbows, knees, shoulder blades, and any location on the body with joints and connective tissue.

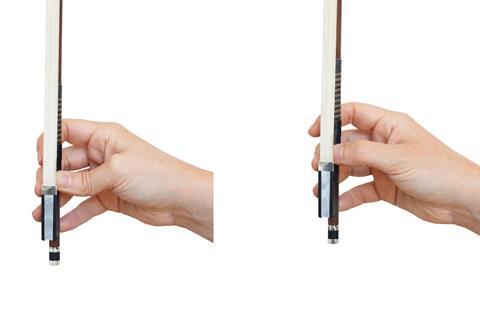

Francesca has observed that string players may manifest hypermobility in several ways while playing their instrument. On the right side of the body, you might see a player collapsing finger joints of the bow hold, commonly in the thumb or pinkie, while the rest of the hand and right side counterbalances to support the bow hold. Bowing incorporates the swing of the arm, the movement of the right shoulder blade sliding back and forth. If the shoulder blade is winged out, it’s limited in how much it can move, and that makes it difficult for the arm to do what it’s supposed to do.

Francesca says that scapular winging can decrease the space in the shoulder ball socket. ’If the shoulder blades are winging out, the tendons, nerves, and ligaments that run through that area have decreased space, which can lead to injury through the repetitive motions during practice and playing.’

As for the left side, a hypermobile player might press and collapse any of the fingers that affect pitch and vibrato. The pinkie is the usual culprit since it is the weakest finger.

Awareness Is Key

Awareness of whether a musician is hypermobile is essential to preventing career-threatening injuries or exhaustion that limits daily activities. Medical providers diagnose hEDS and hypermobility, but anyone can visit the Ehlers-Danlos Society website to complete its Diagnostic Criteria for Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (hEDS) checklist and understand the symptoms. The Society offers a registry of vetted providers—doctors and physical therapists—who have experience with hypermobility.

Managing Hypermobility

Hypermobility isn’t curable, but hypermobile musicians can manage their condition by developing awareness and limits that stave off exhaustion and injury. Francesca and other musicians like her have learned to maintain a productive performance and teaching career through careful planning and attention to their bodies. Here are a few strategies.

Strategy 1. Mindful Movement

It takes longer for hypermobile people to gain muscle. There’s a phenomenon called delayed onset muscle soreness whereby it can take 24 to 48 hours to appear after working out. You may not realise you’ve overdone it for two or three days. But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t train for strength. Mindful movement is the most important thing a person can do to improve their quality of life. It builds knowledge of the body and strengthens the muscles so they can support joints where connective tissue does not.

Francesca says, ’Exercises should start slowly and steadily. If someone has winging shoulder blades, there are exercises to strengthen the rhomboid muscles that support them. Start with body weight and then slowly move to resistance bands. Five to ten repetitions can be a good start.’

Strategy 2. Movement Cravings

The weak connective tissue of hypermobile joints leads to soreness and tightness in the muscles that movement alleviates. Francesca recommends activities like mindful walking, swimming, or Pilates. Yoga is also beneficial. Make sure you find an instructor who understands hypermobility and accommodates your unique challenges. ’Most importantly, find and work with a physical therapist who is knowledgeable about hypermobility,’ Francesca notes. In short, give the body the movement it craves, and the strength training it needs.

Strategy 3. Pain management

Exercise can lead to fatigue and soreness, but even simple daily activities can be exhausting for hypermobile individuals. Overextending your joints at work or during routine activities may leave you feeling depleted. Francesca recommends several methods for managing fatigue and pain: trigger point acupressure, self-massage with a lacrosse ball, red light therapy, and Epsom salt baths. Rest and pain management are necessities for hypermobile people.

Strategy 4. Protein intake and supplementation

To increase muscle mass, hypermobile people must consume sufficient calories and protein to support their muscle growth and overall musculoskeletal health. ’Discuss supplementation with your doctor, like using creatine. Adding electrolytes to water is also a game changer for people with disorders associated with autonomic nervous system regulation (dysautonomia), a common comorbidity for those with hypermobility. The added salt, potassium, and magnesium increase blood volume, which helps the body retain hydration that dials down symptoms of dizziness and lightheadedness.’

Strategy 5. Rest and recovery

Muscles need rest from practice, daily activities, physical exercise, and the effort needed to stabilise loose joints. Getting plenty of sleep is essential for maximising mindful movement every day. Supportive pillows that cushion the curve of the neck or other body parts can relieve pressure and prevent additional fatigue to hypermobile joints.

Hypermobile Musician

In classical music, there can be a stigma attached to injury. Disclosing a previous or current injury may be seen as a sign of weakness. In reality, many musicians experience injury or fatigue, whether hypermobile or not. Francesca hopes knowledge about hypermobility creates transparency around injury, prevention, and rehabilitation. She has created Hypermobile Musician, a site with resources for musicians and teachers who want to understand the challenge and benefits of hypermobility. All of Francesca’s hard-earned knowledge and experience as a hypermobile person and teacher can be found in this one spot designed to educate musicians.

Taking Action

If you have a student who fatigues easily from playing or appears to be more flexible than other students, consider initiating a conversation with them about hypermobility. You might encourage them to seek advice from a healthcare provider. If someone suspects they might have symptomatic hypermobility, they should get screened to see if they might have hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (hEDS) or hypermobile spectrum disorder (HSD). These are clinically diagnosed through a series of tests. Currently, there is no genetic marker for the hypermobile type EDS.

A Challenge, Not a Barrier

’With the right awareness and tools, much of the pain and injury associated with hypermobility can be mitigated,’ says Francesca. Teachers, educate yourselves and share this knowledge with your students. If they aren’t affected by hEDS or hypermobility, this awareness might help one of their current or future colleagues.

ABOUT FRANCESCA DEPASQUALE

Francesca dePasquale is a violinist on the Oberlin Conservatory of Music and Juilliard Pre-College faculties. She is an active soloist and chamber musician appearing with Chameleon Arts Ensemble of Boston, Manhattan Chamber Players, and Aletheia Piano Trio, which has performed across the United States, China, and Korea. Francesca is creator of Hypermobile Musician, an online resource for hypermobile musicians and the educators who teach them. She is former teaching assistant to Itzhak Perlman and Catherine Cho at The Juilliard School.

ABOUT ADAM HOCKMAN

Adam Hockman is a practice and performance consultant on the faculty of the Heifetz International Music Institute. He applies his training in behavioral and learning science to music practice, performance, and teaching, and writes about these subjects for different music sites and magazines. Learn more at adamhockman.com.

Read: Little lessons for teachers by teachers: violinist Chloé Kiffer

Read: Learning about your performance anxiety: Adam Hockman

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

5 Readers' comments