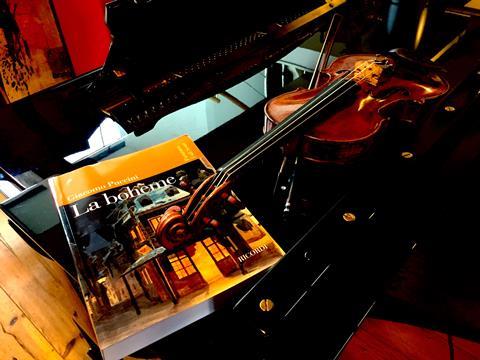

How can the rich orchestration and lyricism of Puccini’s La Bohème translate to only two instruments? Violinist Mathieu van Bellen shares how

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The idea to transcribe an entire opera for violin and piano was created over several years. Pianist Mathias Halvorsen and I have known each other for quite some time, and have played a lot of chamber music together in various festivals. Mathias is always trying to explore the unusual; whether it’s works by lesser known composers, or unusual formations.

Another fascination for both of us was always opera. What intrigued us particularly was why this genre is so popular, something neither us deeply understood. An opera usually has a huge number of people involved, from singers to orchestral musicians, conductor, people in charge of staging, choreography, all of which have a huge effect on the music itself. We wanted to get to the core of the music and highlight that particular element of the opera without it being affected by the staging and acting.

The next part was to search for a suitable opera, one without too many characters in it, not too long, lyrical melodies, not too much chorus, and a lot of variation. Our sights were quickly set on Puccini. From then on it was picking between La Bohème, Tosca or Turandot.

We chose La Bohème.

Of course we were inspired by the transcriptions of famous melodies that were made by people like Kreisler and Godowsky. But we wanted to transcribe the entire opera, from the first to the last note. First we decided to divide up the roles. We definitely didn’t want ‘violin plays melody vs piano plays orchestra’. In the end the violin did end up taking the characters of Mimi and Rodolfo, which posed issues with the conversations that they often have with each other. Many of the other parts were taken by the piano, like Marcello, Schaunard and Colline. I find the part of Colline works astoundingly well in the piano, I wasn’t sure how his aria would work near the end of the opera, but somehow Mathias always gets the atmosphere completely right.

One important rule was that we would try to fill in orchestra parts as much as possible at all times where it would suit. This means that you can be playing a melody, but all of a sudden jump to an orchestral part to play two chords and jump back to the melody. As a base we used one of the piano transcriptions already made, but we have added many extra orchestral lines, and I as a violinist ended up playing a lot of the different parts at all times.

The transcription took a long time to make, experimenting with which techniques we could use. We opted not to use any ‘unusual’ techniques like knocking on an instrument or preparing the piano in any way, but to stay rather conventional. Picking which octave to play in, or whether to use octaves in general is actually still an ongoing search, as we try to be as lyrical as possible without overdoing it.

In the end we haven’t exactly written out the arrangement yet as conventional notation, both Mathias and I have slightly different parts, otherwise there would simply be an absolute overload of information on each page for both of us to understand during a performance.

One of the big advantages we learnt to appreciate was the flexibility (or in fact the contrary) one can get with two people, which is much more difficult to achieve with a full opera orchestra, singers, staging and acting. As a result of this we were getting a lot of inspiration from Puccini’s markings. We feel because we were able to only worry about the music without the burden of ‘extra-musical’ timings due to staging issues or conventional singing traditions, we were able to stick very closely to the score, staying as close as possible to Puccini’s tempo markings and rubato’s, which he indicated incredibly clearly.

Of course we are not 100 per cent mathematical in our execution of Puccini’s markings – this is not the purpose of this music in our experience – but this way we learnt so much about the full structure of the opera, something which we feel is not always able to flourish in a fully staged production. Having said that, the conductor who premiered La Bohème, Arturo Toscanini, recorded it on its 50th anniversary, and his recording is by far the closest to the score that Puccini wrote.

Our album is a ‘live’ recording. We spent three days recording for the microphone, but then we played a full performance for a live audience, and actually ended up using most of that concert as the base, with very few corrections. Playing the opera in full with the knowledge that you already have all the material freed us, and the days of the recording session put us in a state of love towards this music. As a violin/piano duo, one is not used to playing a piece in four movements which lasts more than 1.5 hours, so in a recording session you can easily get bogged down on details and forget about the overall structure. We dared to approach the recording in this way also because of the unusual arrangement, and we believe that the spontaneity of the live performance will enhance the experience of this opera in our version.

Mathieu van Bellen and Mathias Halvorsen’s recording of La Bohème for violin and piano will be released on 18 November 2022 on Backlash Music. Find out more here: https://backlash.lnk.to/boheme

No comments yet