After encountering Suzuki’s teaching in the US, Helen Brunner was convinced it should be brought to the UK. That the task should fall to her seemed a matter of destiny, she tells Caroline Heslop, in this article from September 2000

Helen Brunner says that in the past she’s resisted doing interviews because the story of her life is so complicated. Its a curious story, in her own words, ’because it’s got magic in it - and miracles - and it’s very difficult to express in a way that doesn’t sound completely off the wall!’ Particular experiences among many she cites as magical or miraculous include nearly dying when she was 19 and having an out-of-body experience’ which has given her a fearlessness that has marked her life; looking for a violin teacher for her young children in upstate New York in the 1960s and finding one of the first trained Suzuki teachers, thereby becoming one of the first Suzuki mums; her children the first Suzuki children; reading Suzuki’s book Nurtured by Love and feeling such a powerful response that she couldn’t stop crying; realising in an almost dream-like state while on a flight to Vienna in the early 70s, that she had to bring Suzuki’s teaching to the UK, that it had to be her, that she was in some way ‘chosen’. Brunner did bring Suzuki’s ideas to the UK and in so doing revealed herself as a truly extraordinary violin teacher.

While Brunner declares herself a missionary for Suzuki and continually acknowledges her debt to him. her former pupils - who number several well-known young musicians including Katharine Gowers - are swift to acknowledge their debt to her.

Jenny Stokes, who at 21 is planning a career as a soloist and in chamber music, says quite simply: ’Without her, I’m not sure I’d have carried on. She is so inspirational and has this fantastic energy which she gives to her children. She gets to know the child, finds the musicality and draws it out. If it weren’t for Helen I’m not sure I would have got past the seven or eight-year-old tantrum phase.’

Colleagues, too are keen to praise her. US violin teacher Edward Kreitman says, ’Helen opens her heart to everyone with such enthusiasm you can’t help being taken with her.’ He flew to London in January to be at a 60th birthday concert in her honour given by her past and present pupils. ’What was most significant was not the high level of music-making - and it was excellent - but the joy that was present in the playing of all these young musicians. They were playing their hearts out for their teacher; he says.

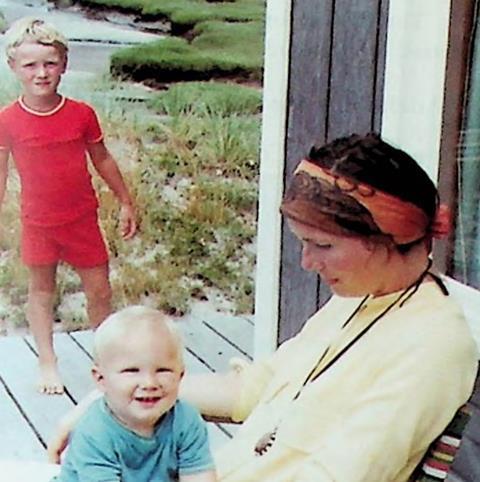

Brunner was born in 1940. the fifth of six children in a musical family. She went to study at London’s Royal College of Music and was looking forward to a career in music when she fell ill at the age of 19. Her career went on hold and then in her early 20s she had four children in swift succession. With her husband and young family she went to live in Westchester County, New York, and at the age of 25 felt she was ready to resume her musical studies, taking lessons with Oscar Shumsky in New York.

This coincided with the arrival of three Japanese violin teachers who had come to the city to introduce Suzuki’s new way of teaching the violin. Brunner enrolled her children as students. She was not prepared initially for the fact that she had to be present and participating at the lessons, nor that the children had to go twice a week for a group session as well as to their individual lessons. She remembers being baffled by the pink plastic record the children were meant to listen to in order to learn their music.

She thought it all rather strange but planned to pursue it while they were in the US, intending to find ’proper’ teachers when they returned to the UK. Of course it didn’t work out like that at all.

Possibly the most significant point of Suzuki’s approach, and the one that Brunner is most keen to underline, is the principle of the mother tongue. She describes how Suzuki left Japan as a young man and came to Germany. His father made kotos (Japanese musical instruments) but had diversified into violins in the early 1920s ahead of anyone else in Japan. The younger Suzuki lived in Berlin where he lodged with Albert Einstein, the physicist, and studied the violin with Karl Klinger for about six years.

While there he tried to learn to speak German and watched the native children around him learning the language. It forced him to arrive at this conclusion, says Brunner: ’If a child can speak the mother tongue after six years so perfectly and I, who really try, cannot, there must be something profoundly wrong about the way I m being taught and something profoundly right about the way’ children are taught.’ This revelation led him to change his life’s ambition towards finding the key to how people speak their own language. When he returned to Japan shortly before the Second World War he applied the principle to learning the violin. Developing this insight to recognise that a child has to start learning very young, that the parents’ role is crucial and - most important of all (Brunner emphasises this with great urgency) - a child learns to speak by listening first, he laid the foundation of what has become known as the Suzuki approach.

Brunner is convinced that Suzuki was right when he said you should access music through what is going on inside your head. The Western tradition, she believes, which teaches children to access music through written music, is wrong. It continues to amaze her that, when Suzuki teachers and pupils the world over have proved how successful the approach is, it hasn’t whistled through Europe, with every child learning their instrument - and indeed other subjects this way. She comments that leading musicians and teachers still give the impression that music is an inherited trait. To her it is obvious that it is not it has to be taught in the right way.

When Brunner returned to England at the end of the 60s she decided she must try to bring over some Suzuki teachers. She wrote 200 letters to musical and educational establishments nationwide suggesting that they invite someone from Japan and offering to support the project. She got nothing but silence or negative responses. It was perhaps this frustrating rejection that triggered her sudden intuition while flying to Vienna that she must become a Suzuki teacher herself. Back home, a letter awaited her from the Rural Schools Music Association in Hertfordshire saying that they were interested.

The early 70s saw Brunner living back in west London and tentatively beginning to teach the violin the way she had watched her children being taught in the US. She remembers posting letters through nearby letter-boxes inviting her neighbours and friends to bring their children for her to teach. It all very quickly took fire and at the same time the Hertfordshire experiment was launched. A steering committee was formed which included Gene Sadler, Sheila Nelson, Gertrude Collins, Lady Redcliffe Maude and Brunner herself.

With money from the Gulbenkian Foundation and the Leverhulme Trust they were able to invite two American Suzuki teachers, William Starr and John Kendall, to offer training to music teachers in the county’s schools and to monitor the experiment. It lasted for four years. Brunner acknowledges that it wasn’t a complete success because not enough teachers were prepared to commit themselves, but for her it was wonderful; for the first time she had Suzuki-trained teachers on hand, living in her house and teaching her more and more about the Suzuki approach. Soon after, in 1974. one of Suzuki’s own students came to live with her.

Brunner, still youthful and vibrant at 60, continues the same active schedule she has led all her life, which invariably includes teaching from seven in the morning. She plays with the Meridian Quartet and is planning to study for a fellowship diploma. In addition to her teaching in London, she travels all over the world training teachers for the British Suzuki Institute. Brunner gives her students enormously varied opportunities for performing. Jenny Stokes recalls how aged nine or ten, she and her group performed Autumn from the Four Seasons in Scotland, with Suzuki in the audience. Apparently he watched their vibrant and confident performance and said, ’Those must be Helen Brunner’s pupils.’

The training of teachers is crucial to the success of the Suzuki method. Although Suzuki’s approach is recorded in eight violin books of repertoire, there is nothing in the books that tells you how to teach them until you have trained as a teacher; you won’t know which place in the book to introduce vibrato, to teach how to lift the bow or to learn a new finger pattern. As Brunner says of the books, ’they are like ’hangers upon which we attach the technique.’

Brunner has a strong link to the British Suzuki Institute, which offers training and support to all Suzuki-trained teachers. It was Suzuki’s vision that all his teachers and pupils were part of his family. This vision continues. Brunner not only views her relationship with her pupils as like that of a family but finds a consensus among Suzuki teachers. In London, for example, they are agreed that they use the Suzuki music but that they supplement it. ‘We all chop and change a bit and leave things out in the later books and supplement with material of our own choosing,’ she says.

In tune with the Suzuki ethos. Brunner is also sensitive to the cultural realities of being a young musician in Western Europe. She knows that being a good sight-reader is vital to achieving success in national youth ensembles. She estimates that all her pupils are the equivalent of grade eight by the time they are twelve and many join the UK’s National Youth Orchestra and play with Pro Corda - a national chamber music academy. Her pupils often start aged two or three. She teaches them to read music from an early stage but still retains the principle of letting them listen first and access the music from what they hear in their heads.

It all sounds pretty demanding for pupil, teacher and, perhaps most of all, parent. But Brunner has very few drop-outs. She comments, ’I avoid praise and blame. Overt praise can get in the way. I work on the basis of acknowledgement and affirmation: “Yes. Good. Fine.” I can also praise the sound - “I love that C sharp.” “Well done Mr two (second finger).”’ Brunner talks of the strength that group members who work together from the time they are three years old find in each other. Her pupils have to do an hours practice a day, something they have to find their own motivation for. She thinks that quite often they overcome any resistance because of the group lesson and their commitment to each other.

Brunner didn’t meet Suzuki until 1979. She recalls that she saw him lecture in the US in 1976 and that she was steeling herself to leave the lecture early to collect her nine-year-old daughter who was waiting.

Suddenly Suzuki put down his microphone and made his way to the back of the stadium with an interpreter to where she sat. The interpreter said to her, ’Suzuki Sensei says you can go now.’ She was amazed. He had apparently read her mind. Then in 1979, when she was introduced to him personally, he said something to his wife in Japanese who translated it as, ’Suzuki Sensei wants to know what took you so long?’ She feels she has always had a very close affinity with him. As she puts it, ’it’s something to do with God and Happenings and with my extraordinary life.’

Brunner graduated aged 43 from Matsumoto Suzuki Institute as a Suzuki violin teacher. Although her background is western, it seems she is moving in a more eastern, philosophical Buddhist direction. She goes to yoga classes and has a spiritual guide in Fiji called Adi Da. Tall, blonde, beautiful and visibly inspirational, Brunner shares her extraordinary zest for life with her own family, which now includes seven grandchildren, and with her extended family of pupils and their families.

Topics

Suzuki teaching: Every child can

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

Currently reading

Currently readingSuzuki’s ambassador: Helen Brunner

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

No comments yet