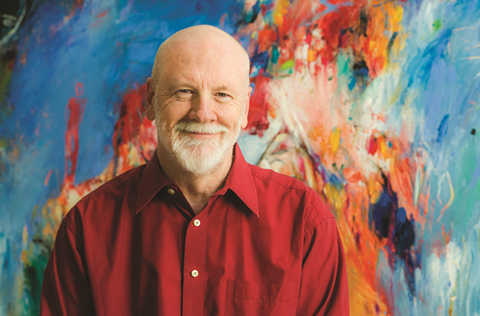

The Australian violist and composer on taking career risks and the unique insights that came from playing the viola in an world-class orchestra

I learnt the violin initially, but was taught by a violist in Brisbane called Elizabeth Morgan. She was my teacher for close to ten years and noticed at some stage that my character might be a good fit for the viola. She was absolutely on the money.

I felt more at home in the middle of a texture than on top of it. Later, while playing in the Berlin Philharmonic I had the feeling of being ‘in the engine room’, observing everything going on around me. Although I’d enjoyed pursuing my viola studies from a solo perspective, I felt most complete playing chamber music and then in the orchestra in Berlin – an experience that taught me so much about composing.

Germans like to use the English phrase ‘learning by doing’, and that’s exactly what was happening; I never studied composition, but in the midst of the orchestra I could hear what worked and why. Perhaps being a violist gives you the opportunity to do that in a way that being a violinist doesn’t; being less busy, with fewer notes to play, gives one more time to look and listen!

Lots of composers try not to listen to much music during a project, but I’m not like that at all. I tailor my listening to whatever it is I’m working on at the time and draw on what I can hear, just like a bowerbird assembling its colourful nest.

Recently, that has meant finding lots of cello concertos. It’s been fascinating to listen not only to the acoustics of recordings – where the cello is right under the main mike – but also to live performances where the sound behaves very differently. That’s something I’ve learnt from playing pieces like the Walton Viola Concerto and through refining the orchestration of my own Viola Concerto.

The assumption that audiences won’t enjoy hearing something new is a serious problem. I say that as both a performer and a composer. The marketing departments of big orchestras and other institutions hold too much sway and the bar is set too low as a result. Other art forms, like dance, theatre and visual art, are much more open to challenging their audiences.

Ultimately I was too curious. That overwhelming sense of security and certainty gave me the willies

I believe that people genuinely want to experience how new works can speak to the cornerstone repertoire they already know so well. Unless we expect and help foster a sense of curiosity in our audiences, we’ll risk boxing ourselves into a corner and consigning classical music to a museum.

I left the Berlin Philharmonic to concentrate on composing when I was in my late thirties. I’d been in the orchestra for nearly 15 years and I could see quite clearly what I’d be doing in another 30. Ultimately I was too curious. That overwhelming sense of security and certainty gave me the willies; I had to find out what would happen if I went down another route.

Overnight I chose to go from a well-paid, tenured position to being completely on my own. It was scary – I didn’t know if the phone was going to ring. Years earlier, however, I’d been given some excellent advice by the orchestra’s principal violist and my Berlin teacher, Wolfram Christ: to use my time in the orchestra to keep developing as an artist, not just to play as part of a section, making up the numbers. So I decided to find out how else things might unfold.

This article is from the August 2018 issue of The Strad

INTERVIEW BY TOM STEWART

Watch: Brett Dean plays his own viola concerto (extract)

1 Readers' comment