Vahur Luhtsalu examines how the cello has aligned itself with royalty throughout history to the present day

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Rex instrumentorum – the king of instruments… The first known use of this metaphor is attributed to Mozart, who wrote to his father Leopold on 17 October 1777: ’In my eyes and ears, the organ is the king of all instruments’ (’die orgl ist doch in meinem augen und ohren der könig aller instrumenten’).

The organ has long been intertwined with the authority of religious institutions, governments, and sacred traditions. Mastery of the instrument demands exceptional musical skill, while its construction and maintenance call for both technical engineering proficiency and substantial financial investment—resources that often rely on collective backing from communities, private benefactors, or public institutions.

If the organ is the king of instruments, which instrument do kings themselves play?

The answer may surprise you: it is the CELLO.

From 16th-century royal courts to modern-day monarchs, the deep and captivating sound of the cello has long symbolised power and elegance. Surprisingly, the earliest surviving example of a modern violin-family instrument, crafted in 1538 by Cremonese luthier Andrea Amati (1505–1577), is not a violin at all, but the ’King’ cello. In 1560, it was painted and decorated as part of a set of 38 string instruments commissioned for the newly crowned ten-year-old King Charles IX of France (1550–1574) and his court. The set was ordered by the king’s mother, the Italian noblewoman Catherine de’ Medici, and the instruments were adorned with the royal coat of arms and the Latin motto ’Pietate et Iustitia’ (’Piety and Justice’) — a manifesto of Medici dynastic power.

Though it is unknown whether Charles IX, who wrote poetry and was more a patron of writers than a musician, ever played any of these instruments himself, the set was used by musicians of the French royal court for over 200 years—until the dramatic events of the French Revolution (1787–1799). Today, the ’King’ cello is preserved at the National Music Museum in South Dakota, US, standing as one of the oldest surviving members of the violin family.

With a devilish smirk and a hint of cellistic superiority toward violinists, perhaps we can now agree to refer not to the ’violin family’ but the ‘cello family’ of string instruments from here on. Shall we?

While violinists search for words worthy of a response to such unprecedented audacity, let us recall that throughout history, many crowned heads have cherished (cello) music and even practised the cello themselves. One such figure was Friedrich Wilhelm II (1744–1797), King of Prussia from 1786 until his death. As the nephew of his predecessor, the enlightened monarch, successful military leader, and devoted flutist-composer Frederick the Great (1712–1786), he strove in every way to follow in his famous uncle’s footsteps. His court orchestra, with 70 full-time musicians, was considered one of the largest in Europe. Moreover, Friedrich Wilhelm II was a passionate cellist: whenever state affairs permitted, he spent approximately two hours a day playing the instrument.

The intensity of his cello practice is vividly captured in a letter describing a lesson with the renowned Italian cello virtuoso Carlo Graziani (first half of the 18th century–1787): ’I played the cello with Graziani and exerted myself so vigorously that my hair ribbon loosened, my hair flew wildly around my head, and all the powder, makeup, and sweat melted on my face. Now I must redo my hair and change into a fresh shirt, for my body is drenched in sweat.’ —Letter to Wilhelmine Enke, circa 1780.

Later, Friedrich Wilhelm II refined his skills under the tutelage of the French cello virtuoso Jean-Pierre Duport (1741–1818). A significant portion of the king’s free time was devoted to music-making and interacting with musicians. It is no exaggeration to say that without the influence and patronage of the cellist-king Friedrich Wilhelm II, the golden age of classical chamber music—particularly the quartets and sonatas composed during this period—would have been markedly poorer. His dedication to music fueled the creativity of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. This is strikingly evident in:

- Haydn’s six string quartets op. 50 (1787),

- Mozart’s posthumously published ’Prussian’ Quartets K. 575, 589, 590 (1789–1790),

- Beethoven’s first two cello sonatas pp. 5 (1796), published after Friedrich Wilhelm II’s death.

All these works were dedicated to Friedrich Wilhelm II, and in each, the cello’s role is far more prominent than was customary in chamber music of the era.

King George IV of Great Britain and Hanover (1762–1830) was a skilled cellist who had occasional performances at court concerts and his ornately decorated cello ’Royal George’ Cello by William Forster 1782 remains preserved to this day. He likely received guidance from the court’s top cellists, such as James Cervetto (1748–1837) and John Crosdill (1751–1825), with whom he also collaborated musically. George IV’s passion for music extended beyond performance: he actively supported composers (including Joseph Haydn and Gioachino Rossini) and musical institutions. For example, in 1822, the Royal Academy of Music opened its doors under his patronage, now a globally renowned center for music education.

Not everyone approved of George IV’s cello pursuits. A satirical engraving from the 1820s, for instance, likened him to the infamous Roman emperor Nero, depicting the king atop the turrets of Brighton’s Royal Pavilion—a structure famously redesigned and expanded by British architect John Nash at George’s request between 1815 and 1822—playing the cello while the nation descended into chaos. Such scathing satire did not deter the king. Beyond invigorating Britain’s musical life, George IV’s regency (1811–1820) coincided with the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars in Europe at the Battle of Waterloo (1815), solidifying Britain’s position as Europe’s leading power—despite simmering domestic economic and social tensions.

Less widely known to the general public is that Emperor Emeritus Akihito of Japan (born 23 December 1933; reigned 1989–2019) has cultivated a bond with the cello for some time, first becoming acquainted with the instrument, reportedly after World War II. Akihito’s passion for music has been passed down to his eldest son, the current Emperor of Japan, Naruhito (born 23 February 1960; ascended the throne on 1 May 2019), who plays the viola, and to Naruhito’s daughter, Princess Aiko (born 1 December 2001), who has learnt to play the cello, following in Akihito’s footsteps.

Delving deeper into the history of cello-playing heirs to the throne, the British Royal Collection includes a notable 1733 oil painting by Philip Mercier (?1689–1760), titled The Music Party. It depicts Prince Frederick Louis of Wales (1707–1751)—eldest son of King George II (1683–1760) and direct heir to the British throne—playing the cello alongside his sisters, Princesses Anne, Caroline, and Amelia. For its time, this artwork is somewhat unconventional: members of the royal court, let alone heirs to the throne, were rarely portrayed playing musical instruments. Yet it offers insight into the rising popularity of cello performance in the 18th century, further evidenced by the fact that British luthiers produced numerous cellos during the 18th and 19th centuries, many of which remain highly prized to this day.

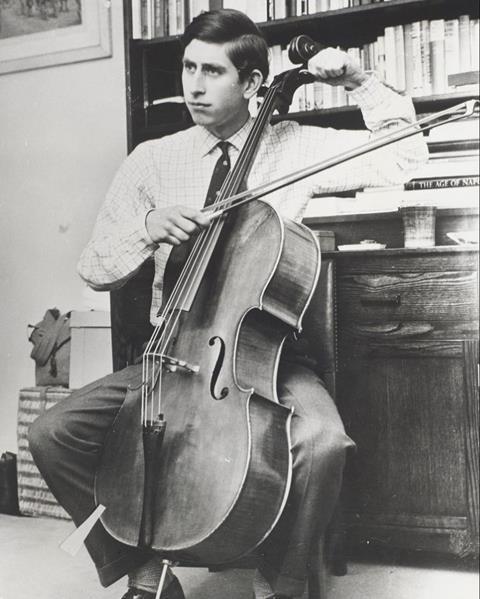

In the realm of modern monarchs and their musical pursuits, media attention has centered most notably on King Charles III (born 14 November 1948; ascended to the throne on 6 May 2023). A simple online image search reveals countless photographs of him holding a cello—though recent photographs of him actively performing are scarce. However, as demonstrated by Emperor Akihito of Japan, who was photographed playing the cello in 2005 at age 72 and reportedly continued practising in subsequent years, it is never too late to reawaken one’s instrumental skills. The modern era, moreover, offers a far wider array of cello instructors than was available during the reign of George IV—an advantage that could inspire even monarchs to revisit dormant passions.

Being a king has always demanded a vivid imagination, leadership acumen, unshakable resolve, and a delicate equilibrium between tradition and innovation to ensure a nation’s purposeful, sustainable development—aligned with the needs of its people.

Much like the organ reigns as the ’king of instruments,’ the cello has historically been not just a favourite plaything of the aristocracy but also a tool through which kings, princes, and princesses shaped their character, personal identities, and the cultural legacies of their royal houses and realms. And should anyone doubt this, Friedrich Wilhelm II or George IV might arch a brow and reply in a raspy voice: ’We play’d the violoncello. And what art dost thou practise?’

Vahur Luhtsalu is a cellist, music educator and publicist.

Read: Deconstructing the Andrea Amati ‘King’ cello

Read: King Charles III: Four times the new monarch showed his deep love for classical music

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

The Canada Council of the Arts’ Musical Instrument Bank is 40 years old in 2025. This year’s calendar celebrates some its treasures, including four instruments by Antonio Stradivari and priceless works by Montagnana, Gagliano, Pressenda and David Tecchler.

No comments yet