Suggestions that instrumental care is too delicate a task for museums are dangerously wide of the mark, and pay scant regard to their educational objectives, argues Alex Robinson in this blog from 2014

Among the basic purposes of any museum are the preservation of historic artefacts and the education of visitors. Applied to musical instruments, these goals can seem at odds. On one hand, most instruments, no matter how finely crafted, were created and achieved renown as tools of the musician’s trade, designed above all to be played. Housing them behind glass, seen and not heard, deprives the visitor of the chance to appreciate this crucial quality. On the other hand, the physical forces exerted in performance are destructive by nature and risk serious and potentially irreversible damage.

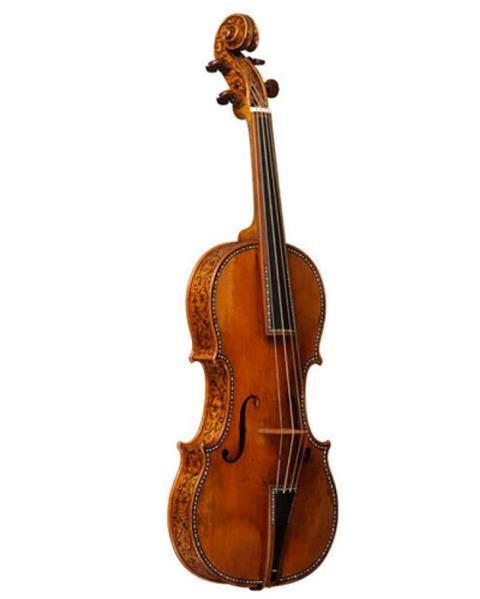

I had cause to consider this dilemma recently while viewing the impressive collection of instruments at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, which include the famous Stradivarius ‘Cipriani Potter’ (pictured) and ‘Messiah’ violins, and at least one Amati. From my conversations with curators it becomes clear that there is no single, unifying definition of how instruments should be preserved and displayed. However, the suggestion that valuable instruments are not to be exposed to the general public in any form, played or unplayed, is anathema to them.

I spoke to Colin Harrison, the Ashmolean’s senior curator of European art, and to him, allowing their collection of historic instruments to be played is unthinkable, the potential for harm simply being too great. Nonetheless, value exists in their display as works of primarily visual art. Despite the fact that the instruments can no longer be heard, their elegance can still be appreciated. Considering the intricate decoration of the ‘Cipriani Potter’, it seems to me altogether better that such a fine violin should be on display, even if silenced, rather than locked away for specialists’ eyes only. Surely a carefully-organised display can serve as the starting point for the layperson to begin to appreciate the craftsmanship and history involved, and to carry out their own further reading if they are interested in learning more.

This is a sentiment echoed by Andrew Lamb, curator of the same city’s Bate Collection of instruments. ‘We are not the gatekeepers of all human knowledge,’ argues Lamb; a curator’s mission is instead to find a means of introducing visitors to his or her collections so that they can find their own way of appreciating the exhibits. Although the Bate features many static displays, a number of (primarily brass and woodwind) instruments remain in playable condition and are occasionally used for recitals. ‘How do you explain in words the particular qualities of a given instrument’s sound? We simply lack the vocabulary to convey that,’ says Lamb. Performance, therefore, offers a unique educational opportunity, for example for scholars interested in the influence of particular facets of construction on the sound of an instrument. Of course, if an instrument is to be played, the risks of damage must be considered carefully before giving permission, particularly in the case of specimens having specific cultural significance or which are otherwise rare.

Few museums have facilities in-house for specialised care and restoration of instruments, but where specialist attention is required, external experts can naturally be called in. Of course, if instruments are maintained in unplayed condition, this will be required comparatively rarely – Harrison, for instance, points out that few of the instruments in the Ashmolean collection have ever required major attention. For smaller tasks, the Bate offers an intriguing possibility which combines the educational and conservational duties of a museum: volunteer members of the public, given proper training, regularly assist with cleaning and making minor repairs.

Although these are merely two examples, it is clear that a diversity of approaches exists among museums, with no one approach necessarily more valid than any other. As a result it should be possible for each type of visitor, whether a member of the public making their first foray into music or a devoted scholar seeking specialist information, to find a museum with an approach suited to their interests.

Perhaps modern technology offers a compromise which mitigates any damage while also allowing the instrument to be heard. Audio guides featuring recordings of instruments in a collection allow visitors to hear a brief impression of their sound, without the need for the instruments to be played frequently. Of course, a recording is no substitute for the freedom of a live performance, but where an instrument is truly too rare, too fragile, or too significant to be handled on a regular basis, then this still allows the appreciation both of its visual and musical qualities.

No comments yet