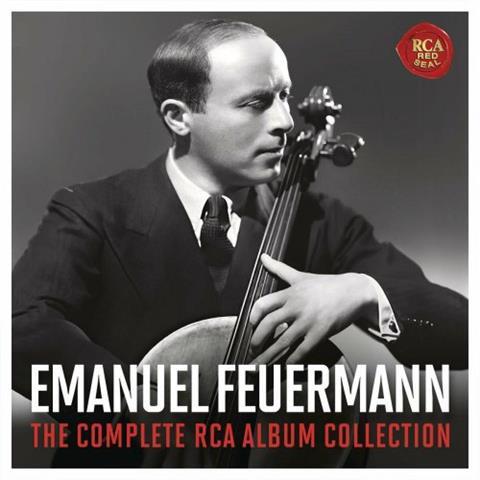

A first complete collection does justice to a cello legend

The Strad Issue: December 2024

Description: A first complete collection does justice to a cello legend

Musicians: Emanuel Feuermann (cello) Jascha Heifetz, Mischa Elman (violin) William Primrose (viola) Artur Rubinstein, Franz Rupp, Rudolf Serkin (piano) Hulda Lashanska (soprano) Philadelphia Orchestra/Eugene Ormandy, Leopold Stokowski

Works: Beethoven: Piano Trio op.97 ‘Archduke’; ‘Eyeglass’ Duo in E flat WoO32 (Allegro only); 12 Variations on ‘Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen’. Bloch: Schelomo. Brahms: Concerto for violin and cello; Piano Trio op.8. Chopin: Introduction and Polonaise brillante op.3. Dohnányi: Serenade for string trio. Mendelssohn: Cello Sonata no.2. Mozart: Divertimento for String Trio K563. Schubert: Piano Trio D898. Strauss: Don Quixote; works by Bach, Canteloube, Davidov, Fauré, Handel, Ochs and Schubert

Catalogue number: SONY CLASSICAL 19439977442 (7 CDs)

Medical bungling killed Emanuel Feuermann (1902–42) at 39, ironically the age at which Pablo Casals made his first discs. The younger man was recording a wide range of repertoire for RCA when he was snatched away.

The complete RCA 1939–41 78rpm recordings are in this fine box, presented in pochettes mimicking their LP issues. The remastering is the best so far accorded to this material: for the first time we hear Mozart’s E flat major Divertimento without distortion, although of course various types of surface noise come from the metal masters.

I first encountered Feuermann’s playing in 1967 via an LP of his Beethoven op.69 with Myra Hess and his nonpareil Schubert ‘Arpeggione’ with Gerald Moore, and I could not get his sound – that amazing, perfectly controlled vibrato – out of my head for days. Several of the recordings in this box formed my introductions to the works. I started my listening with one of those, Mendelssohn’s Second Sonata. The opening Allegro is like an eruption of joy; the Scherzo – with pianist Franz Rupp playing his full part – is truly fairy music with a lyrical Trio; the Adagio, in which Rupp rolls the chorale chords masterfully, is eloquent and Feuermann’s articulation in the finale is stupendous.

An advantage of six of these performances is that they enshrine some of Heifetz’s best playing. He could be controlling and coercive, but Feuermann was able to stand up to him, they had similar ideas on portamento and often meshed like twins. Brahms’s Double Concerto, well conducted by Ormandy, finds the soloists in complete accord – as much as Thibaud and Casals or the Busch brothers.

Read: Great cellists: Emanuel Feuermann

Watch: Cellist Emanuel Feuermann plays Dvorák and Popper

Read: ‘De Munck, Feuermann’ Stradivarius cello is loaned to Camille Thomas

Mozart’s Divertimento with Primrose is a lovely performance but the Dohnányi Serenade, with glowing tone from the violist, is even better. The movement included of the ‘Eyeglass’ Duo that Beethoven wrote for himself and his friend Zmeskal is bubbling entertainment.

Of the trios with Rubinstein and Heifetz, I like best the Brahms op.8, all three players at their most congenial. The Schubert finds Feuermann coaxing the Viennese style out of Heifetz and, although one always has Cortot, Thibaud and Casals in mind, this is lovely too. The ‘Archduke’ is also superbly played and paced, although some of Heifetz’s tone is too cosy for a composer he never, to my mind, came to terms with.

Don Quixote with Ormandy – and a fine Sancho from Samuel Lifschey – is a constant delight. I have seen his Schelomo with Stokowski described as overwrought, but surely it is that kind of piece? For me this uniquely confiding vocal performance, in which soloist and conductor are of one mind and EF appears to address God directly like a great cantor, matches Zara Nelsova’s 1949 recording with the composer.

Beethoven’s ‘Ein Mädchen’ Variations are debonair; Chopin’s Polonaise, spiced up by Feuermann, is a tour de force; Après un rêve is lovely, and there is an alternate take I almost prefer; Davidov’s At the fountain is astonishingly articulated; Canteloube’s Bourrée auvergnate features Feuermann’s cheeky upward glissandos; and the Handel and Bach arrangements, the latter previously unpublished, are nobly done.

Finally, two curiosities, Ochs’s Dank sei Dir, Herr, originally passed off as Handel, and Schubert’s Am Tage aller Seelen, rather stiffly sung by Hulda Lashanska with Elman, Feuermann and Serkin in support. An essential purchase for all who love the cello. The booklet is full of illustrations, but the note errs in saying he studied with Klengel in Vienna: it was Leipzig.

TULLY POTTER

No comments yet