In an article from 2009, Carla Shapreau exposes the systematic theft of stringed instruments under Hitler's rule, and today's efforts to locate them

Discover more lutherie articles here

In June this year, the international community met at a European Union conference in Prague to address unresolved issues from the Nazi era. The participants included 47 country delegations, 148 organisations, and a representative of the Holy See. One of the many subjects discussed was the loss of valuable musical instruments, manuscripts, printed music and other musical items that were confiscated, looted or swept up as war trophies during or after the Nazi era. Violins, violas, cellos and bows were among the many losses.

A number of factors have contributed to renewed interest in the history and fate of cultural property (including musical instruments) plundered or displaced during the Third Reich. These include the opening of World War II-era archives, the end of the cold war and Soviet communism, the aging of survivors, and the establishment in 1998 of the Washington Conference Principles pertaining to Nazi-confiscated art. These non-binding principles outlined the steps to be taken by 44 participating countries in order to identify and return property confiscated during the Nazi era to its rightful owners or heirs.

As a result, there has been an evolution in the ethical and legal standards applied to transactions in fine art, with particular scrutiny focused on provenance in the period 1933–45. Yet the musical world has lagged behind in both the mining of records and historical analysis.

There are many reasons for this, chief among them the fact that the dispersal, scarcity and, in some cases, inaccessibility of archival records pertaining to musical items has inhibited a thorough examination of losses during the Nazi era and its aftermath.In some cases, records contain only partial evidence, and following up leads is difficult because few witnesses remain.

Instruments of the violin family are by nature utilitarian and portable, which contributes to the challenge of tracking them down. Moreover, musical losses often accrued to individual musicians who may have only owned one instrument and who may not have maintained records or photographs for title and authentication purposes.

This story begins in early 1933, when life in Germany began to unravel for musicians, composers, conductors, music publishers and others in the musical sphere who found themselves at odds with Reich policy because of their race, ethnicity, or religious, political, social or aesthetic views. By March of that year, musical performances were being cancelled and some musicians were being ousted from employment. These events so shocked the music world that conductor Arturo Toscanini, along with other prominent musicians, sent a cable to Hitler in protest on 1 April 1933.

Against this backdrop, the legal framework in Germany was quickly changing, directly impacting the musical community. On 7 April 1933, a law was passed compelling the loss of employment for most civil servants of non-Aryan origin. Two days later, the New York Times remarked, ‘This edict is of far reaching significance in Germany, where all the leading theatres, operas and orchestras are either government-owned or supported out of the public exchequer.’ American composer Roger Sessions, in Berlin at the time, said that by June 1933, ‘there was not an opera house in Germany that had not been adversely affected by the ousting of Jewish conductors and musicians.’

On 22 September 1933 Joseph Goebbels, Reichsminister of propaganda, established the Reichskulturkammer (Reich Culture Chamber) in order to control the many facets of culture. By 1 November 1933 the law made it compulsory for professional musicians to register with its music division, the Reichsmusikkammer. Aryan ancestry was required.

In response to the exclusion of Jews from German cultural life, the Jüdische Kulturbund (Jewish Culture Association) was established in mid-1933, providing segregated and regulated venues for Jewish culture, including music. By 1937 it had approximately 180,000 members, including performers and audiences.

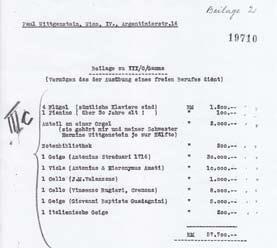

A decree by the Nazi regime issued on 26 April 1938 required Jews residing within the Reich to register their property if their assets exceeded 5,000 Reichsmarks. Austrian concert pianist Paul Wittgenstein was among the many who had to comply with this order (see below for an excerpt of his asset declaration).

In some cases, confiscation of musical effects took place soon afterwards. However, records from the Wittgenstein estate indicate that the pianist emigrated to the US with the Guadagnini and 1716 Stradivari violins, the 1620 Amati viola and the 1692 Vincenzo Rugeri cello.

Although numerous musicians were able to emigrate safely to other countries with their instruments, others did not overcome the significant administrative, legal and economic barriers to freedom. Quota limitations, required affidavits of support, burdensome emigration taxes, and restrictions on the transfer of assets and other property restricted free movement. The Third Reich closed the Kulturbund on 1 September 1941 after eight years of existence.

Shortly thereafter, Kulturbund musicians were ordered to surrender their instruments. The German borders were closed to Jews on 23 October 1941 and widespread deportations commenced. The eleventh decree to the Reich Citizenship Law of 25 November 1941 resulted in additional appropriations of moveable property by the state.

In tandem with confiscations within Germany, in July 1940 the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), a Nazi task force led by Alfred Rosenberg, commenced its organised and systematic approach to cultural plunder in territories occupied by the Reich. The division of the ERR charged with musical confiscations was known as the Sonderstab Musik and among its spoils were many instruments of the violin family. Musical looting was also carried out through Möbel Aktion, a division of the ERR, established by Rosenberg and approved by Hitler on 31 December 1941. This involved the seizure of the contents of homes of those who had fled or been deported. In Paris alone, the contents of approximately 38,000 homes were looted. A description of the ERR’s activity in France, the Netherlands and Belgium are the subject of Willem de Vries’s book, Sonderstab Musik, Music Confiscations by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg Under the Nazi Occupation of Western Europe.

Evidence of musical plunder and displacements has survived in scattered archives and in public and private collections. Preliminary research has revealed many disturbing clues that warrant further investigation. The continued pursuit of detailed evidence of the provenance of instruments through sources including Allied and Nazi wartime records, post war claims, reports and restitution materials, testimonies of those who did not survive, and of those who did, as well as other materials, is resulting in a growing body of information from which pieces of many puzzles will hopefully coalesce.

At present, the vacuum of publicly available information on Nazi plunder has left room for comments such as this one by Toby Faber in his book Stradivari’s Genius: Five Violins, One Cello, and Three Centuries of Enduring Perfection:

‘Yet it is hard to find an instance of a single Strad being lost in the whole course of the hostilities. There are rumors of them being stolen from continental Jews, and plaintive accounts still circulate on the Internet of family heirlooms being confiscated at customs during postwar flights from Eastern Europe. Every story adds to Stradivari’s mystique – to the possibility that a violin found bearing his label may, after all, be genuine. No account, however, is verifiable, and no famous Strad’s history comes to an abrupt halt during the war.’

Contrary to these assertions, historical research reveals evidence of several possible Stradivari instruments that went missing during World War II and remain lost. One such instrument is an alleged 1719 Stradivari that was stolen from the National Museum in Warsaw, Poland, during World War II.

It was referred to as the ‘Lauterbach’ Stradivari by W.E. Hill & Sons in their book Antonio Stradivari, His Life and Work after its purchase in 1900 by Henryk Grohmann. After Grohmann’s death in March 1939, his executors transferred the Stradivari, a Richert violin and three bows (one referred to as a Tourte and another engraved in gold and decorated with a diamond, said to have come from Tsar Nicholas II of Russia) to the museum. After the Nazi invasion of Poland in September 1939, Bohdan Marconi, chief conservator of the Warsaw Museum, hid Grohmann’s instruments in a double mahogany Hills case behind a wall ‘under the stairway in the Church Hall, First Pavilion’, and sealed the opening, according to a statement Marconi made to Polish government officials.

By the end of the Warsaw Uprising in 1944, the Stradivari’s hiding place had been discovered and the instruments had vanished, with the exception of one broken bow. US military records confirm that in September 1948, the missing Polish Stradivari was found by Officer Stefan P. Munsing of the US Army, in the home of a former SS member, Theodor Blank, in Heinrichsthal, Germany.

After an investigation, the following items were taken into US custody for restitution to Poland: ‘One violin (Stradivarius), one box, two violin bows.’ By October of 1948, records state: ‘The famous violin x already closed in Hesse’, suggesting that the investigation had run its full course, resulting in the return of the violin to Poland. But the Polish Ministry of Culture stated in 2008, ‘Our research has revealed that the Stradivari violin from the National Museum of Warsaw had never been returned to Poland.’ No photographs of the 1719 Polish Stradivari have yet been found and its current whereabouts remain unknown.

Additional musical losses occurred on Polish soil as well. For example, in the Lódz ghetto, where approximately 200,000 Jews from Germany, Austria, Poland, Czechoslovakia and Luxembourg, as well as 5,000 Roma, were sent, a decree was issued on 17 January 1944 requiring the ‘populace of the ghetto to surrender all musical instruments in its possession at the secretariat of the Chairman, 1 Dworska Street’. It was reported that ‘a number of high-ranking violin virtuosos’ were interned in Lódz and photographs confirm that many violin family instruments were among those surrendered in the ghetto. Several post-war claims indicate additional Polish losses, such as Kazimierz Moszkowski’s report that his alleged 1741 Guarneri ‘del Gesù’ and 1705 Stradivari violins and his 1604 Brothers Amati cello were stolen from him in Warsaw after the Nazi invasion.

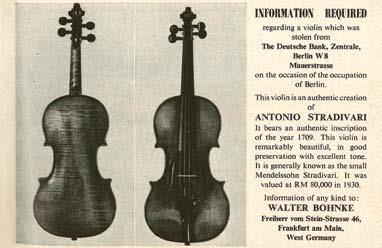

In Germany, a descendant of the Mendelssohn family reported as stolen a violin identified as a 1709 Stradivari. The violin was stored in a safe at the Deutschen Bank on Mauserstrasse, Berlin, in 1945 and remains missing war booty.

The case of an alleged 1719 Stradivari, taken from the Universität der Künste Berlin, the successor entity to the Hochschule für Musik, is more complex. The university reported the wartime loss of the violin, which is said to have been bequeathed to the school on 27 March 1943 by Dr Maria Alois Lautenschlager. During World War II, violinist and professor Gustav Havemann, then living near Berlin, took custody of the violin for safekeeping. But he found himself in the Russian zone at the end of the war, and turned the Stradivari over to two Russian officers.

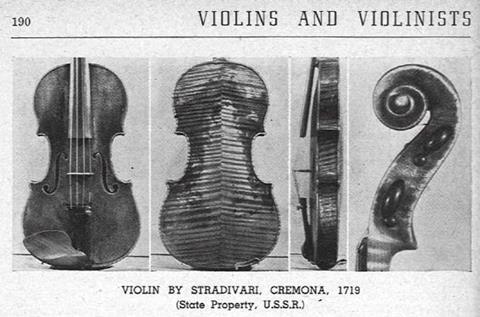

The Russian National Collection of Musical Instruments in Moscow has in its possession a 1719 Stradivari violin (inventory number 462) with an accession date of 1946, which appears to be a possible match with the missing ‘Lautenschlager’ Stradivari. Russian virtuoso David Oistrakh borrowed this instrument for a concert tour in 1949.

He made a stop in Budapest during the tour and Hungarian violin maker Laszlo Remenyi was able to take detailed photographs of the violin, the only known images of it to date. They can be seen in a 1949 article on the instrument by Ernest N. Doring in Violins and Violinists.

In the Netherlands, post-war loss reports were prepared by claimants, and they include many references to instruments of the violin family. A summary of these losses appears in the chart on page 37.

One such violin is reported to have been a 1783 Giovanni Battista Guadagnini made in Turin, which ‘was originally in the collection of a Jew in the Netherlands who was killed’, according to US military records dated 16 August 1948.

A couple with the surname Bleier, from Stuttgart, had purchased this violin in the Netherlands for 12,000 guilders and they were trying to obtain clear title. The violin was reported in Dutch records to have been ‘removed by act of force and in existence at the time of the German occupation’. A US military internal memorandum further stated that the ‘person who sold it to Herr Bleier presumably acquired it under suspicious circumstances’. The identity of the original Dutch owner, the violin’s current whereabouts and its authenticity are the subject of ongoing research. The Guadagnini was accompanied by a certificate of authenticity prepared by Parisian dealers Maucotel & Deschamps, which if found may provide helpful information.

Records from eastern Europe indicate similar musical losses. For example, in former Czechoslovakia alone, the Jewish populace in Prague was ordered by the Reichsprotektor to surrender all moveable musical instruments by 26 December 1941. Larger instruments, such as pianos, were taken from deportees’ homes. By February 1944 the number of confiscated musical instruments surrendered by deportees in Prague had reached 20,301. Significant musical losses have also been reported in France, Italy and other countries, all of which are the subject of ongoing investigation. For each instrument the issue of authentication is essential to the loss analysis.

After the war, Allied military units discovered stores of plundered property in castles, mines, barns, intercepted trains, bank vaults, air raid bunkers, church steeples and other caches. By 1948, the US government reported that ‘US forces had found approximately 1,500 repositories of art and cultural objects in Germany. These repositories contained approximately 10.7 million objects worth an estimated $5 billion.’

These figures do not distinguish between looted property and objects displaced during the war. Property described as displaced includes items from German collections, public and private, that had been evacuated to countryside locations to avoid damage from Allied bombing.

Some of these items vanished from these caches, taken as war trophies by the invading Red Army and others. In other instances, lost and looted property was found and returned to the presumed country of origin, if this could be determined. It was then up to the recipient country to return restituted property to the rightful owner or heirs if any existed. In some cases, post-war reports of musical losses were made by survivors or their heirs in an effort to discover the whereabouts of missing property.

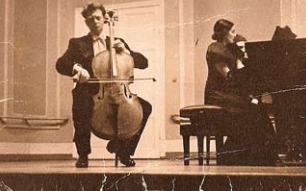

For many, the challenges of putting their lives back together took precedence. Dispersal of records and a lack of archival access contributed to difficulties in finding lost violins, violas cellos or bows. This was the case for German cellist Lev Aronson, a Holocaust survivor, from whose apartment in Riga his Bechstein concert grand, cellos allegedly made by Nicolò Amati and Mathias Neuner, and Tourte and Lamy bows were confiscated in 1941, discussed by Frances Brent in The Lost Cellos of Lev Aronson. His repeated attempts to recover his instruments were unsuccessful. Aronson reflected in 1986 at the age of 74, ‘I am convinced that somewhere in Germany or Austria someone is playing that priceless Amati cello and Tourte bow.’

Now that 70 years have passed since the start of World War II, it is tempting to leave the past behind. But the truth, whatever it may be, has a buoyancy, fuelled in part by memories such as those of cellist Anita Lasker Wallfisch. An Auschwitz orchestra member and survivor of the camp who is now in her 80s, Wallfisch said of her still-missing instrument: ‘I had once been the proud owner of a beautiful cello made by Ventapane. God knows who plays on it now.’

No comments yet