US correspondent Thomas May speaks with Jessica Meyer about the synergy that fuels the charismatic violist’s work as a composer and collaborator.

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

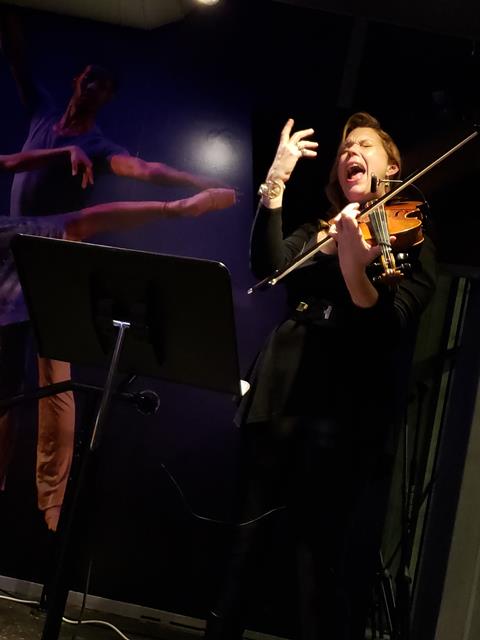

The award-winning composer and violist Jessica Meyer is an unclassifiable phenomenon even in today’s genre-defying contemporary music sphere. Meyer has been carving a unique space through her extraordinary blend of creativity, charisma, technical mastery, educational work and innovation, all in service of an urge to share ideas and build musical communities.

Meyer’s acclaimed performances using a single loop pedal showcase her ability to craft imaginatively layered soundscapes, creating immersive and transformative musical experiences.

In addition to her work as a performer and educator, Meyer has been creating a unique compositional oeuvre over the past decade that ranges from pieces for solo viola (with and without electronics) and voice to music for chamber and orchestral ensembles.

’I feel my life has finally come full circle as both an artist and an educator’, says Meyer about the current season, which includes the New York City premiere on 5 December of her 2023 chamber work Spirits and Sinew. Inspired by the Voodoo ’healer, herbalist and entrepreneur’ Marie Laveau, who left her mark on 19th-century New Orleans, Spirits and Sinew is featured on a concert celebrating the 10th anniversary of the ensemble Hub New Music.

In October, the Auburn Symphony in Washington State gave the world premiere of Meyer’s fiery concert opener Turbulent Flames as part of her residency with the ensemble, launching a series of performances of the piece by regional orchestras across the US.

Additional world premieres by Meyer this season include Forces of Nature, written for the Exponential Ensemble; a new work for viola and piano for Juilliard’s pre-college commissioning initiative that is intended for emerging violists; and a setting for the Claremont Trio and tenor Paul Appleby of poetry about Manhattan’s Upper West Side by violinist and poet Giancarlo Latta.

Amidst her hectic schedule, Meyer took time to share insights about her inspirations as a composer, collaborative dynamics and the challenges and rewards of devoting herself to music that pushes the boundaries.

Your Spirits and Sinew is part of a programme of eight new works commissioned for Hub New Music’s tenth birthday (including contributions by such distinguished peers as Angélica Negrón, Tyshawn Sorey, Nico Muhly, Donnacha Dennehy, Marcos Balter, Sage Shurman and Andrew Norman). What made you swerve away from the path of the conventional performance career for which you had trained at Juilliard and start wanting to compose?

Jessica Meyer: I started the viola when I was nine and took to it very quickly. I always liked creating things and was encouraged to make up my own music in a music theory class I took in high school. One piece I created was a kind of little concerto for viola and computer that started getting attention. I knew that it tapped into a very specific part of myself. Later, I made it a focus of my educational work to get kids to pay attention to their creative choices by setting up classroom situations where they are making their own music.

The first time I heard an orchestra play ideas that I had helped facilitate in my educational work, there was an opening in my heart and I told myself: You need to do more of this. In 2012 or 2013, I started writing for myself using a looper pedal. [The earliest work Meyer lists, Duende from 2011, is for viola and looper pedal.] It gave me my training wheels as a composer. As soon as I heard a piece of chamber music I had written, I knew this is my calling. That was about ten years ago. Some 80-odd pieces later, here I am.

So you were able to reconnect with what you had intuited all along through your first creative efforts when starting out?

Jessica Meyer: I think that my ability to become a composer as fast as I did was because I spent a career playing with a lot of different people. As a member of the viola faculty at the Manhattan School of Music, I love training new performers and also teaching them about how to build a career in music. It’s about choosing yourself and what makes you your unique self, and how you build community in order to pave your own path.

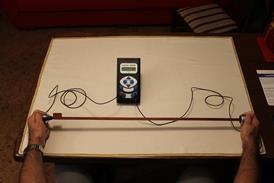

How did the looping technology help you when you started discovering your voice as a composer?

Jessica Meyer: I knew I was meant to go back to creating. And I knew I had a lot to express as a solo player, after many years being a cog in the machine. I commissioned some pieces for myself by other composers, but I wanted something that I could easily take around without having to worry about booking a lot of people – from the start, I was always thinking practically. At a festival in Brooklyn, I saw the comedian, beat boxer and singer Reggie Watts creating a whole performance with a loop pedal and decided I wanted to do that with my viola.

When I got a loop pedal for my birthday, I didn’t even read the instructions but just started playing and channelling my five-year-old self that would be drawn to any piano. But now I had this piece of technology that allowed a hands-free interaction. What was interesting to me was the challenge of how to make each piece sound different. I discovered many of the techniques I use to build ensemble when working with myself, like hocketing – these dense textures that slowly undulate and bloom over time — and then I took a lot of that into my orchestra music when writing for large ensemble.

Every performer I talked to who was thinking about writing their own stuff always wanted permission. I realised that you need to just go in your sandbox and start playing around with sounds. You know when something sounds good: keep it. If it needs to be massaged, then tweak it. It’s about trusting your instincts and knowing that there are no rules. At the same time, if you’ve performed enough music, you can make decisions about sound and proportion.

I realised that you need to just go in your sandbox and start playing around with sounds… It’s about trusting your instincts and knowing that there are no rules

You also play baroque viola and improvise with jazz musicians and composers from other traditions. How did improvisation become important for you?

Jessica Meyer: I was fortunate to have the jazz bassist Reynard Burns as my high school orchestra teacher. We were playing Turtle Island String Quartet arrangements where you had to stand up and take a solo when he pointed to you in the improv section. At Juilliard. I realised only a few of my colleagues had that kind of experience. I remember when I got out of the conservatory environment, which makes you hyperaware and perfectionistic, how hugely important it was to go back to improvisation and learn to trust myself again without putting such a tight filter on all my thoughts about what I’m playing. Improvisation is involved when I’m playing Mozart or Brahms, because my uniqueness as a performer guides the sounds to go in a certain direction.

Each commission you take on seems strikingly different from what you’ve done before. How did your ensemble piece Spirits and Sinew originate?

Jessica Meyer: When I have a commission from an ensemble or a vocalist, my first question is: are you wanting the groovy part of me or the contemporary classical part of me – or a little bit of both? Every commission has a different directive, and I write for what’s unique to the ensemble and to their strengths. Hub New Music is one of my favourite new music groups and has set out to create a whole body of repertoire for their unique instrumentation of flute, clarinet, violin and cello. I love that they’re not pigeonholing themselves into one particular style of new music but run the gamut. I knew that they can play anything and would be open to trying out very different colours and textures.

And as a composer, you yourself seem to move with ease among highly varied contexts, from pieces for solo viola to your recently premiered orchestral work Turbulent Flames.

Jessica Meyer: I just started writing a new piece for viola and piano commissioned by Juilliard’s pre-college division for faculty member Carol Rodland. I want to compose a functional piece that can be used for auditions and that sinks into the gorgeousness of the viola sound without trying to be like any other instrument – because a lot of our repertoire is still borrowed.

But I have to say that I’m also deeply excited about the orchestral stuff. I still remember my first youth orchestra rehearsal, when we played Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique. When I think of the orchestra, I think of the possibilities of power and colour and the feeling of everyone playing with abandon. I love every chance I get to do that.

Read: My tech set-up: violist Jessica Meyer

Listen: The Strad Podcast #112: making musical choices with violist and composer Jessica Meyer

Read: The Telegraph Quartet on performing live to a classic Buster Keaton silent film

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub.

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

The Canada Council of the Arts’ Musical Instrument Bank is 40 years old in 2025. This year’s calendar celebrates some its treasures, including four instruments by Antonio Stradivari and priceless works by Montagnana, Gagliano, Pressenda and David Tecchler.

No comments yet