Alexi Kenney describes playing the 300-year-old 'Joachim-Ma' Stradivarius violin, on loan to him through the New England Conservatory

It’s been a couple of months since I received the 'Joachim-Ma' Stradivarius violin of 1714 on loan from New England Conservatory, where I am pursuing an Artist Diploma in violin. The instrument most recently belonged to the late Si-Hon Ma, a violinist and pedagogue who graduated with an Artist Diploma from NEC in the 1950s, and whose heirs recently gifted it to the school.

Antonio Stradivari’s instruments are incredibly valuable, priced in the multi-millions and occasionally rising into the eight digits. They are prized for a reason: throughout their 300-year history, they have been cherished, played, and respected by nearly every major violinist (Stradivari made many fewer violas and cellos, and those too are coveted). Perhaps the most famous violinist of the 19th century was another owner of this violin, Joseph Joachim, whose vast and staggeringly influential artistic circle of friends included Max Bruch, Frederic Chopin, Antonin Dvorák, Clara and Robert Schumann, and Johannes Brahms, who wrote his momentous Violin Concerto for Joachim. The Brahms Concerto was premiered on the violin I now play, on New Year’s Day 1879, with the composer himself conducting.

The only analogy I can think of between the sound of most other instruments and this Strad is with food (my second passion in life): it’s like sugar versus caramel. Though both are essentially the same ingredient, heat and time transforms sugar into caramel, a much richer, deeper, mysteriously layered, and complex world of flavour. It’s sweet, yes, but it has an undefinable quality, an almost savory umami, that takes it from simple to refined.

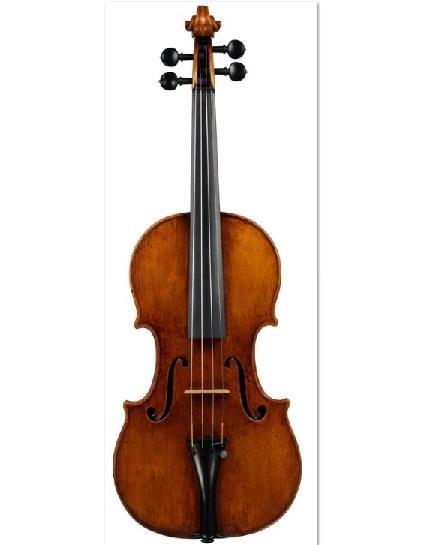

The Strad has umami. Layer upon layer of complexity exists within the sound, carrying with it darkness, depth, and a silken sweetness that doesn’t overpower. Beyond its exquisite sound, the appearance of the 'Joachim-Ma' is arrestingly beautiful. Made in Stradivari's Golden Period, so called because of the golden hue of the ground coat of varnish, its colors change depending on the angle and lighting, revealing hints of deep crimson and orange alongside the resplendent golden brown.

It is also remarkably well-maintained for being 300 years old, and I think part of that has to do with the respect for its provenance. The more I think and fantasise about where this violin has been, the more I am in awe of what I have in my hands. It's mind-boggling to think that when Joachim was working with Brahms on the solo part of his Concerto (which we know was heavily influenced by Joachim’s playing style and technique), the sound of this violin most likely played a big part. The instrument was Joachim’s for over 30 years, having acquired it at the age of 18, and with it in hand he first made a name for himself. I’m currently working on Schubert’s Octet here at the Marlboro Music Festival, and it is fun to speculate that perhaps this piece would have been played on this violin by Joachim in one of its first performances. The same can be said of Bach’s Sonatas and Partitas for solo violin, which Joachim was single-handedly responsible for reviving as they had fallen into obscurity in the hundred years after Bach’s death. Nowadays they form the most important pillar of our repertoire.

It’s been a joy to discover this violin’s sweet spots (there are many), and I’m especially excited to be playing my first Brahms Concerto on it this September with the Santa Fe Symphony. They say violins carry with them the souls of their previous owners and players — maybe it’s Joachim’s heart that I hear in it. And who knows, maybe he was a foodie too.

Read: New England Conservatory receives ‘Joachim-Ma’ Stradivarius violin from Si-Hon Ma estate

Read: Violinists Tessa Lark and Alexi Kenney receive 2016 Avery Fisher Career Grants, worth $25,000

No comments yet