La Serenissima director and violinist Adrian Chandler describes the process of resurrecting the unusual instrument in preparation for a series of performances

Viewed from a historical perspective, Vivaldi employed an extremely avant-garde approach to instrumental colour. One of the most unusual instruments to appear in his compositions was the violino intromba marina, a pimped-up violin for which Vivaldi himself may have provided the stimulus and which was intended to produce a sound not dissimilar to the tromba marina. This was a single-stringed instrument that can be traced back as early as the 12th century and which was still in use during the days of Mozart’s youth. It was commonly used in convent chapels as a substitute for brass instruments as it was deemed inappropriate for nuns to play trumpets. This explains the German nomenclatures Nonnentrompete (Nuns’ trumpet) and Marientrompete (Our Lady’s trumpet); it is probably from the latter that the Italians derived the term tromba marina.

The surviving evidence tends to suggest that the violino in tromba marina was unique to the Ospedale della PietÁ *. All the surviving music for this instrument was written by Vivaldi with the one exception of its inclusion in a Laudate pueri Dominum by Nicola Porpora composed when he was very briefly, Maestro di Coro at the PietÁ in 1741-2. The works in question by Vivaldi include three solo concertos; one concerto for two violini in tromba marina, two recorders, two chalumeaux, two mandolins, two theorbos and cello; and a recently discovered setting of a Nisi Dominus which uses the instrument in one movement.

More information concerning this instrument can be found in the account books of the PietÁ which record payments made to Matteo Sellas (who supplied quality instruments on Vivaldi’s demand to star pupils such as Anna Maria) for old violins (and also violas) to be fitted with tromba marina bridges and supplied with strings. Given that the PietÁ must have had a massive supply of standard gut strings for its orchestra, we can therefore assume that these strings were probably made of a different material not normally associated with stringed instruments and their playing techniques of the time. We have therefore opted for wire strings wound in brass (a common material used in harpsichord strings). Maybe it is no coincidence that the technique of producing wound strings had already been perfected in nearby Bologna during the 1660s and 1670s.

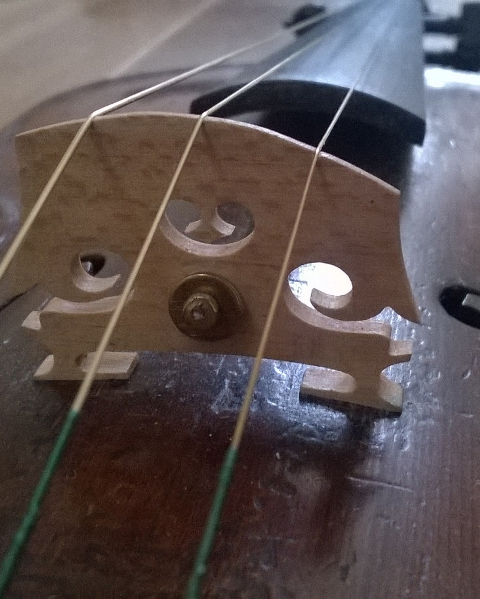

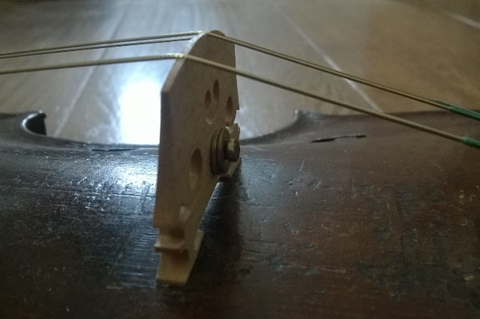

With regards to the specified tromba marina bridge, designed to carry a monochord, this cannot have been the solution used as if fitted, such a floating or hinged bridge would not have been able to vibrate in the way in which it was intended if more than one string was applied. Also, a brass bridge seems unlikely as this would impede the vibrations travelling down to the sound-post. In view of this conundrum, we therefore needed to find another way of producing the trumpet-like rasp of the tromba marina on our violin. Our first idea was to attach a metal plate onto the back of the bridge tied with gut but this was found to give somewhat inconsistent results and could sound simply like an open seam.

The solution to this problem was to replace the metal plate with a small, metal pin through the hole in the bridge, onto the back of which were placed two small rings whose purpose was to vibrate against each other giving a convincing tromba marina effect.

In order to reconstruct this instrument from such little evidence, we went back to Vivaldi’s scores to work out how we think this instrument sounded and then worked backwards to find our solutions. Judging by the regularity with which Vivaldi writes piano in the solo part (which is very unusual), we think that this instrument must have produced a very loud sound. This is further corroborated by the high incidence of double stops played by the soloist in the ritornelli passages. These passages are (as usual) doubled by the first violins (but without the double-stopping); if the solo instrument is not noticeably louder than the orchestral violins, this effect is lost. The countless piano markings that appear in the solo sections were probably intended therefore to instruct the soloist to ease off the volume, rather than play an actual piano.

Vivaldi scholar Michael Talbot, who has studied all the available evidence, furthermore has a hypothesis that this instrument had only three strings, tuned g-d’-a’. This of course would enable all of this repertoire to be played on a three-stringed viola (without a C-string) explaining the absence of music written for a ‘viola in tromba marina’. The three-string theory is amply supported by evidence found in the scores: chords played by the soloist never exhibit more than three notes; the highest note is b’’ (very unusual considering Vivaldi’s virtuosity); one passage played in double stops on the D and A strings is later repeated a fifth higher in single notes (due to the lack of an e-string); in the Nisi Dominus (RV 803) the violino in tromba marina dives down the octave in contrast to the ripieni violins who continue in a higher register on the e-string.

I have known about these concertos for over 20 years but have only recently seized on the opportunity to delve into the matter further, partly in order to balance a concert-programme and recording that La Serenissima are making of Le Quattro Stagioni to show the audience a part of Vivaldi that they really didn’t know before. With a composer of Vivaldi’s stature, it is not often that one finds oneself in a position to explore avenues that someone somewhere hasn’t explored before. To my knowledge the recreation of this instrument has not yet been attempted and so we are very fortunate to be the ones breaking this new ground for the first time.

We would like to thank Michael Talbot for his assistance on this project and also the luthier David Rattray who came up with all the practical solutions to our problems.

La Serenissima will be touring this project to the following venues:

17 April, Cadogan Hall, London

5 June, Aberdeen

13 June, Swansea

20 June, Stour, Kent

5 July, Harrogate

17 July, Oundle

22 July, Buxton

1 August, Petworth

11 September, The Sage, Gatehsead (tbc)

26 September, Cartmel Priory

17 October, Georgian Concert Society, Edinburgh

20 November, Bristol

21 November, Cambridge

15 January, Wigmore Hall, London

25 January, Malta

19 February, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester

20 May, Sheldonian Theatre, Oxford

For more information go to www.laserenissima.co.uk or www.davidrattrayviolins.co.uk© Adrian Chandler

*The Ospedale della PietÁ was one of four foundling hospitals situated in Venice, all of which were famous for the musical performances given by their female musicians who remained out of sight behind iron grilles. The other three were the Incurabili, the Mendicanti and the Ospedaletto. Vivaldi worked here at various times during his career, both as teacher and composer, even supplying conc

No comments yet