Associate concertmaster of the Sofia Philharmonic Orchestra and session orchestra violinist Alexandra Gorski explains the high level of sightreading required from session musicians, as well as principles she employs to nail those one-take wonders

Sightreading is one of those essential skills that, despite its necessity, is often avoided by experienced and studying musicians alike. Understandable- it’s immensely complex and arduous, all while having the unfortunate reputation as mainly an examination or audition requirement.

In reality, sightreading is vital to great musicianship, and has countless practicalities in the professional world.

In my experience, the requirements of a professional musician are vast and varied. There are instances when preparation and practice are absolutely crucial, like when playing with a performing orchestra. Playing as associate concertmaster of the Sofia Philharmonic, it is important to arrive to rehearsals with existing knowledge of the material, having studied the text and practiced prior. It’s definitely not the place for sightreading!

However (and contrary to popular belief), there are arenas in the performing world that rely and operate exclusively on sightreading. Recording and session work are fantastic examples of environments that demand its musicians to have a remarkably high level of sightreading ability. As a member of a few recording orchestras, I’ve seen firsthand that without a practiced method and experience as a sight-reader, it could be almost impossible to perform.

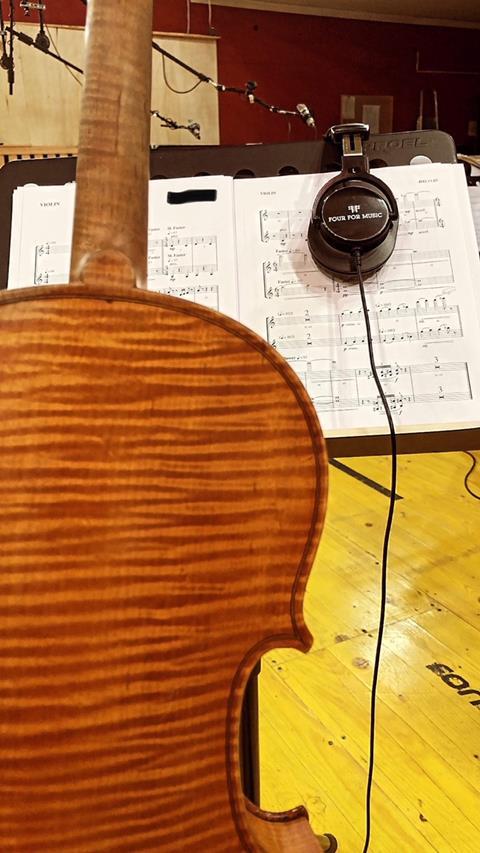

In contrast to the Philharmonic, playing as a member of the Sofia Session Orchestra has little to do with knowledge of the material or prior practice. The Sofia Session Orchestra & Choir are the musicians at Four For Music (FFM), an audio recording company responsible for the music of many incredible movies, TV shows, and video games. Some of the most recent and notable contributions of FFM include recording the music for Solo: A Star Wars Story, Netflix’s The Crown and The Witcher, Age of Empires IV, The Lighthouse, Catherine the Great, Assassins Creed, the Oscar-nominated Hair Love— and every single one of these projects were recorded by musicians who were sightreading.

Read: My audition journey: Alexandra Gorski, Sofia Philharmonic Orchestra

Read: ‘It is even unnecessary to know the names of the notes’ - From the Archive: February 1942

There is no preparation for a Four For Music session; we don’t know what we will be recording until arrival, and due to the high-profile nature of our projects, it is sometimes impossible to receive the music until just minutes before the start of the session. Recording starts from the very first take, with limited time to produce a finished product, which in this case, could be the soundtrack to an entire season of a TV series or video-game- literally hours of music.

There is little to no room for error when playing in a recording orchestra: a small mistake in intonation or an escaped cough from one musician is enough to scrap a previously great take, and force the entire orchestra to start again. Recording work dictates that its musicians be able to sightread at an extremely high level and learn the material quickly, all while producing a beautiful and nuanced sound in a high-pressure environment with restricted time.

Although these demands may sound unending and complicated, there are methods to improve your sight-reading and make the job more manageable. When you arrive the standard 15 minutes before a session and are greeted with 78 pages of material on your stand, it can be daunting and unclear even where to begin! Scanning through the entirety of the music is the most efficient and productive technique a musician can use, and is, in my opinion, the most critical aspect to being able to both sight-read well and learn volumes of music quickly. Scanning is a method where a musician briskly reads through music while observing important performance directions, tempi, melodic or rhythmic patterns, simultaneously identifying any dangerous passages or difficulties.

This technique allows you to recognise and prioritise sections of music that require more attention than others - you may not need to look through those pages of tremolo or sustained fortissimo whole notes, but those four lines of solo staccato passages in C sharp minor/presto certainly deserve some attention! Scanning offers a basic outline to the entirety of the work, allowing you to prepare and concentrate on what is most relevant in the part, in that very limited time before the session begins.

At the start of each recording, and after scanning through the music as a whole, it is imperative to make note of what I and my students call ’The Big Three’: key signature, time signature, and tempo. Ignoring this principle and basic information invites mistakes that, with one glance, could have been easily avoided. Luckily in a recording orchestra, observing the time signature and tempo is made a bit easier than in other situations- our headphones offer us a click (essentially a metronome) two bars before the start and throughout the entire recording, while a nearby TV screen reports our beat and bar counts.

Observing tempo, subdividing, and managing tricky rhythmic patterns while sightreading is made infinitely easier with rather than without a click! Regardless of the situation, taking a few seconds before the start of sightreading to mentally prepare, determine important information, and choose an appropriate tempo will ensure a more successful execution.

Though these methods can (and should!) be employed in all aspects of performance, sightreading is ultimately a learned and practised skill. No musician is a natural-born sightreader, and proficiency in sightreading is only cultivated with years of attentive practice. It is significantly more than just an examination or audition requirement, or even an added skill to an existing repertoire; sightreading is an absolute necessity for a major portion of the professional performance world. With practice and dedication towards sightreading, musicians can expect open doors to countless amazing musical opportunities, and more importantly - a greater confidence in their own playing.

'It is even unnecessary to know the names of the notes' - From the Archive: February 1942

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

Currently reading

Currently reading’There is little to no room for error’: Sightreading in a recording session orchestra

- 5

- 6

- 7

1 Readers' comment