Cellist and language therapist Dr Elizabeth Morrow describes developmental dysmusia - an inability to read a musical score - and offers guidance for teachers in overcoming the difficulty

About five years ago my professional life took a hard right turn, which has opened up a surprising area of inquiry. As a newly Certified Academic Language Therapist, I found myself in conversation with string teachers on a regular basis who were questioning how to help children who had difficulty learning to read music. It seemed to be a problem particularly in classroom programmes. When presented with such a student myself, I recognised behaviours familiar from Language Therapy – inconsistency, hesitation, lack of retention – that didn’t seem to improve when I applied my standard teaching practices. It appeared that his confusion stemmed from a fundamental lack of understanding about the entire system of note reading. Because there is no universal music-reading mandate, there is scant scientific research into this problem. Accordingly, I began investigating evidence of developmental dysmusia, an inability to read a musical score.¹

In conversation with friends and colleagues over several years, I found this issue to be more common than I had imagined. To expand my understanding, I issued an informal survey to string teachers and directors. Out of 84 respondents, 96.5 per cent said they had experienced students in their programmes or studios who did not or could not learn to read music within the context of standard instruction. 71 per cent said that it was common or somewhat common for these children to already have diagnosed learning differences, and almost 50 per cent affirmed that these children dropped out of their programmes.² This suggests a problem in need of a solution.

How can we help these students? The science of dyslexia research can help to inform the problem, and also inspire a solution. Because of our universal mandate for reading, dyslexia has been highly researched and remediation solutions have been developed through an approach known as Multisensory Structured Language Education (MSLE). As a Language Therapist, I use this approach daily to successfully remediate children who teachers and parents thought were incapable of learning.

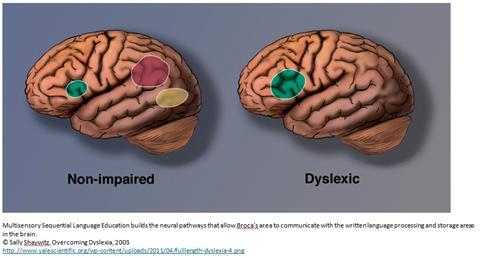

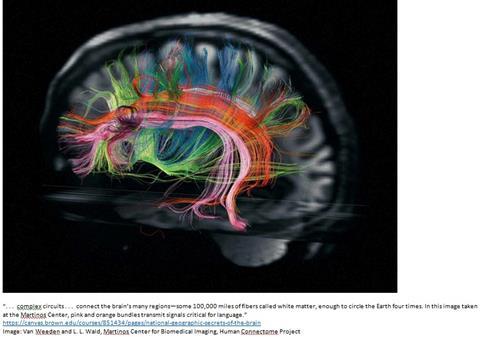

Dyslexia research shows us that there are several parts of the brain that need to communicate with each other in order to be able to read fluently. While dyslexic and non-dyslexic brains have the same basic structure, research has shown that dyslexic brains lack essential wiring that allows certain areas of the brain to intercommunicate, to process understanding, and to store learned information. MSLE can actually build the wiring necessary for the brain to read fluently.

What are the problems inherent in our string music education approach that cause students with learning differences to struggle? Could the MSLE approach be a solution? Most string education programmes are taught from the perspective of learning to play the instrument, not how to read music. However, this can confound brains that are not sufficiently wired for reading acquisition.

A few examples of these problems:

- String students are taught beginning with open strings. From a reading standpoint, there is an immediate disconnect between the first two notes learned, D and A. There is no obvious relationship between these two notes that allows the brain to retain the information. From the very beginning, students must make random associations that don’t support retention in new learning.

- Duration instruction begins with quarter notes (crotchets). For the purpose of beginning playing instruction, it is a logical choice, but from a reading standpoint, it is like learning the alphabet beginning with the letter M. The brain has to process additional learning in two different directions, toward longer and shorter durations, compounding learning challenges.

- For logical reasons, combined classroom programmes typically begin in the key of D major. However, from a reading standpoint this approach doesn’t encourage students to draw upon alphabetic connections. Also, they are learning chromatic alterations without understanding meaning (one of my challenged students told me that a sharp means more fingers!) Acquiring knowledge without understanding the underlying logic makes it very difficult for certain brains to correctly build wiring.

A learning system based on MSLE uses all available sensory pathways to enhance memory and learning and contains these principles³:

- Instruction must be systematic and cumulative.

- It follows the natural order of musical language, beginning with the easiest and progressing methodically to subsequent elements, never skipping steps.

- Every element is presented explicitly and directly, and inference is never assumed.

- Each instructional session is diagnostic – the instructor must assess what is appropriate for the next lesson.

- Synthetic and analytical instruction must be integrated into all teaching.

Some examples of applying these principles to music reading would be:

- Using discovery learning to build understanding, beginning with the staff (stave), its history, structure, and meaning.

- Learning notes (one at a time) by following the alphabetic principle – beginning with A!

- Teaching accidentals only after students can name and identify at least one octave and have been fully introduced to the concept of half steps and whole steps.

- Beginning duration instruction with the whole note (semibreve), which has the added feature of being different from every other duration, as it has no stem. The whole note cannot be confused with another duration, and the learning of additional durations proceeds in one direction only.

- Practising handwriting notation, as dyslexia research shows 'the effort of manually holding a writing instrument and forming letters engaged the brain’s neural pathways.'4

- Adding new learning incrementally, and only when previous learning is secure.

- Learning simultaneously to read notation and to write notation through dictation. Learning to analyse and to synthesise rhythms (break down and build up from component parts).

My work with struggling string students has demonstrated that this approach aids learning. It is not a quick fix, and it necessarily does NOT align with traditional classroom instruction. What it does do is draw on researched and proven reading systems to create a strong foundation of understanding (not just knowledge) upon which future learning can flourish.

¹Gordon, N. (2000). Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 42.

²Anonymous survey sourced from https://www.facebook.com/groups/positiveorchestradirectors/ https://www.facebook.com/groups/todaweb/ (Texas Orchestra Directors)

American String Teachers Association Conference attendees

³http://everyonereading.org/about/about-multisensory-structured-language-education/

4https://www.laurelschoolprinceton.org/new-handwriting-research/

Dr Elizabeth Morrow retired from the position of professor of cello at the University of Texas, Arlington in 2012 after 21 years of teaching. As a recitalist, she has concertised extensively in Europe and North America. As a dedicated pedagogue, she has been an active presenter at the American String Teachers Association conventions, a contributor to the ASTA journal (AST) and was founder and director of the Texas Cello Academy, an annual summer course and festival held at the University of Texas at Arlington from 2000-2011. While Professor of Cello at UT Arlington, she was inducted into the Academy of Distinguished Teachers, and in summer 2009, was awarded the UT System’s Regents’ Outstanding Teaching Award. In 2014, Dr. Morrow created the web site celloessentials.com, a free resource containing video instruction for pain-free performance on the cello. Dr. Morrow currently maintains a private cello studio in Arlington, TX, performs in the Dallas/Fort Worth area, and has expanded her teaching interests to include working with dyslexic children. She is a Certified Academic Language Therapist, and is currently researching teaching music reading to students with dyslexia and learning differences.

If you would like to contact Dr Elizabeth Morrow about your experiences or concerns regarding dysmusia please email: emorrow@uta.edu

No comments yet