She was the niece of Mahler who rose above the terror of Birkenau to bring music to her fellow prisoners. To commemorate Holocaust Memorial Day, The Strad revisits Richard Newman's article on the violinist Alma Rosé, who died 70 years ago

Alma Rosé’s last journey began in the inhumanly packed cattle cars of a Nazi ‘Judentransport’, Convoy 57, from Paris’s Bobigny station at 9am on 18 July 1943. For the next nine months the niece of Gustav Mahler would make musical history as a prisoner in the shadows of four crematoria in the Nazi slave-labour-extermination camp of Auschwitz’s satellite, Birkenau.

Until her arrest almost eight months earlier in Dijon, an hour and a half from safety in Switzerland, she had managed to survive the Nazi era. She had even engineered ? with the help of Carl Flesch and Sir Adrian Boult ? the escape to safety in England of her famous father. She had been safe in England, too, with the Viennese lover who later abandoned her in June 1939.

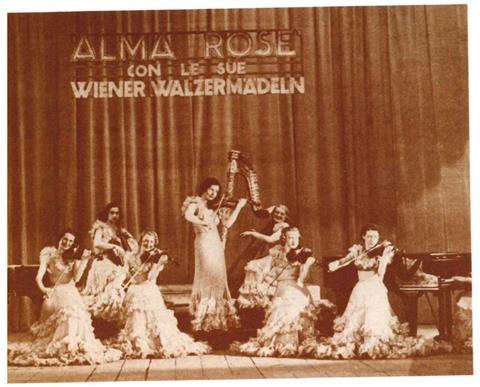

Rosé’s arrival at the camp’s railway siding was in bitter contrast to her previous engagements in nearby Krakow, Poland, just a 45-minute drive away. She had appeared there at least twice – as a violinist appearing with her former husband, the Czech violin virtuoso Váša Příhoda, and in 1935 as a conductor of her celebrated women’s orchestra, the elegant Wiener Walzermädeln which she founded and led throughout Europe.

Rosé was among a handful of women ‘selected’ for the Experimental Block. After processing – the shaving, shower, tattoo on the left arm with number 53081 and issue of prison garb, Rosé was directed with the other women to the brick block 10 in the main Auschwitz camp.

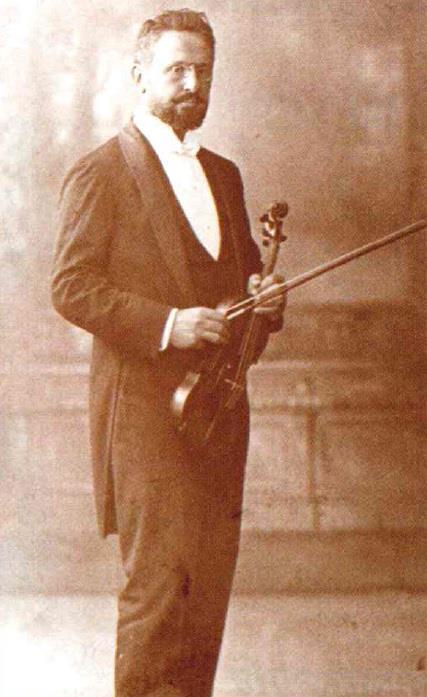

There was something about the dignity that Rosé assumed in contradiction to the surroundings that drew the attention of a young Dutch woman among the nurses in the block, Ima van Esso. She and Rosé suddenly remembered each other, for Rosé on piano had accompanied van Esso on flute back in Holland. That dignity came from a distinguished Viennese past among the leading composers and performers who had been part of her world. Her mother, Justine, was the sister of Gustav Mahler; her father Arnold Rosé, the concertmaster for more than half a century of the Vienna Philharmonic and the Vienna Opera, and leader of the famous Rosé Quartet. From her birth in 1906 she was surrounded by many of the most acclaimed musicians of the day.

The camp office in Birkenau, under whose direction Auschwitz’s block 10 was administered, was alerted to Rosé’s presence. She now turned to her most effective tools: her personality and her music. Her most urgent need was her weapon of choice – her violin. Believing she was going to her death she asked that final wish to be granted: a chance to play the violin again. She was apparently given a marvellous instrument - Nazi booty from an unfortunate arrival of unknown fate. It was the first violin she had touched since 12 December the previous year, when she had given her Guadagnini to a Dutch friend for safekeeping.

Rosé held the instrument tightly until the two SS guards left for the night, locking the doors from the outside. Inmates were posted to watch if anyone approached. As Rosé played the first notes, the locks of the doors seemed to melt. ‘Beauty was a long-forgotten dream in block 10 until that night. Nobody there could have dreamed of such beauty as her playing at the moment,’ said van Esso.

Word of Rosé’s playing prompted another prisoner, Magda Hellinger, to begin what became a grotesque cabaret, women parading in hospital linen and dancing – Rosé and Mila Potasinski teaching the tango and czardas respectively. Even Sylvia Friedman, the prisoner-nurse who worked with the experimenter Dr Carl Clauberg, would sometimes join in the dance which would occasionally conclude with a meaningful kiss’, said van Esso.

Over in Birkenau two prisoners, Zofia Czajkowska and Stefania Baruch, had set up a women’s orchestra a few months previously which now needed firmer direction. Their repertoire was mostly Polish folk tunes and simple marches, or popular songs that would please the guards. At one stage a delegation from the group went under guard to the main camp, Auschwitz, to negotiate for instruments and music with the professional musicians in the main camp’s orchestra. Slovakian–Jewish Helen Spitzer Tichauer was herself a gifted young mandolinist, and as a key member of the Birkenau office staff accompanied the delegation.

Yvette Assael described how SS Maria Mandel, the force behind the orchestra’s inception, had arranged a transfer to Birkenau for Rosé from block 10 on the strength of her talent. On her first day an SS officer merely introduced her as a new member for the orchestra. The next day the SS told the women who Rosé was, and that she was going to play something for them. ‘We knew she was really something. Then they announced that she was the new conductor.’ She had given a life-saving performance. When Rosé took command of the music block Czajkowska became the block senior (administrator).

Said flute player Sylvia Wagenberg: ‘She turned the orchestra upside down on its head... We played from morning to night.’

When Rosé organised her Wiener Walzermädeln, she had the best music conservatoires in the world from which to choose players; now almost none of the orchestra in front of her, trained or untrained, had had much music for two years or more and most had mental and physical scars from persecution and arrest.

‘No one ever made music under such conditions,’ said Tichauer, describing the resources – ‘bare rock’ – from which Rosé began. Music in the setting of a concentration in any case is the ultimate irony. Viennese doctor Ella Lingens Reiner, a frequent authoritative witness at war crimes hearings related to Auschwitz–Birkenau and Dachauk, said: ‘Hardly a day passed when one’s survival was not at stake.’ Outside of a few havens such as the music block, life expectancy in the camp was from a few weeks to a few months.

Fanny Kornblum Birkenwald recalled the terror she felt when Mandel came to the barracks one day and ordered Rosé to play Sarasate’s Zigeunerweisen.’ She said she came from hearing the piece on the radio and wanted to compare. We played like angels. Mandel responded to an anxious Rosé that the orchestra gave a better performance than she had heard on the radio. We gave a sign of relief.’

Rosé, too, would compare the performances of the orchestra, saying that a selection was played well enough to meet her father’s Viennese standards. When she agreed they had played well, they thought it the highest praise. The concertmistress, Belgian Jew Hélène Scheps, as recently as 1985 said she had never heard another ensemble bring the same beautiful quality to their music that Rosé developed in Birkenau. As for Rosé herself, Scheps has said that when she hears Itzhak Perlman play she is reminded of Rosé.

For the orchestra’s concerts the women wore blue pleated skirts, white blouses and lavender-coloured kerchief head coverings. It was a far cry from her Wiener Walzermädeln with gowns she and couturiers had designed, but she was adamant that the women wore them as though they were high style, meticulously clean and unwrinkled as much as possible.

The question inevitably arises of how the women felt when performing in the camp, as an ancillary to the hateful regime of the SS. That question also begs another, according to cellist Anita Wallfisch Lasker: ‘What was the alternative?’

The German Jew Hilde Gruenbaum Zimche, chief copyist and Rosé’s close friend, had high praise for Rosé when she described her as like a sabra, a thorny cactus-type plant with a refreshingly sweet fruit: ‘Rosé was hard and strong as a queen on the outside, but so different inside.’ She said Rosé was a completely assimilated Jew, but she deny her Jewishness.

To most of the women Rosé did not appear to be afraid of the SS. The French Jew Violette Jacquet Silberstein recalled that after leaving the camp hospital having suffered typhus, she was too weak to keep up with the orchestra as it paraded to the gate.

As she lagged behind, SS Franz Hössler stopped her and called to Rosé, demanding to know if the girl was too lazy or too ill to keep up. Being identified as such could have meant being sent to the gas chamber. Silberstein credited Rosé with saving her life at that moment: ‘Alma answered truthfully. I had had typhus and was still weak. But she also lied for me, saying: “This is one of my best violinists”. Hössler responded: “Very well. I will see that she gets extra rations for next three months for her rehabilitation.” I was by no means even a good violinist.’

During the winter of 1943–44, the rigorous schedule and constant tension were too much for the musicians. Fainting spells and collapse from exhaustion prompted Rosé to persuade the SS to allow the women to take an unheard-of short rest after lunch. ‘We would go to bed and sleep,’ Zoscha Cykowiak recalled.

The lukewarm morning showers and the stove for the music room were among other privileges denied other prisoners. The two daily roll calls, held outdoors for other blocks, were inside for the orchestra in winter. The bunk beds with blankets were a far cry from the crowded bunks of other blocks.

On the one hand, the SS was hungry for more and more music. With the help of Tichauer in the camp office and a staff of women to line paper for music, Rosé was able to have her arrangements written out by a staff of copyists in the music block.

It became obvious to the women, said Cykowiak, that Rosé was putting superhuman effort into her work. Allowed a light in her room at night she would often work the night through. They were all up before dawn, taking chairs to the gate and playing marches for the work parties marching under guard to jobs outside the camp. At day’s end the orchestra was again marched out to the gate, this time to play for the return of the exhausted, often beaten or injured work parties in time for the evening roll call.

In a BBC interview in 1996 Anita Lasker Wallfisch, with carefully chosen words, said she did not believe that Rosé was motivated by fear of the SS, that ‘if we don’t play well we’ll go to the gas... It was an escape somehow into – excellence.’

How could the orchestra play in the contradictions of their situation: music-mad SS officers crying over a piece of music after presiding over a ‘selection’ of weakened, diseased, dying prisoners or new arrivals for the gas chambers? Some among the inmates said the concerts that the orchestra gave — for which prisoners lined up hours before – actually made them more depressed by their situation than beforehand yet the majority said the music, with Rosé as soloist o playing as though she were in a crystal-chandeliered ballroom, reminded them that beyond the hanging at crematorium smoke might still be hope of life, of love and beauty.

Manca (Margita) Svalbovå – a Jewish medical student deported from Bratislava who became Rosé’s beloved ‘Dr. Mancy’ – believed that Rosé used music as a means of escape. Without it, said Svalbovå, she was like a bird with bloodied wings beating against the bars of its cage. Music enabled her to take flight and leave Birkenau behind, ‘covered as if by a night-cloth.

Playing beside Héléne Scheps was the Polish non-Jewish violinist Helena Dunicz Niwinska. She and her mother had been arrested on suspicion of hiding two members of the resistance. Her mother died in the camp of dysentery. When the Auschwitz museum told her of my research, sloe wrote to me, her first letter lamenting the fact that Rosé was not – at that time – listed separately in any musical lexicon. In her long and detailed correspondence since that time she related stories of efforts made by Rosé to be sure her women were well treated. The presence of Rosé, as a ‘Prominentin’ (a prominent person), merely making enquiries about a patient in the camp hospital assured one of a better bed and more attention.

When Fanny Kornblum Birkenwald contracted typhus, her friends felt great anguish. When she recovered and returned to the music block, Scheps Wrote: ‘She looked horrible – her face like a triangular mask with holes for her big brown eyes. She was so happy to be among us again. When Rosé heard that Fanny’s mother had died of typhus, she asked two of us to break the news to Fanny. We did it with great care; we are one: more than ever sisters!’

So inviting was the atmosphere in the music block that enthusiasts among the SS — including high ranking Dr Mengele, Mandel and Josef Kramer (later known as ‘the beast of Belsen’) — would visit to listen. Their passion for operatic ensembles often tested Rosé’s capacity for arrangements. Years later Eva Stojowska marvelled with a deep singing-actress voice how Rosé coached women to sing the male line in a score. Zoscha Cykowiak recalls that a young SS man who hoped to become a composer came to show Rosé a composition. Rosé played it and made some frank suggestions. One runner in the camp was stunned one day when she reported that Rosé was engaged in conversation with Mandel. ‘It was considered incredible that a prisoner might be allowed to sit with a jailer, but Mandel, a fellow Austrian, was devouring Rosé’s stories of her tours.’

According to one report of a concert in the bath-house, a number of SS women were joking and interrupting the performance in which Rosé was playing a solo. She stopped and angrily said: ‘Like that I cannot play.’ Silence followed; Rosé then played, and no one disciplined her.

Rosé died on the night of 4-5 April 1944, two days after a birthday party for a fellow prisoner functionary at Birkenau. The cause, it is believed, was botulism.

Musical groundbreakers: Ševčík’s female pupils

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

Currently reading

Currently readingAlma Rosé: the violinist who brought music to Auschwitz

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

1 Readers' comment