In conversation with The Strad, New York-based jazz bassist, improviser and composer Michael Bates outlines how he arranged seven Lutosławski works for jazz quintet and string quartet

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub.

How do you blend improvisation into a notated composition? How do you integrate jazz influences into an arrangement of a contemporary classical piece? How do you successfully compose for jazz quintet and classical string quartet together? These were all things that New York-based jazz bassist, improviser and composer Michael Bates had to consider in a recent project. In his album Metamorphoses: Variations on Lutosławski, Bates’s jazz quintet Acrobat (comprising clarinet, bassoon, violin, bass and drums) joins forces with the fittingly named, Lutosławski Quartet. The album features Bates’s arrangements of seven works by Polish composer Witold Lutosławski, spanning the composer’s career. The new works feature improvised sections, interspersed throughout notated material, and takes full advantage of the inter-genre ensemble at hand, with jazz influences running throughout the album. The Strad spoke to Bates about the arranging process, what makes Lutosławski’s music so appropriate for such a project, and the unique opportunity to have jazz and classical musicians improvising together.

How did the project come about?

A couple of years ago my quintet, Acrobat, played at the Jazztopad festival in Poland, and saw the Lutosławski Quartet perform. I was knocked out by how they played and thought about how we could collaborate and from what angle. Seeing as they’re a Polish string quartet and I’m a fan of Lutosławski, this idea came to me. On the flight home I was already writing notes and sketches. Fast forward six months or so, and we flew to Poland to record the full album over three days.

What is it about Lutosławski’s music that lends itself well to this project?

Among jazz musicians, he’s been an iconic figure given that at one point he started using improvising and indeterminate music to compose. His string quartets are like that. What’s so interesting is that in the late 50s, his music also included a lot of folk elements, but then it completely changed when he heard John Cage’s music. So there’s a broad spectrum of music to choose from.

His music is elegant but also fierce. He’s not afraid of ugly beauty. And all the while, so detailed. You can draw from the tiniest bit of material and make a whole concert out of it. So, when choosing which music to use for this project, I was hearing what it was giving me as an improviser and picking the stuff that lent itself to extrapolation.

What did the compositional process for this project look like?

Especially with music like this, which isn’t always tonally based, and contains some gestural material, I’m looking for aspects of the music that will launch the musicians off into a creative space. When you have string players who can improvise well and jazz musicians that can play chamber music, the arrangements should play to those strengths.

As for instrumentation, most of the writing was not necessarily thinking about the quartet as separate entity, although they do function as that sometimes. I was thinking in pairs a lot: bassoon with cello, bassoon with bass, bass with drums, clarinet and viola, and so on. And other times, the rhythm section was against the whole thing. When you start thinking like that, the math gets kind of awesome. The orchestration opportunities are super exciting.

So extrapolating gestures you feel are most prominent and expanding them?

Yes. And once I’d done my score study, made my road map, and had written most of the material down, it’s open season. I’ll always do something respectful, never something that’s cutesy or with a wink or counter his intention. But at the same time, I’m already ‘ruining’ it so no need to be too precious either.

What do you define as being respectful towards a piece when arranging it?

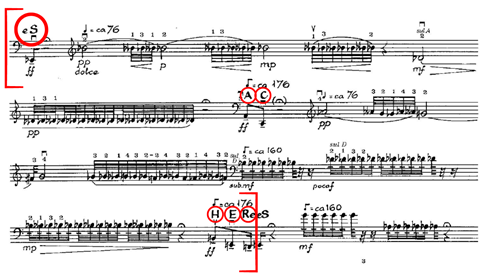

Listening to the intent. Some things just lend themselves perfectly to that, so you don’t want to touch them. But if you take something like Sacher Variation, originally for solo cello and now for string quartet, bass and drums, it’s largely gestural, and I dismantled it almost entirely. I took the row it’s based on, which is Paul Sacher’s name [S=E flat, A=A, C=C, H=B, E=E, R=D for re], for whom the original work was written for. So you hear the row in its entirety at the beginning, then several gestural things and then it’s literally pulled it apart.

How did you go about writing improvised parts for classical musicians?

I didn’t want to write music that involved taking people out of their comfort zones. I think that classical musicians have the most incredible language at their disposal. They’ve absorbed this music so profoundly, so to say to them, I want you to improvise in jazz context is doing a disservice to everyone. It was creating a context in which they could let go.

A large component of how I wrote these is by arranging the composed material that would then launch into improvisation. I’ve found that to help create improvising context, I have them work towards the next section of written material. I’ll also often bring in the rest of the group in the background, creating more context and allowing them to focus on what they’re doing and to create a forward motion.

What do you think strings add to a project like this? Especially in your arrangement of the Wind Trio [originally for clarinet, oboe and bassoon], which doesn’t have strings in the original composition?

I think we’re both going to agree, that some of the best music ever written is string quartet music. I mean, right?!? They can do anything. Especially the Lutosławski String Quartet. They can create textures like no other ensemble and the possibilities are incredible. For me, as someone who loves classical music and is a trained jazz musician, the most incredible thing to do is play with strings – a rare thing for us.

Regarding the Wind Trio, I spent time listening to the original piece and found a 30-second chunk that my entire arrangement is based on. This was one of the pieces I wanted to channel a free jazz element while maintaining a structure. With the strings at the beginning, it’s about reinforcing those crazy lines on top of a group texture and then allowing them the space to improvise on top of a bad-ass groove with the drums. So in this case, it’s about textures when it comes to strings.

What is special about having jazz and classical musicians improvising together, rather than just jazz musicians?

They influence each other wonderfully. The jazz musicians potentially bring out an aspect of the classical musicians that they might not easily access to when not around improvisers. Maybe it’s a rawer way of approaching a piece that makes everything fit together or something that they hear and realize, ‘Oh! That’s the sound’. Maybe they hear the clarinetist or bassoonist using that language in a creative way and that lifts them.

And conversely, the incredible attention to detail and beautiful line that classical musicians often create will inspire everybody on the improvised side of things to play a more dynamically or blend in a different way. It raises the bar all around. It’s not about trying to get anyone to draw a different language out of themselves, but to heighten what they already have.

Listen: The Strad Podcast Episode #14: Nicolas Altstaedt on the Lutosławski Cello Concerto

Read: ‘Your own voice must be in charge’: Creating an improvised violin concerto

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub.

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

American collector David L. Fulton amassed one of the 20th century’s finest collections of stringed instruments. This year’s calendar pays tribute to some of these priceless treasures, including Yehudi Menuhin’s celebrated ‘Lord Wilton’ Guarneri, the Carlo Bergonzi once played by Fritz Kreisler, and four instruments by Antonio Stradivari.

No comments yet