In the process of researching his book on Stradivari instruments, Toby Faber spoke to the British cellist about the powerful connection between a musician and his instrument

My original proposal for a book about Stradivari was to trace the story of five of his violins, and in so doing, address the central mystery associated with him: why are his string instruments still the best in the world, nearly three hundred years after his death?

My British publisher suggested I expand my remit to include a cello, however, which was a good idea. Stradivari made far fewer cellos than violins - the demand was not so great, the effort involved in making one was so much greater - but those from his golden period are even more sought after than his violins and they have terrific histories. I chose to follow the 1712 Davidov because I liked the way its life encompassed both its eponymous Russian owner and, more recently, Jacqueline du Pré and Yo Yo Ma.

Part of what I wanted my book to capture was the relationship between modern players and these amazing instruments, and although Ma was unavailable for interview, another Strad-playing cellist turned out to live just down the road. Appropriately enough Yehudi Menuhin’s son Jeremy made the introduction (one of the violins I was following was the 'Khevenhüller', Menuhin’s main instrument in the first part of his career), and so I met Steven Isserlis.

Steven could not have been more welcoming. At the time he was playing the 1730 'de Munck' Stradivari, lent to him by the Nippon Music Foundation. He told me how his heart leapt every day when he took it out of the case - ‘Its beautiful colour glows’ - and how this Strad was special in a way that no other cello was - ‘It can produce any tone colour that I think of.’ He let me touch it: my first experience of the wonderful openness with which these valuable objects are treated; they are not just museum pieces, but tools of the trade, meant to be handled. He told me of downsides too: waking to a weekly nightmare that he had left it on a train; the need to book two extra tickets for every flight (one for the cello itself, and one for a minder). And he told me of the practical benefit he drew from its previous ownership by the great Emanuel Feuermann; how when he first acquired the cello, he pursued adjustments until its clarity matched what he heard on a Feuermann recording. Most mysteriously of all, Steven recalled teaching a masterclass on Ernest Bloch’s Schelomo. ‘Before I remembered what cello I was playing, I thought “Hang on, my cello knows this†.’ No surprise there, perhaps: Feuermann was asked to perform Schelomo so often that he grew to hate the piece.

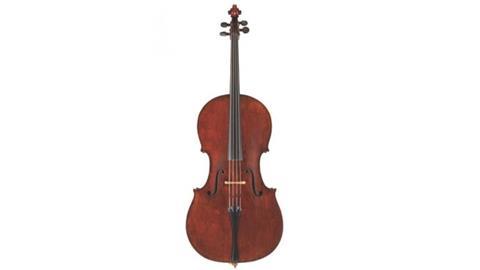

Steven returned the 'de Munck' in 2011 (it is now played by Danjulo Ishizaka) but in its place the Royal Academy of Music has lent him the 1726 'Marquis de Corberon' cello (pictured). This has a similarly rich history to the 'de Munck', with a provenance that includes Zara Nelsova. The RAM website places it among the last of the 20 surviving cellos that Stradivari constructed on his great ‘B’ (‘Buono’?) form mould. This is the internal template around which he would start making a cello, by bending and gluing in place the thin strips of hardwood which would form the ribs of the instrument. The dimensions of the template therefore govern the dimensions of the finished soundbox. Stradivari’s arrival at the ‘B’ form for the cello around 1707 marks the beginning of his golden period for the instrument. His earlier cellos were much larger, and tend to have been cut down for modern playing requirements.

By 1726 Stradivari would have been 82. The craftsmanship in his violins is beginning to show signs of age; it is likely that in order to complete the more physically demanding cellos he had substantial assistance from his sons, most probably Francesco, the oldest. Stradivari’s use of willow for the 'Marquis de Corberon'’s ribs and back (maple is usually preferred), and the large knot in its wood, are evidence of the workshop economising by using cheaper materials. In short, the golden period is coming to an end.

Nevertheless, these later instruments still have a beautiful tone. Steven’s website tells of the 'Marquis de Corberon'’s amazing warmth and particularly rich bass. How evident these sound qualities will be to the audience listening to Steven and pianist Olli Mustonen’s performance of Schumann, Kabalevsky and Prokofiev at the Tetbury Music Festival is uncertain. The truth is, probably not a lot. Members of an audience always find it hard to tell when they are hearing a Stradivari. Ninety-nine percent of what they experience is, of course, the talent of the player. But that’s the point. One person will certainly know that Steven is playing a Strad, and that person is Steven himself. The knowledge that he does not have to force the sound from his instrument, that it will respond to him, means that he can relax while he plays. That is the benefit the audience will derive, as we hear a great player playing a great instrument.

Toby Faber will be speaking at the Tetbury Music Festival at 3pm on Saturday 1 October 2016, before Steven Isserlis’s performance at 6.30pm the same evening. His book, Stradivarius: Five Violins, One Cello and a Genius, is published by Macmillan in e-book and paperback.

The 'Marquis de Corboron' is one of twelve stunning instruments featured in The Strad Calendar 2017: The Academies Collection, which celebrates the collections of conservatoires and music colleges around the world. For the complete list of instruments, and to order your copy today, click here

Watch Steven Isserlis performing Schumann's Cello Concerto on the 'Marquis de Corberon' Stradivari below:

Watch: Steven Isserlis on period instruments and his Stradivarius cello

Photo: Stradivari 1726 'Marquis de Corberon' cello © RAM/Ian Brearey

No comments yet