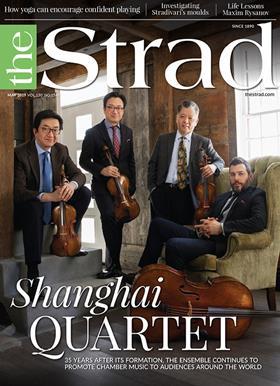

The players of the pioneering ensemble, which is celebrating its 35th anniversary, speak to Charlotte Smith about forming at a time when Western chamber music was barely understood in their native China

The following extract is taken from The Strad’s May 2019 issue, available to download here. To order the print edition, click here.

‘When we formed the Shanghai Quartet in 1983 chamber music in China was almost non-existent,’ says the ensemble’s first violinist Weigang Li. ‘Western music had been introduced to the country in the 1920s and 30s, and the first generation of classical musicians included my grandfather, a violinist, who played in a quartet with Yo-Yo Ma’s father (also a violinist) before the latter moved to Paris. But most Chinese musicians, even by the 1980s, simply weren’t aware of the scope and depth of this fantastic repertoire.’

Li is speaking to me at the 2018 Shanghai Isaac Stern International Violin Competition, where he is serving as a jury member. His fellow quartet members are here too, providing the professional element for the chamber music round. The significance of the Stern name is not lost on Li, who in 1979, at the age of 15, was featured in the Oscar-winning documentary From Mao to Mozart: Isaac Stern in China.

Meeting and playing for Stern was a momentous event for the violinist, who at the time was a student at the Shanghai Conservatory Middle School. Just two years later he was selected for a year-long cultural exchange programme with the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, an eye-opening trip which introduced him to Robert Mann (later a teacher), Nathan Milstein, Henryk Szeryng and Efrem Zimbalist.

Thus, when the Chinese Cultural Ministry announced a chamber music competition for students of the major Chinese conservatoires in 1983 – the prize being the chance to compete in the 1985 Portsmouth International String Quartet Competition (now the Wigmore Hall International String Quartet Competition) in the UK – Li was unable to ignore the opportunity.

‘I was a third-year student at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music and my brother Honggang Li was also a violin student,’ he explains. ‘We found a decent violist and cellist with the intention of working hard for a year in the lead-up to the first contest. We had no serious ambitions to form a professional group. All we wanted was the chance to visit England – where none of us had ever been – for three weeks!

‘We had no idea how to prepare, so we grabbed every teacher who came through the conservatory. It became more and more serious to the point that we would rehearse for five to seven hours every day. We worked especially on intonation because we realised this was particularly hard to get right, eventually tuning note by note. Looking back, that sounds crazy, but we didn’t have any fundamental principles from which to work. All we had was our intuition and relatively good ears.’

The strategy worked: the ensemble won not only the Chinese competition but also second prize at the Portsmouth contest. ‘We weren’t at all upset with second prize – it was a God-given gift. Winning first prize would have meant an instant schedule of 55 concerts over the next year and we simply weren’t ready to become professionals.

‘But winning second stood us in good stead going back to China. All of a sudden we were in the newspapers and magazines because the Chinese had never won any prizes in chamber music before.’

Read the full exclusive interview in The Strad’s May 2019 issue, available to download here. To order the print edition, click here.

No comments yet