Both great musicians taught Maisky that the cello is merely a means to an end

I started cello when I quit smoking. I was eight years old and announced that I wanted to play cello. But the latest age for starting in Russia was seven so I had two months in the summer to learn enough to apply for the music school in Riga.

My professor, Mikhail Ishkhanov was a wonderful teacher, but I don't remember that much about what he taught me. I think I was just gifted enough to get to the standard required.

Unfortunately Ishkhanov was very ill and he had to leave the school soon after I arrived. For several years I didn't have a good teacher, which was very damaging. But the standard in Riga was not that high, so I was considered one of the best even though I didn't do much work.

Ishkhanov returned to the school when I was 13 and told me to start studying seriously and move to the Leningrad Conservatory, where the standard was much higher.

I had a very good teacher there, Emmanuel Fishman but he was incredibly overworked, so I hardly ever saw him and I was left more or less to myself. Normally, Soviet musicians were put rigorously through the basics and had a very strong technical foundation.

Unfortunately I don't think I got this. I always call myself a half-amateur cellist, because I love music more than anything, but I don't really know much about cello playing.

In Leningrad I wasn't really given a method to follow. I wasn't prescribed lots of scales and exercises, but I did learn a lot of serious repertoire.

When I was 17 I took part in a series of competitions, culminating in the Tchaikovsky Competition in 1966, in which I won a prize. After that Rostropovich invited me to study with him at the Moscow Conservatory.

Rostropovich's teaching was full of intensity and unbelievable energy. He was incredibly demanding as a teacher because he judged everybody by his own high standards. It was very difficult, but always inspiring.

He hardly ever touched the cello and didn't talk about playing much either. He was much more interested in helping students to understand what a composer wanted to say. He was very busy, of course, so there were long periods when I didn't see him, but still we developed a very close relationship. I started learning with him just after my father died and he was very supportive. He replaced my father in many ways.

I studied with Rostropovich for four years. Then I fell foul of the Soviet authorities and spent 18 months in prison shovelling concrete to help build Communism. When I came out, I arranged to spend two months in a mental hospital to get out of military service. During all that time I didn't even see my cello. Eventually I managed to leave the Soviet Union and go to Israel. Rostropovich suggested I go to study with Piatigorsky, who was living in California.

Encountering Piatigorsky on a personal level was as important as studying with him. He was probably the most remarkable gentleman, in the highest meaning of the word, that I have ever met. He was already very ill with lung cancer and this was his last chance to share his incredible life experience. I only studied with him for four months, but I was with him almost every day.

His approach was very similar to Rostropovich: he never talked about cello playing. He stressed that in any piece of music you have a clear idea of your final goal and then find your own way to achieve it, because there are many different ways. How you reach it isn't really that important.

I always say that this was the best time of my life. That doesn't mean Piatigorsky was better than Rostropovich: that would be as ridiculous as saying Mozart was a better composer than Bach. But I think I was a better student with Piatigorsky, because I was more mature.

I am the luckiest cellist in the world - the only one to have studied with both these great cellists. If I am asked to pinpoint one thing which I learnt from both, it is that one should always remember the instrument is just a vehicle. It is there to help us achieve the ultimate goal, which is the music.

This article was originally published in The Strad's July 2003 issue.

Watch: 2Cellos, Mischa Maisky and Giovanni Sollima perform AC/DC’s Thunderstruck

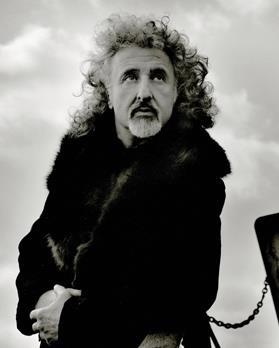

Photo: Mat Hennek/DG

No comments yet