The BAFTA Award-winning composer of scores including The Da Vinci Code and The Little Prince talks about the fundamental role of the string sound in film

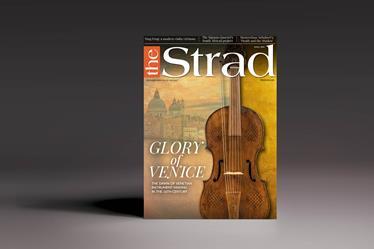

The Strad's February 2016 issue features an article on the importance of strings in film music - download now through The Strad App or on desktop computer.

On strings’ ability to signal emotion in film

I am working on a movie at the moment where it has been decided that strings won’t be used. Now this really requires a lot of lateral thinking and the taking of big strides outside the composer’s normal comfort zone. I’ll tell you why, as I understand it.

The bow on string – be it violin, viola, cello or double bass, or, in other cultures, the erhu, sarangi and so many others – makes a true and natural connection to the human nervous system and emotions. That sounds odd. But the touch of a bow as it excites the string – nothing else does that or has that effect. Strings can swell and die as humans breathe, and can tremble or sigh or startle as we do. It’s all very physical, as well as emotional.

The fact is that for every one string instrument we effectively get at least ten. Let’s add them up. There’s arco normale, pizzicato, tremolando, sul ponticello, sul tasto, con sordino, flautando, and all of those with or without vibrato (even pizz!). What other instruments of the orchestra can enrich your sonic palate to that degree? We know that nothing else comes close.

Orchestral strings have been used to underscore films ever since there was sound available in the cinema. It’s in our audience DNA the world over, from Chinese blockbusters via Bollywood to all that we’ve done in Eastern and Western Europe and the Americas. Strings with everything. It just works.

On the scoring process

There are many different ways to approach scoring a movie. There used to be a time when only a tiny handful of people on the planet regularly saw films that had no music in them – film composers, editors and directors and very few others. I remember those days with mixed feelings. Watching a great movie without a score was like a glorious invitation. Watching a terrible movie with no music on it was another matter altogether.

These days, though, almost every time you see a film in its post-production phase, it already has what they call a 'temp score' on it, made up of suitable music taken from other movies with the idea of helping to get everyone in the appropriate mood. This sometimes works for you, sometimes against. In the industry, many composers would consider it an evil, but nearly all would agree it’s a necessary one.

If I were feeling naughty, I could certainly say that some composers would not know where to start without a temp score in place. But films are so different – and so are directors and target audiences – that you end up reinventing the wheel every time. Or, at least, trying to. Collaborations are totally unpredictable, but when they involve someone like Hans Zimmer (Harvey’s collaborator on several films), with his vast experience, you do tend to listen to what he has to say.

On a changing industry

There was a golden pre-technology age of film music, when the composer really needed to hear the whole score in his head as a through-composed piece and then conduct it to picture. These (mainly) men needed technical, as well as creative, genius. There were no demos for them, no computers, no click tracks. If I didn’t love all these scores, I at least found something to admire or to learn from in all of them.

Then came the Dark Ages (the 1990s and early 2000s), when scoring seemed to be thrown open to anyone with a home computer and movie company accountants salivated at the thought of how much money they could save. The results were predictable – terrible sampled sounds, awful schoolboy harmonies and cheap, pounding drums.

Through all this, though, the golden generation continued, operating on a wholly different level, and eventually we emerged into a new golden age. The democratisation of film scoring had brought on new talents that would have lain unnoticed in earlier days, and some of these new voices really started to learn how to do it and get it right. The sheer quality of the sound, in cinemas and at home, improved beyond recognition and, frankly, it all became very different. Harmony and melody – the two elements that could fight their way through the terrible sound systems of the pre-digital age – became less important and sonic craftsmanship became a very big deal. I still like, love and learn from a lot of modern film scores, even though some of the composers have got there via a very different path.

On discussions with directors and financial limitations

Discussions with directors are such fun. They ask you for strings, you tell them how much the producer has allocated to the music budget and a really interesting conversation develops from there. But seriously, music budgets for all but the most glamorous movies are being squeezed dry by accountants who know that composers are a soft target. The way it works now is that composers are offered a 'package', meaning effectively, 'Here’s some money. Come back with a score.'

Suppose the package is £15,000. If the composer really wants strings on his score, it often means that he is in danger of having to do the job (every laborious element of it) for free, just to have his or her music sounding as it should. In practice, though, if the budget can only support a small number of musicians, the composer will nearly always book just strings – and 'fake up' everything else, including, quite possibly, the mortgage payments. And that, my dear friends (who’ve worked so hard to coax such beautiful and varied sounds from such fiendishly difficult instruments), is the clearest tribute of all to the universal and eternal power of horsehair pulled across a string.

The Strad's February 2016 issue explores the special importance of the string sound in film music - download now through The Strad App or on desktop computer.

Watch: Alan Rickman plays the cello in Truly, Madly, Deeply

Photo: Richard Harvey conducts the film soundtrack for The Little Prince

No comments yet