Dr Tomas Cotik gives an introduction to the method and demonstrates techniques and exercises

This article covers a wide array of techniques and simple ways in which performers of all levels can achieve a more natural approach to instrumental playing by improving ease and freedom of movement. Practising these exercises will refine and heighten kinesthetic sensitivity offering the performer a control which is fluid and lively, enhancing performance and helping avoid unnecessary tension, pain, and potential injuries.

Identifying the subconscious habits that interfere with the operation of our innate coordination is the first step and more than half of the work in cracking them. A usual interference is the 'startle reflex', a movement-stopping reaction that kicks in when we are suddenly frightened. This is a very useful resource when we are about to step on a cliff, but counterproductive when we introduce it into our playing due to fears of a difficult shift, an audition, or an important concert. Other people tighten to set their bodies before they move with the unconscious assumption that this will improve their accuracy.

To help correct this, the teacher can ask the student to stop in the middle of the piece, leaving the bow on the instrument. The next step is to tell the student to unlock the knees, release the neck, release the jaw, allow the arms to flow out of the back, release the twist to the left in the torso, and then continue to play.

It is more important to practise taking care of the body than to focus solely on getting the passage right. Trying hard and wanting too much can lead to bad habits which are subconsciously associated with the goals. Patience is essential; as is not getting emotional about mistakes.

When we watch very good players, we can observe different bow grips, positions, etc. It is not as much a matter of position but of the inner kinesthetic feeling and directions: What remains the same is their freedom of movement and being in balance.

Techniques and Exercises*

• Ask a student to push you while you resist the push, staying stiff and not allowing yourself to move from your spot. Now ask again, but be flexible and allow yourself to move. This will help convey the concept of how releasing can allow movement.

• Imagine that the top of the head is being pulled up gently from a string. Allow that direction to lead the head, neck and spine. Lengthen and widen the body in all directions; experience a lightness, as if the body is moving itself. Simultaneously, feel the gravity and the weight of the body going down.

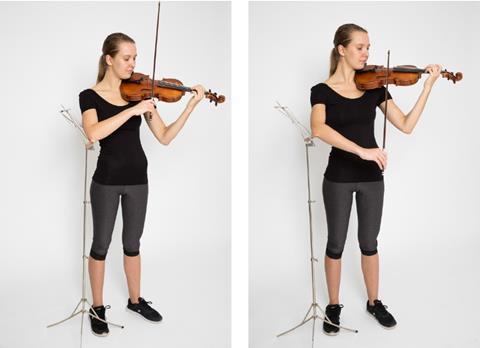

• Raise and let your shoulders fall, like a coat hanging from a hanger.

• Raise your arms and let them fall making sure you are not holding while they fall.

• Have the teacher take the student’s hand and move it in any direction. Allow the movement without any interference.

• Rotate your head and move in all different directions while playing.

• Leave your jaw loose, don’t crunch your teeth, practise with an open mouth, or put a cookie between your teeth.

• Lean the left elbow on a piano or stand. Let go of the weight of the arm and enjoy the support. Ask someone to hold your arm and let the weight go.

• Have someone support your instrument at the scroll and practice feeling the weight of your arm hanging off of the fingerboard by your fingers.

• Especially release tension in the moment of shifting up. Practice arpeggios with one finger, releasing before and during every shift. Practice shifts with your elbow on a piano or held by your teacher.

• Release your left thumb every once in a while to make sure it’s relaxed.

• Squeeze around the right armpit with your left hand. Move your arm in all direction to check that the muscles your hand is squeezing don’t contract involuntarily.

• Move your forearm to make sure the hinge of the elbow is loose.

• Hang a bag on your right shoulder to make sure it doesn’t tense up. You can also use the image of a warm, dripping wet towel hanging from the shoulder.

• Move your forearm to make sure the hinge of the elbow is loose.

• Place you right elbow on a piano or stand. Enjoy not needing to hold up your arm. Move your forearm freely.

• Hold the bow from the screw with the thumb, index, and middle fingers. Release your weight into your legs in order to get a good sound without adding any pressure.

• Grab your bow with your full hand and play. Now, do it holding the bow with your middle phalanxes. Now go to your 'normal’ holding position. The idea is to hold the bow in a fancy-free way, allowing the energy to flow through your lower back, shoulder, arm, forearm, hand, and fingers, to the bow to the string.

• Squat with your back against a wall. Feel all the weight on the soles of your feet. Your thighs will be working hard to hold your weight, your gluteus will be relaxed, and your lower back and torso will be flat against the wall without an arch. Realise how your sound opens up and your instrument resonates better with no effort.

• Lie on the floor. Feel your shoulder blades resting on the floor. Any superfluous tension in the head, neck and shoulder blade will become noticeable. Feel your lower back touching the floor and your hips completely free.

Eventually you need to integrate all these new kinesthetic feelings into a sensation for the whole body. Find an image or a couple of words that help you recalling that feeling when you play. Doing this ultimately helps us to free our movements, feel physically better, and channel all of our energy into producing a beautiful sound, allowing nothing to interfere with the music.

*Some exercises might not be suitable for everyone. Before attempting a new exercise, take into account factors such as flexibility, strength and overall health to determine whether or not a particular exercise is appropriate for you. The following, like any physical exercises, are inherently dangerous and can result in personal injury or damage to the instrument and/or bow. Any injury sustained from the proper or improper use of these exercises is solely the responsibility of the person who follows the exercises. Tomas Cotik and his partners disclaim any liability from injury or damages to the instrument and/or bow caused from the use of these exercises and suggest first consulting an experienced string teacher or Alexander Technique instructor.

A full article on this topic is available here.

Some concepts are described in greater depth in the following articles:

• William Conable, 'The Alexander Technique', Journal of the Violin Society of America 13, no. 1 (1993), 126-132.

• Charles Jay Stein, 'The Alexander Technique: Its Basic Principles Applied to the Teaching and Performing of Stringed Instruments', American String Teacher, 49:3 (August 1999), 75-77.

Dr Tomas Cotik currently teaches at University of Miami’s Frost School of Music and Florida International University. He regularly gives masterclasses and lectures throughout the country. Hailed by Michael Tilson Thomas as 'an excellent violinist', Tomas Cotik was a first-prize winner at the National Broadcast Music Competition in his native Argentina in 1997, and the winner of the Government of Canada Award for 2003-2005. A prolific recording artist, Dr Cotik is currently involved with more than a dozen CDs, which include Schubert’s complete works for violin and piano and Mozart’s 16 sonatas. A former rotating concertmaster of the New World Symphony, Cotik has worked closely with members of the Cleveland, Miami, Pro Arte, Vogler, Vermeer, Tokyo and Endellion String Quartets. Dr Cotik is a currently a member of the Amernet String Quartet and the Cotik/Lin duo.

Photos: So-Ming Kang

Student, model, and assistant: Patricia Jancova

No comments yet