Following a recent performance with the Buffalo Philharmonic, the cellist speaks about his journey to reconstruct and shine a light on the forgotten work by US composer Arthur Foote, which was written in the same year as the widely performed concerto by Dvořák

Read more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

My journey exploring the neglected works of America’s first generation of classical composers began when I heard the great André Watts perform Edward MacDowell’s Piano Concerto No. 2 (1885). I remember being enraptured by the work’s alternation of power and melancholy, yet also being stunned that I had never been exposed to it before. Written before Dvořák’s ‘New World’ symphony (1893), the first movement’s primary theme, in D minor, of the MacDowell concerto is almost identical to the primary theme of Dvořák’s fourth movement, which is only one step up, in E minor, but with more bombast. Might Dvořák have heard it in the 1890s? The next stop on my journey was listening to the performances by my father, Gerard Schwarz, of Arthur Foote’s Francesca da Rimini (1890)—maybe the most skillfully crafted American tone poem of the 19th century. Still a teenager, I was challenged to understand why I had never even heard Foote’s name, never mind this great orchestral masterpiece. Inspired by my father and Watts’ championing of the Second New England School (sometimes referred to as the ‘Boston Six’), I set out to see what works for cello lay dormant, waiting to be unearthed and brought back to life.

I was challenged to understand why I had never even heard Foote’s name

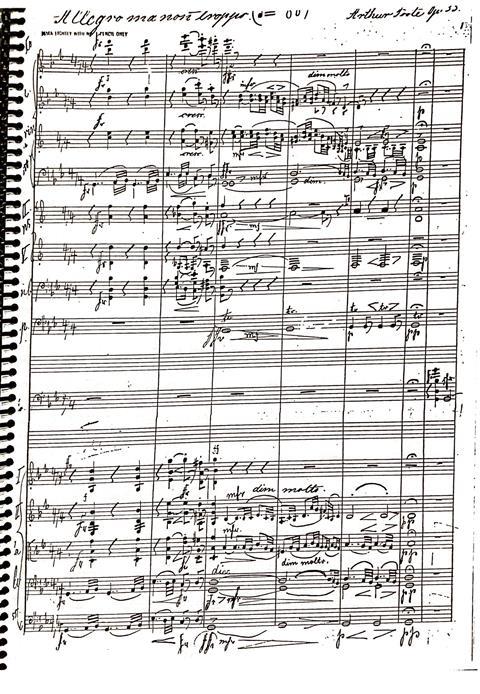

Looking through my father’s encyclopedia of American music, I came upon the complete listing of Arthur Foote’s output, including a Cello Concerto, Op. 33, in G minor. I looked online and in every record store—nothing. I looked for the solo part from every publisher—nothing. After contacting the librarians at the Seattle Symphony, I was told there was one set of hand-copied (handwritten) orchestral parts, including the orchestral score and solo part, available from The Free Library of Philadelphia—The Edwin A. Fleisher Music Collection. Intrigued by the scavenger hunt as well, the librarians in Seattle had the score and cello part shipped from Philadelphia. Copies were made and bound, and my next step was clear—find a way to play it. 15 years passed with not a single bite. I must have suggested the Foote concerto to conductors and orchestras dozens of times, usually receiving a response like ’Foote who?’ or ’our audience would prefer Dvořák.’ But why? I have heard musicologists claim that 19th-century American music was influenced so heavily by Western European harmony and counterpoint—with the composers having received their formal music education in Europe—that the music sounds unoriginal, lacking a true American sound (at least it seems Dvořák thought so as well, or did he?). But Foote was the first American composer to be entirely educated in the United States, and his unique style certainly sounds American to my ear. Maybe, I thought, it’s because Foote was a pious man, working as organist and music director at the First Unitarian Church in Boston for 32 years. Foote’s story lacked sex appeal, I rationalised.

As I encountered virtually no interest in his music, with neither a commercial recording nor an edition of the score readily available, I finally stopped trying. A few years later, after performing Amy Beach’s Piano Quintet (another Second New England School masterpiece) and Foote’s Second Piano Trio, in addition to revisiting my father’s Foote album on Naxos and stumbling across a Jorge Mester recording of Foote’s Francesca in my record collection, I began to revisit the idea. Here enters the great American conductor JoAnn Falletta. I have been lucky to work with JoAnn a handful of times with different orchestras, and I was able to bend her ear about the Foote concerto. As she, along with my father, are some of the few living American conductors who have actually championed great Americana of the past (not only focusing on new commissions), the project appealed to her. She was willing to allow me to come to Buffalo, perform it with the Philharmonic, and make the first commercial recording. As with many projects scheduled during the pandemic, the project was postponed multiple times for various reasons. Our performances on 23 and 24 March, 2024, were coming into focus, so I began to learn the work in January 2024. That coil-bound, photocopied, sun-bleached solo part and orchestral score, which had moved with me from apartment to apartment over the previous 18 years, were finally dusted off and placed on my music stand.

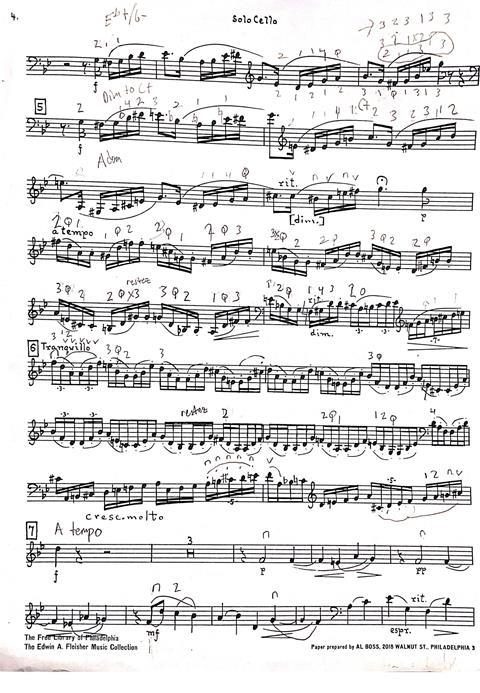

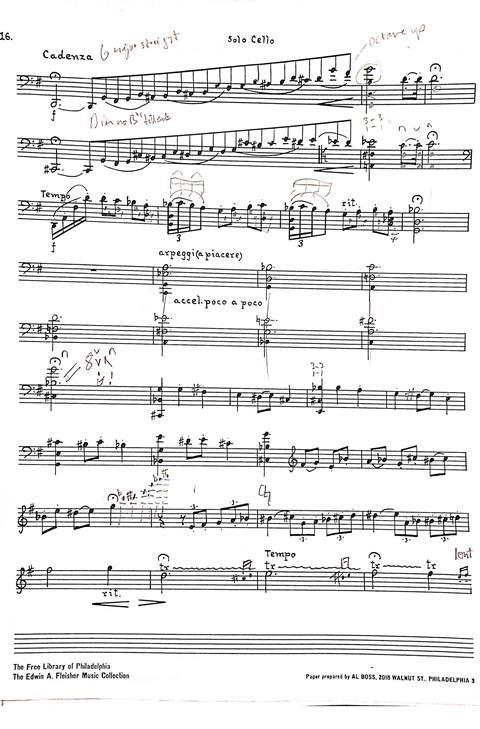

Though I had played through the work multiple times over the years, I had never edited the solo part (including fingerings, bowings, cadenza additions, register changes, phrase markings). My cello score indicated changes made by Foote and Bruno Steindel, the principal cellist of the Theodore Thomas Orchestra (later the Chicago Symphony Orchestra) and the soloist who premiered the work. (Interestingly, the conductor Theodore Thomas premiered both MacDowell’s Piano Concerto No. 2 and the Foote.) In the concerto, written the very same year as another great, pseudo-American concerto by Dvořák (1894), there are many extended cadenzas, which can take the form of the cellist/artist performing (think Kraft and Haydn, Wihan and Dvořák , Fitzenhagen and Tchaikovsky, Joachim and Brahms). This allowed me to be very free in creating virtuoso flourishes that fit well in my technique (for example, Tchaikovsky’s Rococo Variations features many passages of slurred staccato, a technique that was heavily favoured by Fitzenhagen).

Watch Julian Schwarz perform the above cadenza here:

After getting the cello part to a stage that both honoured the composer’s intentions and showcased my technical arsenal, my attention turned to the orchestral parts. The first step was to contact the Fleisher Collection to see if the orchestral parts were in good shape. Unfortunately, they were in disarray. It seems that a fine cellist, Douglas Moore, had resurrected the work in the 1980s and performed it several times. Even though the piece fell into obscurity for almost 100 years, Moore’s performances must have used those orchestral parts, which were hardly legible (a historic live recording of the concerto, performed by Moore, now exists on YouTube).

Luckily, I still had the photocopied orchestral score from all those years ago. Also handwritten, but clean enough to read. As my father was the conductor for our performances in Buffalo, he helped me establish a new, definitive edition of the work by engaging a copyist to input each orchestral part from the full score using engraving software, thus producing a full, publication-worthy set of orchestral parts. Even though music copying seems like a consistent task, it’s actually quite a painstaking and tedious process—each note individually entered in the computer—so we needed to check for various errata.

Just as the copying process was underway, my good friend Jonathan Pasternack, the artistic director of the Port Angeles Symphony in Washington, alerted me of a cello soloist cancellation for his upcoming symphonic week. I took this as a sign that the Foote was meant to have another performance before our recording. Even though we have rehearsals in Buffalo, it seemed risky to spend time fixing notes, harmonies, and other inconsistencies while also making a commercial recording. I was thrilled that Jonathan was courageous enough to take this work on, and I sped up my learning process to commit the piece to memory more than a month earlier than planned.

While working on the piece, Jonathan, the musicians of the Port Angeles Symphony, and I were all playing Sherlock Holmes—attempting to find every wrong note in each individual part. There were even whole bars missing that we had to revoice and handwrite into the score and orchestral parts. We reworked the ending of the piece to be more effective for the audience, and Jonathan established a long list of errata that were sent to the copyist for editing.

My journey with Arthur Foote’s concerto is far from over, as I will record the work and publish a new edition of the score for future generations of cellists and orchestras. An eager student of mine, who heard me practicing this unknown American gem, requested to learn the work as well. For now, he is working off my heavily-marked solo part, scanned from that facsimile I held onto as an eager youngster. If, by interpreting and championing this great music, playing it with passion and direction, I can bring it to its rightful place on concert stages nationwide, my teenage self will feel a great sense of nationalistic pride. I hope the work takes its place among the great American concertos, and that it will be championed by many who explore the music of the neglected Boston Six.

Listen: The Strad Podcast #113: Uncovering Ysaÿe’s lost works with violinist Philippe Graffin

Watch: ‘Bringing out a hidden love story’: Amit Peled performs a new arrangement of Dvořák Cello Concerto

Read more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

American collector David L. Fulton amassed one of the 20th century’s finest collections of stringed instruments. This year’s calendar pays tribute to some of these priceless treasures, including Yehudi Menuhin’s celebrated ‘Lord Wilton’ Guarneri, the Carlo Bergonzi once played by Fritz Kreisler, and four instruments by Antonio Stradivari.

No comments yet