Originally published in 2007 for the 50th anniversary of the composer’s death, this critical appraisal by Richard S. Ginell looks for the recordings that do justice to one of the best-loved works in the repertoire

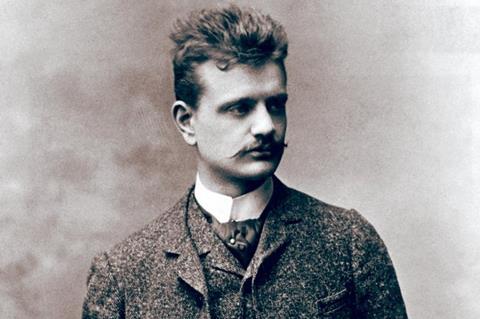

As we observe the 50th anniversary this month of the death of Jean Sibelius, his Violin Concerto in D minor op.47 is at the summit of the great concertos. It has succeeded in turning the ‘mighty four’ – Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Brahms and Tchaikovsky – into the mighty five. But it took a long time for the work to catch on in the 20th century, partly because Sibelius, himself a skilled violinist, gave fellow fiddlers a tough obstacle course. Even Jascha Heifetz – who in 1935, at the height of the Sibelius boom, was the first to record the concerto – couldn’t punch it into the repertoire. Perhaps Heifetz set such an unbelievably high standard that few dared to approach it. Indeed, it is possible to date the emergence of the Sibelius concerto into the standard repertoire from the point of Heifetz’s retirement in 1972.

Nowadays, with general technical standards at an all-time peak, almost everyone wants to play the Sibelius. The work seems to attract younger violinists in particular: it offers them numerous opportunities to flash their stuff. And conductors like it because there are many passages in which they and their orchestras can shine. The concerto also wears well because there is depth in the searching, brooding reflections of the icy Nordic landscape in the opening movement; because of the motoric rhythms that drive the outer movements; and because of the surging Romantic emotions of the climaxes in the second movement.

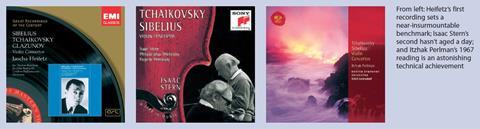

Yet 72 years on from the first recording, even as the performances on disc proliferate, Heifetz’s first recording still sets a near insurmountable benchmark. The concerto seems made-to-order for the Heifetz personality – the emotion shooting through every stroke that belied his impassive physical presence, the combination of what one critic called ‘fire and ice’ that suits this piece perfectly. Heifetz does indulge in a few portamentos, but there is not a hint of sentimentality. Thomas Beecham is propulsive and supportive, exploring the darkness of the orchestral writing as few others have since. Despite the less-than-full reproduction of the London Philharmonic Orchestra, there is still much to learn from this antique recording.

Heifetz’s first recording still sets a near insurmountable benchmark

Heifetz tried the Sibelius again in stereo in 1959, almost pulling off a second benchmark. Although his tone is a bit thinner and his technique not quite as impervious as in 1935 (nor is Walter Hendl’s conducting as imaginative as Beecham’s), Heifetz’s violin still sings, exults, blazes and dominates. For instance, on both recordings he second-guesses the composer by extending the finale’s last ascending scale to the G beyond the written E flat, presumably for bravura effect. The tempos in his second recording are probably the fastest on record, cutting a minute off his first. There are many collectors who swear by two early female Sibelius champions whose careers were cut short – one by choice to raise her family (Camilla Wicks) and the other by a plane crash (Ginette Neveu). But I find Neveu’s 1945 recording to be a sometimes tedious, slug-it-out, musically not-very-unified affair, with pedestrian conducting by Walter Susskind, lots of throbbing vibrato in the coda of the second movement and a rather deliberate finale as Neveu fights hard for each note. Wicks’s 1952 Stockholm session, reissued at last in 2006 after years in limbo, is more interesting. Her tone has a unique cry in the first movement’s opening bars, after which she strikes a good balance between a cool temperament, technical fireworks and, in the second movement, emotional involvement. Sixten Ehrling is dependable on the podium, but little more; and the sound is nothing special.

Ehrling turns up unobtrusively again in David Oistrakh’s earliest bout, with Sibelius in the West (1954), in which the violinist is already at the peak of his form. His tone is warm and emotional – without being over the top – in the second movement, and he gets more colour out of the first movement’s largamente cadenza than almost anyone. There are other, later Oistrakhs from Russia and the West in variable states of sound, but this one shows what a marvellously natural, balanced player he was.

Another superb mid-20th-century performance comes from Zino Francescatti, who sports a beautiful, aristocratic tone with a fiercely sweet upper register. He grabs tightly on to the big waltz-like secondary theme in the first movement, and brings the second movement to two huge emotional climaxes. Urging him on is the passionate Sibelian Leonard Bernstein, who hurtles the opening movement’s tempos along with irresistible nervous energy, lingers lovingly in the slow movement and plays the extrovert in the finale. Yet Heifetz’s most formidable competitor was Isaac Stern, who recorded the Sibelius twice. His first recording is in mono and from 1957, with Beecham again finding the heart of darkness, this time with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. The young Stern’s tone already burns: every note in the second statement of the first movement’s theme is underlined and branded into the score. But his second recording – in stereo with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1969 – is the great one. Stern is even more intense, more pointed, more rhythmically incisive in the outer movements, retaining and refining his total command over the sustained line in the second movement. The underappreciated Ormandy exploits his plush Philadelphia strings to the hilt yet always keeps things moving; he gets a terrific propulsive rhythm going in the finale, where at last the timpani can be clearly heard. Everyone in the session is digging in, and the sound is a miracle of balance; it hasn’t aged a day.

Stern is even more intense, more pointed, more rhythmically incisive in the outer movements

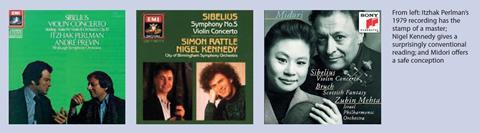

At this point we come to an informal divide in our survey: from here onwards the tempos used in this concerto generally get slower and slower. In Heifetz’s day the norm for a performance was anything from 26 to 29 minutes, against which Neveu and Wicks seem rather slow at around 31 minutes, 45 seconds. But today Neveu and Wicks would be at the fast end because timings have ballooned to between 32 and 34 minutes or more; no one in this survey since Stern in 1969 has brought it in under a half-hour. Indeed, Itzhak Perlman’s two recordings bridge the transition of tempo in this work. His 1967 recording – his debut on records – with the absolutely objective Erich Leinsdorf and the Boston Symphony Orchestra is an astonishing technical achievement, but a bit cold and brusque. All is different with Perlman, André Previn and the Pittsburgh in 1979, when the soloist took three and a half minutes longer to nail the solo part passionately and methodically, his sound now brightly lit and red-blooded, the warmth of his personality in full bloom. Previn aims for the dark side and gets there much of the time, keeping his soloist anchored to the rhythm as his brass buzzes menacingly in the finale. Whereas Perlman’s 1967 disc shows promise, the 1979 disc has the stamp of a master.

For a tempting budget price, Ida Haendel offers a meticulous, technically fit, leisurely paced performance that draws blood at the right moments. But despite Paavo Berglund’s firm, idiomatic control of rhythm, the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra does not play like a first-rate band. Salvatore Accardo also has a fine Sibelian on the podium, Colin Davis, who conjures a dark, timeless stillness that puts the music in a trance. Too much of a trance, it turns out, for after a while the journey becomes so drawn out that the listener loses interest. Accardo’s tone, so lovely and rich at the outset, soon turns raw and doesn’t fully recover.

Gidon Kremer is one of the few violinists who convey a real chill at the opening, brandishing a slender, silvery tone, an understated approach to the Romantic second movement, and an aversion to striking virtuoso poses. With Riccardo Muti directing the Berlin Philharmonic in stark, always vigorous, accompaniment, this issue eschews glamour and flash. Miriam Fried’s dark-horse contender from Finland, with the brooding Okko Kamu in charge of the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra, emerges as if from a dream. She continues to take her time throughout, her tone wiry and strong, and takes the trouble to observe Sibelius’s note values. Alas, whatever tension there is drains out of the performance well before the finale signs off. Nigel Kennedy’s conception of the Sibelius with Simon Rattle and the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra is surprisingly conventional, his violin recessed almost self-effacingly within the orchestra, broadening to the point of torpor at predictable places. Even though the performance clocks in at a faster than normal pace for today, it feels much slower (not a good sign).

Cho-Liang Lin makes the same slowdowns just before the twin passages of broken octaves in the first movement, bringing an otherwise propulsive conception to a dead halt. Elsewhere, Lin’s performance is cool, controlled and not very individual – and Esa-Pekka Salonen hasn’t yet taken the measure of the orchestral part. But he does get it in his later Los Angeles recording with Joshua Bell, the Finnish dark shading of the first movement now in hand, with lots of energy in the interludes and a firm rhythm in the finale. Bell starts out with a tone that seems to emerge out of a half-shadow; he is free with showy ‘soulful’ portamentos and rhapsodic cadenzas (you can hear him breathing heavily). Despite a few Bell excesses, this is one of the better recent versions. One can rule out Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg with Michael Tilson Thomas solely on the grounds of an unlistenable second movement, what with her weepy vibrato, gigantic portamentos in inappropriate spots, and high-anxiety climax that sounds like bad verismo opera. Julian Rachlin hears Sibelius only through Romantic ears – he is mannered in phrasing, laboured in tempo, and takes forever to get to the point. He’s accompanied by rich, lush Pittsburgh sonorities under the control of Lorin Maazel.

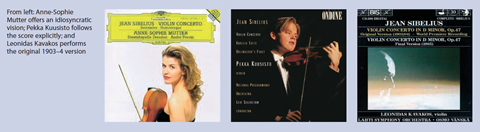

Midori offers a safe, generalised conception but at least she doesn’t annoy with distortions; she keeps things moving, handling the second movement with clarity and dignity while Zubin Mehta lays down his trademark homogeneous deep-pile carpet with the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra. Vadim Repin is another straightforward interpreter, with direct, technically brilliant but not hardedged attacks and smooth, sane trips to the summits of climaxes as conductor Emmanuel Krivine tosses all hints of personality aside. Repin is available only as part of a mammoth, though cheap, ten-disc set from Warner Classics. By contrast, Anne-Sophie Mutter has plenty to say – and she communicates her idiosyncratic vision while following Sibelius’s markings more closely than most. With Previn leaning on the Staatskapelle Dresden’s dark weight, Mutter’s opening notes peek through the night, leading to a sudden violent crescendo. Her arpeggios in the first movement get their full note values, and the coda has a revved-up life force. In the finale there is a fascinating war of wills – Previn setting down a firm rhythm and Mutter champing at the bit, wanting to run. You may disagree with this team, but you won’t be bored.

Anne-Sophie Mutter has plenty to say – and she communicates her idiosyncratic vision while following Sibelius’s markings more closely than most

Pekka Kuusisto also follows the score explicitly, sporting a tone with a slightly acidic, though pleasing, edge, singing but without resorting to sentimental tricks. Leif Segerstam and the Helsinki Philharmonic perform splendidly, with real understanding and understatement. Although the tempos are slowish, the breadth is backed by a sure rhythmic foundation, breathing authentic Finnish air. Maxim Vengerov may be the most gifted violinist of his generation – and I’ve heard him devour the Sibelius in live performance. Alas, his recording with Daniel Barenboim and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, however technically amazing, is too deliberate and calculated to have much effect. Vengerov gets off to a good start with a pristine tone that conveys the chill like a Siberian wind. But Barenboim’s granitic, Klemperer-like obstinacy ultimately gets in the way. Dmitri Sitkovetsky’s lovely full tone and heroic posture, coupled with Neville Marriner’s delineation of inner lines, sharp accents and rare clarity of texture, produce a first movement of imagination and promise, though the broadening tempos do not do much for the succeeding movements.

I’ve saved the most intriguing issue of the CD era till last. It’s a disc by Leonidas Kavakos and Sibelius cyclist Osmo Vänskä that pairs the familiar 1905 revised concerto with the hitherto-unrecorded original 1903-4 version that will come as a revelatory shock. The second movement is more or less unchanged, aside from a weird outburst of ghostly arpeggios near the close. But the outer movements are amazingly different, with familiar sections out of order, outbreaks of new material and a much busier orchestral backing for the soloist. About five minutes longer than the revised version, it is like seeing a familiar friend through the warped prism of a dream – and one has to agree that Sibelius was absolutely correct in pruning the piece. Kavakos and Vänskä have remarkably similar conceptions for both versions – slow, sometimes dragging tempos, subdued rhythm, the violin submerged within the orchestra. But Vänskä compensates by revealing detail that escapes others and making his Finnish brass snarl menacingly.

Of the historical recordings, I would choose Heifetz–Beecham, Francescatti– Bernstein and Stern–Ormandy; any of the three gives a thrilling experience, and the excellent sound of the Stern might tip the balance in its favour. Of the recent versions at slower tempos, Perlman–Previn and Kuusisto–Segerstam are the most satisfying, with Mutter–Previn the most interesting. Alone, the Kavakos–Vänskä performance of the revised version would not be a top recommendation, but coupled with the rare original it becomes a necessity for anyone who loves this work.

Please note these catalogue numbers are as printed in September 2007 and may no longer exist in this form

>> Salvatore Accardo, 1979

Philips 446 160-2, 2 cds

London Symphony Orchestra

Colin Davis

>> Joshua Bell, 1999

Sony sk 65949

Los Angeles Philharmonic

Esa-Pekka Salonen

>> Zino Francescatti, 1963

Sony s2k 63260, 2 cds

New York Philharmonic

Leonard Bernstein

>> Miriam Fried, 1987

Warner 0927 40606-2

Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra

Okko Kamu

>> Ida Haendel, 1975

EMI 5 75236 2

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra

Paavo Berglund

>> Jascha Heifetz, 1935

EMI Great Recordings of

the Century 61591

London Philharmonic Orchestra

Thomas Beecham

>> Jascha Heifetz, 1959

RCA 82876 66372 2

Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Walter Hendl

>> Leonidas Kavakos, 1991

BIS CD 500

Lahti Symphony Orchestra

Osmo Vänskä

>> Nigel Kennedy, 1987

EMI 7 54559 2

City of Birmingham

Symphony Orchestra

Simon Rattle

>> Gidon Kremer, 1983

EMI Seraphim 73561

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

Riccardo Muti

>> Pekka Kuusisto, 1996

Ondine Ode 878-2

Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra

Leif Segerstam

>> Cho-Liang Lin, 1987

Sony sk 92613

Philharmonia Orchestra

Esa-Pekka Salonen

>> Midori, 1993

Sony sk 58967

Israel Philharmonic Orchestra

Zubin Mehta

>> Anne-Sophie Mutter, 1995

Deutsche Grammophon 447 8952

Staatskapelle Dresden

André Previn

>> Ginette Neveu, 1945

EMI Great Recordings of

the Century 76831

Philharmonia Orchestra

Walter Susskind

>> David Oistrakh, 1954

Testament sbt 1032

Stockholm Festival Orchestra

Sixten Ehrling

>> Itzhak Perlman, 1967

RCA 82876 59419 2

Boston Symphony Orchestra

Erich Leinsdorf

>> Itzhak Perlman, 1979

EMI 5 62590 2

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra

André Previn

>> Julian Rachlin, 1992

Sony sb5k 87882, 5 cds

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra

Lorin Maazel

>> Vadim Repin, 1994

Warner 2564 63263-2, 10 cds

London Symphony Orchestra

Emmanuel Krivine

>> Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg,

1993

EMI 7 54855 2

London Symphony Orchestra

Michael Tilson Thomas

>> Dmitri Sitkovetsky, 1999

Hänssler 98.353

Academy of St Martin-in-the-Fields

Neville Marriner

>> Isaac Stern, 1951

Sony sm3k 45956, 3 cds

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

Thomas Beecham

>> Isaac Stern, 1969

Sony smk 66829

Philadelphia Orchestra

Eugene Ormandy

>> Maxim Vengerov, 1996

Warner 2564 63780-2, 11 cds

Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Daniel Barenboim

>> Camilla Wicks, 1952

Biddulph 80218

Stockholm Radio

Symphony Orchestra

Sixten Ehrling

2 Readers' comments