The great Russian violinist and teacher Nelli Shkolnikova’s principles of violin technique

Nelli Shkolnikova performing at the Moscow Conservatoire

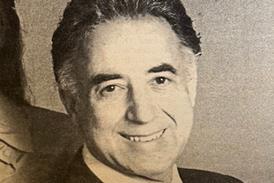

For the twelfth and final quote in our festive series from The Strad archive, we end as we began: with words of advice and experience from a great female violinist, this time the Russian Nelli Shkolnikova (1928-2010), remembered by her former student Curt Thompson

‘Tightness is the worst enemy for everything. When I say play in a natural way, it shouldn’t be like cotton. No, it’s alive, but you have to know which muscles are involved in a certain skill; all others should be absolutely uninvolved.’

‘Everything I teach, this work on scales, on etudes and exercises, should not be done mechanically, but rather focused on the result in sound.’

‘The most important quality is cantilena, because everything is like the human voice. Even technique should be singing, and not just with a dry sound.’

‘When you are practising by yourself, there is no teacher to tell you, This is good or That is not. You are your own teacher, and you have to try to develop. It’s a matter of concentration. You have to know what you would like to do, how it should sound, and then try to play like that.’

‘The movement of the fingers should be the same in any tempo. For example, when people play slowly, sometimes they lift and drop very slowly. This is wrong. One should lift a little bit higher in slow tempo and a little lower in fast tempo, and when one lifts, it should be immediately loose.’

‘It takes many, many years to develop a professional violinist, and from the beginning it should be done right. One has to be patient, without jumping forward too quickly. The skills are accumulated gradually. It might take a little longer to achieve, but it will not bring tightness and frustration.’

‘Some people play like on a piano with only one finger down at the time. You have to eliminate any additional tension. If a finger is relaxed, it wants to drop by itself. At least two fingers should nearly always be down simultaneously and every single movement should be carefully watched by the teacher.’

Like Yankelevich, Shkolnikova believed that it was necessary to master technique through the study of etudes rather than through pieces: ‘Etudes can be a little more diffcult than a student can achieve because through working on them, students will develop specific skills. But pieces and concertos should be less difficult because attention should be paid to musical and artistic tasks. The student should possess all skills necessary to play a given piece well. Some teachers believe that if they give a student a more difficult piece than they can achieve then it will help them develop. This is wrong. Most of the time it works just the opposite. They get tight because they’re not happy with how it sounds.’ She recalled that Yankelevich said of the latter approach: It is the way to the grave.’

To read the full feature published in The Strad September 2010, click here to log in or subscribe. Download the issue on desktop computer or through The Strad App.

Read: Thomas Demenga on ornamentation in Bach’s Cello Suites

No comments yet