After twelve years as a concertmaster the artist switched to conducting and turned his back on playing for ever

Now in his late eighties, Anshel Brusilow studied conducting with Pierre Monteux for ten years from the age of 16, and in the same period performed as a professional violinist. After twelve years as a concertmaster, watching George Szell at the Cleveland Orchestra and then Eugene Ormandy at the Philadelphia Orchestra, he switched to conducting and turned his back on playing for ever. He was the Dallas Symphony Orchestra’s music director from 1970–73 and taught orchestral studies in North Texas from 1979 to 2008.

In my experience many musicians, especially string players, think about pursuing a career as a conductor because it looks easier than what they’re currently doing. They don’t realise how tremendously complicated it is. As an instrumentalist, you’re in complete control, musically, technically and otherwise. As a conductor, you have to know the orchestra, know how to read a score, know the problems that you know are going to be there, and know how to explain them. In truth, standing there and conducting the orchestra is the easiest part of the job.

When I decided to leave the Philadelphia Orchestra in order to conduct full-time, Eugene Ormandy asked me, ‘Why do you need that headache? You have everything!’ I told him that I had to do it. My opinion is that you can’t be both a conductor and an instrumentalist; it has to be either one or the other.

When you’re working with a soloist on a violin concerto, it helps greatly if you’re a violinist yourself. Not only do you know the instrument well, you can read the soloist’s movements more effectively. For instance, you shouldn’t be waiting for the violinist to tell you when to go on to the next bar. You have to take the lead in that, and you can do that by watching the bow. It’s got to end, it’s got to return, which means the next note or the next beat. It’s the same when it gets to the frog. For a solo pianist, you should move the podium so it’s partly at an angle, so that if you stand at the end of the podium, you can see the keyboard. Then you can anticipate by listening and watching the pianist’s hands. This was a trick I learnt from Ormandy.

I once met Stravinsky in Ann Arbor and asked him to autograph my score of The Rite of Spring. I mentioned that I was about to conduct it and he said, ‘Then make sure you conduct it the way I wrote it, because most conductors are frauds! They change the metres to suit themselves, so all they have to do is conduct it in 4, 3, 2, and so on. That’s not my music!’ I still notice that he’s right, in too many instances.

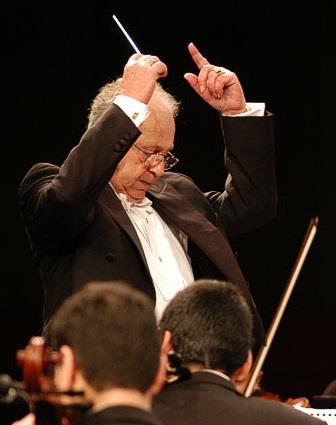

Photo: Brusilow with the University of North Texas Symphony Orchestra in 2008

Read Joshua Bell's interview on the art of conducting.

The Strad’s March 2015 issue, out now, investigates the increasing number of string players who are expanding their horizons – and musical skills – by turning to conducting.

Subscribe to The Strad or download our digital edition as part of a 30-day free trial. To purchase single issues click here.

No comments yet