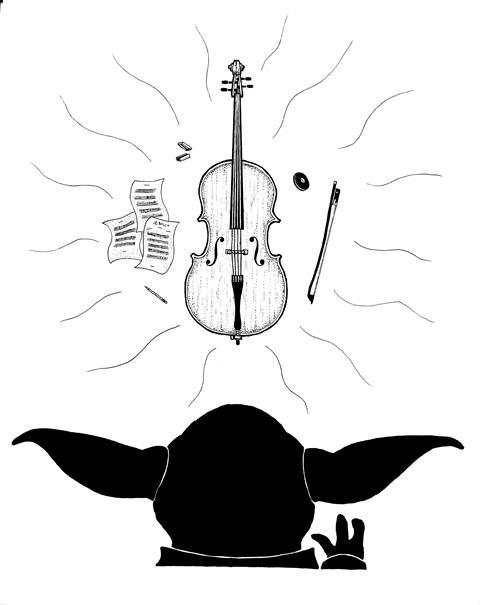

In the Star Wars universe, Jedi Master Yoda is the ultimate teacher – and his insights can be applied just as readily to string playing as to learning the ways of the Force, writes cellist Brian Hodges

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

This article appeared in the April 2020 issue of The Strad

Yoda is one of the most beloved characters in the Star Wars saga. The majority of the time we see him in the films, he is in a teaching role – the wise Jedi Master, doling out sage-like wisdom. As a lifelong Star Wars fan and a pedagogue myself, I have appreciated his insight and instructional approach, finding it highly relevant to my own teaching. Many times I have found myself working with a student and making a statement that is strongly reminiscent of something that Yoda says, because it matches beautifully with what I’m trying to get across. The following are three of his best-known quotes with ideas on how they can be applied to the learning process for string players.

‘Try not. Do, or do not. There is no try’

Sometimes, a student just needs to do whatever it is that we’re trying to get them to do without much thought. Of course, I’m not suggesting that students shouldn’t think. Quite the contrary. But often the student will get too tangled up inside their own head, inflating the issue. By simply doing the task – say, moving the left arm sooner to prepare for a shift – without overanalysing it, they often find that magic happens.

There’s also an important distinction to make regarding this concept of ‘trying’. When a student ‘tries’, it is often accompanied by a gritting of the teeth, tightening of the shoulders and a firmer grip on the bow. ‘Trying’ usually equals too much tension. Sometimes, the ‘don’t think – just do it’ approach can work miracles.

Illustration by Mason Allen

‘Train yourself to let go’

A very important aspect of performance is the act of letting go. A student who consciously lets their thoughts, actions, movements and breathing all flow from a centred place can experience a performance that has the sense of calm and control they desire. In most cases, however, this is easier said than done.

Students are used to overanalysing what they do, setting their jaw and forcing more sound out of their instrument. What they might not realise is that letting go can be applied to both physical and psychological aspects of their playing. By relaxing mind and body, and removing excess tension, shifts happen more easily, the vibrato loosens and the tone will improve. By trusting and relying on the level of preparation they’ve undertaken in the lead-up to the performance, students can let go of what might have kept them stuck in the practice or critical mindset of ‘trying’ instead of ‘doing’. Letting go of the type of analytical thinking that occurs in practice enables the student to enter the performance mindset, which consists of acceptance and confidence.

Luke: ’I don’t believe it!’

Yoda: ’That is why you fail’

Self-defeat is one of our biggest enemies. When students walk out on stage, about to perform a piece, and their mind floods with negative thoughts (’I’m not good enough’; ’Now, they’ll all know what a fraud I am’; ’I’m not ready’; ’I don’t deserve to be on the stage’), this can have disastrous effects on their performance and self-esteem. Tearing themselves down is the first step in assuring a performance won’t go the way they’d like. To counteract this, the best antidote is to perform—perform a lot —in order to increase the opportunity for more successful performances.

Performing is just like anything, it takes practice to succeed at it. Even performing for one or two people counts. Students need to perform often, preferably the same piece or group of pieces, for different people in different scenarios. It is important to simulate the nervousness they often feel in performance, so that they can learn how to deal with it effectively. They should play for friends, family members, other musicians. They need to put their pieces through the ringer, so that by the time the actual performance comes, they will have performed it numerous times. Each time they perform it, they should practise saying positive things.

If their mind starts to intrude with a negative comment, interrupt it with a positive one. Take stock of all the things that go well in a performance, rather than always focusing on the negative. Students need to remember that they are not a slave to their self-talk. Although it will take serious attention and work, students can change what and how they think about themselves and their performances to both feel and play better.

Self-defeat also has a way of showing up in the performance too, through body language, posture, and even one’s sound. An audience member wants to hear the performer in command of the music and presenting something beautiful, moving, or interesting. They don’t often, if ever, attend a performance hoping to hear self-defeat and doubt. And if something goes wrong, which is inevitable, students often let it bring them down, their sound gets smaller, their head and shoulders hunch down. I tell my students to keep focusing on the music, the expression, the message of the music, no matter what. It’s incredible what even the smallest amount of self-belief and confidence can accomplish in performance. Acting ’as if’ is a very effective strategy to build confidence and trust. When they practise acting (performing) ’as if’ they are confident, full of self-belief, or larger than life, pretty soon it won’t be an act at all—they’ll begin to believe it.

‘The greatest teacher failure is’

Failure is going to happen; it’s inevitable. Of course, there are varying levels of failure, from a slight memory slip of a few notes to having a complete blank-out during a piece. Every single musician has made a mistake or failed at some point, if not many, many points.

Truly successful musicians are the ones who have made mistakes, failed and learnt from them. I recommend that my students keep a journal and make notes after a performance. They should detail what went well and what needed improvement. They need to be honest and look for constructive comments, rather than crushing their ego with negativity. I encourage them to write down how they plan to address the items listed, and to map out practice tips to improve these elements for the next performance. It is virtually impossible to avoid mistakes, but a student can use that to their advantage and learn from them. If they are able to move on and move forwards, this can strengthen their resolve for the next performance.

’Pass on what you have learnt’

Even though I had excellent teachers in high school and college, in some ways I didn’t have a chance to really understand my technique and what I was doing at the instrument until I became a teacher myself. I didn’t take on students until my graduate studies, thinking I didn’t possess enough knowledge to teach younger students yet. Once I did start to teach, I found that I really had to put the spotlight back on myself in order to break down exactly what I was doing at the instrument, and thus, what I expected my students to do. How do I use my wrist at bow changes? How involved is my left arm in shifting? What are the fingers actually doing in my bow hold? How firm is my left thumb pressing on the back of the neck?

Now, I often encourage even my high school students to take on students. There’s the familiar adage that in order to really understand something, you need to teach it. I’ve found that once students start teaching, it initiates the process of really analysing their own technique and musicality in ways they hadn’t before.

Another aspect of learning through teaching is in their own practice. A technique that I highly encourage my students to do is recording (either audio or video) themselves in their practice sessions, watching it, and then documenting their observations. Attempting to hear their own playing in an objective manner (no matter how difficult this might be) and having to assess what is going on is an excellent way to improve their abilities at the instrument. It’s one thing for me to point out areas and specific items of improvement, but it’s another thing to pick it out on their own.

As teachers, we take inspiration from all kinds of sources, be they mentors, books, recordings or articles, and some of the best ideas stem from unlikely sources, yielding unexpected and positive results. The enlightened guidance of Yoda, for one, has made a great impact on my teaching and my students’ learning. As teachers, and lifelong students, may we find our wisdom wherever we can.

Read: Opinion: Jedi Wisdom for string playing

Read: John Williams at 90: Anne-Sophie Mutter’s ‘respect for this gigantic musician’

-

This article was published in the April 2020 Anne-Sophie Mutter issue

The German violinist discusses dedicating herself to Beethoven in 2020 - and why John Williams is one of the greatest composers of our time. Explore all the articles in this issue.

More from this issue…

- Anne-Sophie Mutter on Beethoven and John Williams

- Lutherie in 18th-century eastern Germany

- The Academy of St Martin in the Fields at 60

- The instruments of Pöpel and Kurzendörffer

- The great Hungarian string teacher Béla Katona

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet