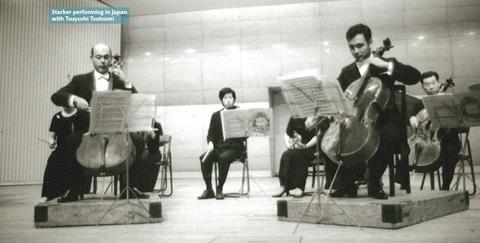

2024 marks the centenary of the legendary cellist János Starker. Tsuyoshi Tsutsumi shares his memories of the cellist in this tribute from the April 2014 issue of The Strad

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The first time I met Professor Starker was in December 1960. He came to Japan and I went to his concerts. I thought he was so perfect as a cellist, particularly his Kodály Sonata. I didn’t know the piece and he managed it so impressively, both technically and expressively. I had discovered a new world. I was 18 and had received a Fulbright scholarship to study in the US. I was looking for a teacher so I played the Dvořák Concerto for him and he invited me to Indiana.

He always said that one should strive to be a true professional, so he was strict with himself as well as with his students. He demanded that one be able to control one’s instrument in order fully to express oneself musically. He emphasised the release of extra tension and also the idea of the preparation and anticipation. In one of my first lessons with him I was shocked when he said, ‘Tsuyoshi, when you start the first note of a piece you should already know the last note.’ One should know the whole picture beforehand, not just go along. Until I went to study with him I believed one should spend many hours practising the instrument.

He said I shouldn’t over-practise, but really concentrate. In difficult passages, instead of repeating something that doesn’t work, just stop and think. What doesn’t work? Maybe my motion is too fast, or some preparatory motion is missing or incorrect, or different muscles should be used. By knowing exactly what you do, you can eventually teach yourself.

Whenever he had to speak, his thoughts were clear, precise and honest

Rather than practising for six hours, he suggested three or four and spending the rest studying other things to broaden my musical and human horizons, which would come into my playing. If I was studying an Impressionist piece he would bring out a book on it and talk about painters.

When I went to Bloomington in 1961 I didn’t speak English well. He expected that I should put everything I do technically or musically into words – not only spoken but also written. Early on, if lessons were an hour I would spend 15 minutes playing and the rest talking about music and technique. It was very hard for me but it helped, and now it helps my teaching.

When I went to study with him I could play the cello at a certain level, but I had to restart, by playing scales without vibrato. He emphasised that from one fi nger to the next there should always be release and this applies to any shift, up or down, and also to the right arm. Physical motion is based on circular motion and this usually applies to both arms. Everything is logical and continuous. He stressed the total coordination of movement. When one plays the cello the whole body should participate, including your feet. We don’t only play the instrument with our arms and hands. He sometimes asked students to tap their feet while playing, so they act like a conductor and you have to follow. I use this a lot when I teach.

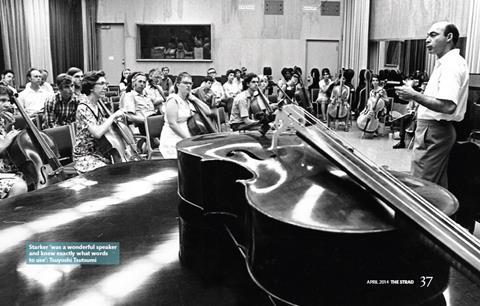

I became his assistant in the autumn of 1963. He always used the word ‘help’ rather than ‘teach’, and he never liked to use the word ‘masterclass’. He said, ‘I don’t want to be a master.’ He was a wonderful speaker and knew exactly what words to use in order to express what he wanted to say.

He didn’t keep talking and talking, but would say something specific and to the point. Sometimes he demonstrated by playing, which was always perfect. He had it all figured out. Whenever he had to speak or give a speech his thoughts were so clear, precise and honest. He insisted that one should be honest to oneself and to the music.

INTERVIEW ARIANE TODES

Read: How to play fast passages without tension, by cellist Tsuyoshi Tsutsumi

Watch: Suntory Hall president and cellist Tsuyoshi Tsutsumi performs at homes

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub.

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

American collector David L. Fulton amassed one of the 20th century’s finest collections of stringed instruments. This year’s calendar pays tribute to some of these priceless treasures, including Yehudi Menuhin’s celebrated ‘Lord Wilton’ Guarneri, the Carlo Bergonzi once played by Fritz Kreisler, and four instruments by Antonio Stradivari.

No comments yet