In addition to technical mastery, musicians need to understand the ‘game rules’ of every performing tradition and musical culture, write Dudok Quartet Amsterdam musicians Judith van Driel and David Faber

Children experience the world in a playful way. When we were young, making music used to be a fascinating game. The more we played, the more the game of music revealed endless possibilities for exploration and experimentation. However, as we grew up, the play element slowly but surely faded away.

As a string quartet, the Dudok Quartet Amsterdam is part of a particular performance tradition. During our studies we tried hard to absorb into our playing the wisdom passed on by our teachers, without realising that this kind of mimicry was almost imperceptibly replacing our own playful approach to the game.

During the 19th century, the historical canon of art (in all its forms) began to take shape. As a consequence, an ideal of ‘truth’ arose when it came to the performance of classical music. Composers of Brahms’s generation wrote music that was meant for eternity, which was performed by devoted disciples. The 20th century and the age of recording technology added another layer: that of the ‘absolute performance’. As a result, the highest aim for performing artists boiled down to imitating earlier performances as accurately as possible, both on record and live.

Over the past few years we have been deliberating about the way that our quartet performs ‘early’ music. How are we to discover something new in music that has been performed so many times and at such a high level? We found a very convincing answer in the work of Hans-Georg Gadamer, a German philosopher who shed light on hermeneutics, or the art of interpretation. He argued that people are embedded in a particular history and culture that has shaped them. The prejudices shaped by our tradition don’t hinder us in making interpretations, but are an integral part of it.

Gadamer’s ideas are reflected in our work as a string quartet. A musical composition gains significance with every performance. It is the task of a performer to translate the text (in other words, the music) handed down to us by, for instance, Brahms. That text has admittedly been more or less fixed, in the sense that the pitch and duration of notes are indicated, as are a few subsidiary instructions, but its actual meaning comes to light only when it is interpreted by a performer. A new rendition is thus not merely a reproduction or imitation. Every interpretation gives the work a renewed sense of understanding and perspective. There are no absolute truths in music; instead, every performance has its own immediate truth.

Last year we decided to record all of Brahms’s quartets. Questioning our preconceptions inspired us to immerse ourselves in the composer’s musical language and ‘game rules’. We delved into books about the development of performance practice surrounding Brahms and his contemporaries. Throughout our adventure, we fell in love with the sonority of unwound gut strings and experimented with the use of flexible tempo, portamentos and non-vibrato as means of expression. By replaying Brahms’s string quartets many times over a substantial period, we strengthened our conviction of how we wanted to express their meaning.

But playing among ourselves, in our rehearsal or recording studio, is definitely different from performing for a live audience! In a live concert, everyone in the room is participating in the same game. Musicians and listeners together step out of their ordinary life in order to immerse themselves in a collectively defined musical domain. And within this magic circle, the audience has a vital role: each listener brings their own preconceptions into play. Thus, the audience gives the music its own unique and immediate meaning, revitalising it at each performance. We encourage our audiences and fellow musicians to approach every concert as a game. By ‘playing along’, you no longer have to listen in a comparative or judgemental way. Instead, you can fully lose yourself in music, just as a child can be absorbed by their own play.

-

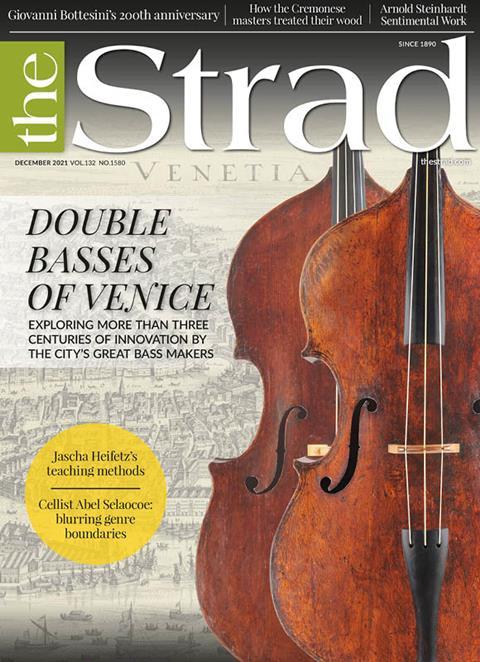

This article was published in the December 2021 ‘Double Basses of Venice’ issue

The north Italian city-state produced some of the country’s finest instruments . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- The Venetian double bass

- Celebrating Bottesini’s 200th anniversary

- South African cellist, composer and vocalist Abel Selaocoe

- Wood treatment on Cremonese instruments

- Heifetz as a teacher

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet