Violinist Hector Scott illustrates how employing Hogarthian principles of grace and beauty can help musicians explore physical and musical gestures from different perspectives

The 18th-century English painter, printmaker, pictorial satirist, social critic, and editorial cartoonist, William Hogarth (1697-1764) broke the mould of social commentary and ways of presenting moral issues to the public. His use of symbolism allowed his paintings to be ‘read’ almost like texts. It might be argued that Hogarth is Britain’s most influential visual artist, perfecting a new art form and devising his own, highly shaded visual language that was made for the people and was, while never fully recognised by the establishment, adored by the public.

He explored his ideas of artistic design in his book The Analysis of Beauty (1753) in which he defines the aesthetic principles of beauty and grace. As musicians, this book offers us insight in how we might create beauty through sound and allow music to be ‘read’ like a text. In hearing something we consider beautiful, the listener is not necessarily making a random choice but rather their decision making might be directly related to their complex nervous systems and mind. This idea is now supported by the findings of epigeneticists that suggest that one can inherit acquired traits.

This idea of acquired traits is explored by William Hogarth in his art. It also sheds light on how we can recognise beauty in music as well as offering solutions to solving such expressive complexities as to how we orientate our thinking in terms of interpreting the music we play. For Hogarth, ’sameness and strict regularity are to be avoided and modified by turnings, contrasts, and motion’ (Charles Davis). He describes the form of objects in terms of a surface corresponding to a shell of lines. Lines can be straight, curving, waving as in contrasting curves in a plane, and Serpentine as in waving and winding, or twisting, in space. The waving line he described as the ’line of beauty’. This can be clearly seen in the waving lines of Beethoven’s Violin Sonata op.23 second subject that contrast so dramatically to his first subject.

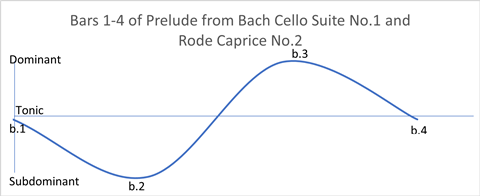

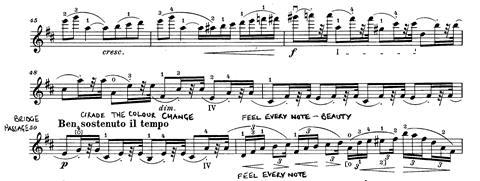

In finding meaning to the musical text, notice how the harmony in bars 1-4 of Bach’s Prelude from cello suite no.1 and Rode Caprice no.2 create the serpentine ‘line of grace’.

In emitting beauty owing to their being the most varied lines in form, the waving and serpentine line have the greatest impact on the promotion of beauty. For Hogarth, variety was composed, ’as without design, is confusion and deformity.’ The examples above also fit Hogarth’s idea that simplicity gives beauty to variety. In these examples it is simply the relationship between the use of tonic, subdominant and dominant harmony. To achieve variety, Hogarth describes the use of light, shade, colour, character, expression, and motion.

When we define our ability to change sound qualities, too often we focus on a two-dimensional vision of sound through the varied use of bow speed, bow pressure, point of contact, and bow tilt. This unfortunately limits the way we perceive and experience the feeling of projecting energy and the resulting texture of bow hair against string. Cubist painters such as Picasso and Braque wanted to emphasise that while a painting is a flat surface, the things they represented were three-dimensional. Interestingly, this was also Hogarth’s purpose in considering the variety of lines which form bodies in the mind, i.e. three-dimensional volumes.

Violin hanging on the wall by Pablo Picasso

Just as Cubism was a style geared to the modern world of speed and change, so it is now time for string training to transform and understand how we project energy. Looking at the world of drama training may offer new ideas in developing the physical connection throughout our body. Through the use of somatics we can learn to react to a musical stimulus by exploring with ‘a child’s sense of wonder’ stimulated movements. This exercise develops the connection further, by highlighting the importance of our breathing and opening our senses to the idea of texture.

When deciding on an appropriate texture we should imagine our movements through air (pushing dry ice), water (fluid with various viscosity), and fire (unpredictable, faster actions) with each new texture being organically arrived at through the previous movement. This ability to connect the energy we project in creating a sense of flow, is clearly seen in the transitional writing of Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto.

These ideas have such a strong connection to the use of the bow and feeling the hair against the string. It focuses the attention on how we draw the sound out of the instrument and leads to how we look at characterisation. We can apply the ideas of texture through internal and external expressivity (the power of eclosion – contracting and expanding like a butterfly emerging from the pupal case).

We learn how to think our ideas either out into the space, or in through an inward intimate focus. This placement of energy involves investigating the high and big movements of the external and the small, low movements of the internal but it also draws in the elements of timing, silence, and gesture (use of tempo, interpretation of rhythmic features, rhetorical gestures, rests, inflection and intent of sound).

By exploring these elements, we can enhance our story telling through experiencing our performance and physicality in a three-dimensional manner by hearing, seeing, and feeling our physical gestures from a different perspective.

Hector Scott is a former student of Max Rostal in Bern and Eric Rosenblith at New England Conservatory. He is associate head of strings at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland and was formerly head of strings at Marlborough College.

No comments yet