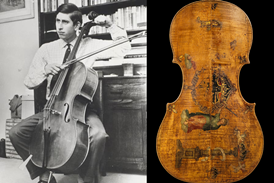

Yankelevich believed that violin playing is based on key physiological principles. In preparing the English translation of his works, Masha Lankovsky takes a look at some of his suggestions

Many great pedagogues have observed that one should play with the ‘head† and not with the ‘hands’, but consciousness goes beyond just understanding the purpose and nature of the movements we make. Being conscious also means understanding the neurological connections between our inner ear and our muscles, and the role of our conditional reflexes.

This is precisely the basis of the pedagogical writings by the esteemed violin teacher Yuri Yankelevich. In his work ‘Shifting Positions in Musical Context’ Yankelevich analyses every type of shift in order to discover the most efficient techniques. He arrives at the conclusion that every technique must be active, dynamic and adaptable so that it may accommodate the multitude of possibilities that musical interpretation requires.

Because of the difficulties in playing an instrument we often are quick to look for ready-made solutions – we are constantly searching for the ‘perfect setup’ or various ‘tips’ and ‘shortcuts’ to make our life easier. However, in order to achieve complete freedom in mastering the instrument it is much more effective to activate the appropriate conditional reflexes that correspond to what we need in the long run. This means creating an uninterrupted pathway between musical thought (‘pre-hearing’ the music in our head), the movement of our muscles, and the resulting sound that is verified and regulated by our ear. If these pathways are developed from the beginning, we are better equipped to adapt to all the subtle nuances that artistry requires.

For example, Yankelevich doesn’t support the use of any ‘helpful’ devices that appear to accelerate the learning process, such as marking the fingerboard or making contact with the body of the violin to feel more secure in third position. The problem with these devices is that they fixate alternate conditional reflexes that later need to be unlearned. It is natural for us to look for ways to simplify a difficult task, but in doing so it is important to constantly retain the connection between what we hear and the movements we make, since it is precisely this connection that allows us to develop as musicians.

One important reflex that needs to be developed is the relationship between vertical and horizontal movement in the left hand. Yankelevich believes that beginners usually spend far too much time playing in first position. If the student gets used to the left hand only making a vertical movement (ie, dropping the fingers onto the string) then the corresponding reflex is fixated and it becomes more difficult for the student to move horizontally. This may cause problems in shifting that can take years to overcome.

In order to activate the appropriate reflexes for horizontal movement, Yankelevich suggests the following exercise that a student can play even before learning the positions:

The right hand plays open strings, rhythmically dividing the bow into four or six quarter notes (quarter note = 40mm). At the same time the left hand moves along the fingerboard with the same rhythmic pulse, shifting between first and third positions.

This relatively simple exercise allows the student to realise that both the right and left hands are in constant motion, thereby developing the corresponding reflexes.

Yankelevich also advises against practising scales with just one specific fingering. Carl Flesch recommends learning scales with one fingering because this seemingly facilitates sight-reading – the idea is that one fingering establishes the corresponding conditional reflexes and then the memorised movements are instantly summoned just by glancing at a similar sequence. But, as Yankelevich points out, the problem with this approach is that it is impossible to foresee every possibility that might be encountered, and if the context changes ever so slightly a new fingering is required. This means the player is confronted with the additional problem of cancelling what is already entrenched and sight-reading actually becomes more difficult.

Yankelevich suggests an alternate approach that develops the quickest motor reaction to visual and aural perceptions. He recommends studying scales with different fingerings to activate flexibility and speed in the motor reflexes. He describes the following useful exercise devised by his teacher, Abraham Yampolsky:

Start from any note (say, A, for example) and try to play descending scales in different keys (for example: B-flat major, D major, D minor, etc.)

This is a great exercise to activate the quick reflexes that are needed for sight-reading. If we want to be free as creative artist-musicians, we must be in possession of a free and adaptable technique.

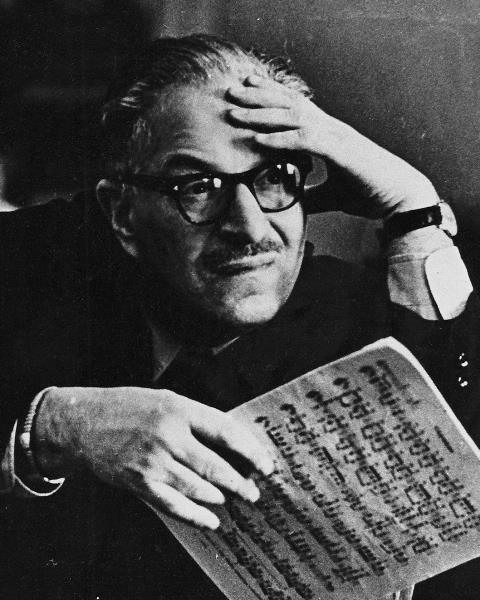

Yuri Yankelevich was one of the leading Russian violin teachers of the 20th Century, with 40 of his students winning first prizes in international competitions.

Masha Lankovsky’s edition and English translation of Yankelevich’s writings is forthcoming with Oxford University Press.

Masha Lankovsky previously published an article on Yankelevich, entitled 'Learning from the Inside Out' in The Strad's February 2011 issue. For more technical guidance, subscribe to The Strad or download our digital edition as part of a 30-day free trial. To purchase back issues click here.

No comments yet