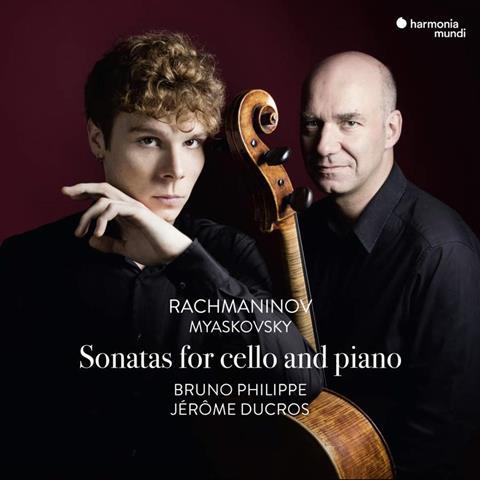

This month, young French cellist Bruno Philippe releases his first album as an official Harmonia Mundi artist. In this extract from our February cover story, he chats with Charlotte Gardner about the merits of gut strings

This is an extract of a longer article in The Strad’s February 2019 issue. To read in full, download the magazine now on desktop computer or via the The Strad App, or buy the print edition

‘Never lose the first impression that has moved you.’ So said the French 19th-century landscape painter Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot once upon a time, and his words have been feeling both wonderfully relevant and wonderfully inadequate as I’ve mulled over my first two encounters with Bruno Philippe.

The first of these took place one year ago at Switzerland’s Sommets Musicaux de Gstaad festival, and everything about it was big and joyous: a recital in which he was partnered by pianist Jérôme Ducros whose central performance of the Rachmaninoff Cello Sonata was of such truthful passion and beauty that it prompted two involuntary mid-work rounds of applause from an audience unable to help themselves; then the warmest and most merry of interviews over which a glowing Philippe – on a complete post-concert high, with cigarette in one waving hand and a pint in the other – revealed he has an opinion worth hearing on pretty much everything. It moved me.

playing on gut strings really helps you when returning to modern ones, because you’re feeling things so differently in your body

It was also a softer Philippe, albeit an equally glowing one, who sat down with me in a café in the Place du Châtelet. The conversation begins with him confirming that the previous night, playing Vivaldi with Ensemble Jupiter, had constituted a new string to his concert bow.

‘I used gut when I was at the Paris Conservatoire to work a bit with Christophe Coin,’ he says, ‘but this was the first time I’d done an entire concert on it. In fact, when Thomas first invited me it was to play a concerto, but when he then asked whether it would be OK for me also to play continuo, I was interested in giving it a shot. I’ve always had a lot of admiration for Baroque players. We all do the same job, but they manage so many different things.

Working with gut strings gives you much more humility about playing in tune, for instance. There’s also the difficulty of finding a way to make the music breathe together as an ensemble, with different bows and ways of shaping a phrase. Plus, it’s strange, but playing on gut strings really helps you when returning to modern ones, because you’re feeling things so differently in your body: the gut string doesn’t sound if you have a lot of tension in your right arm, so when you go back to steel you release and get even more sound.’

He continues: ‘Another thing is that you see the way the cello’s role has evolved over the centuries. So it’s been a good experience for me, and I strongly believe that as cellists we should all try to do this at some point. I also love the repertoire. The Vivaldi we played yesterday – of course, it’s Baroque, but it’s so romantic. It really comes from the heart – from the stomach – of the composer.’

To read the full article in our February 2019 issue, download the magazine now on desktop computer or via the The Strad App, or buy the print edition

Bruno Philippe’s new recording for Harmonia Mundi features cello sonatas by Rachmaninoff and Myaskovsky.

The Strad has ten copies of Philippe’s CD to be won, and for your chance to receive a copy, simply click here to enter your details.

Closing date 31 March 2019

Reference

No comments yet