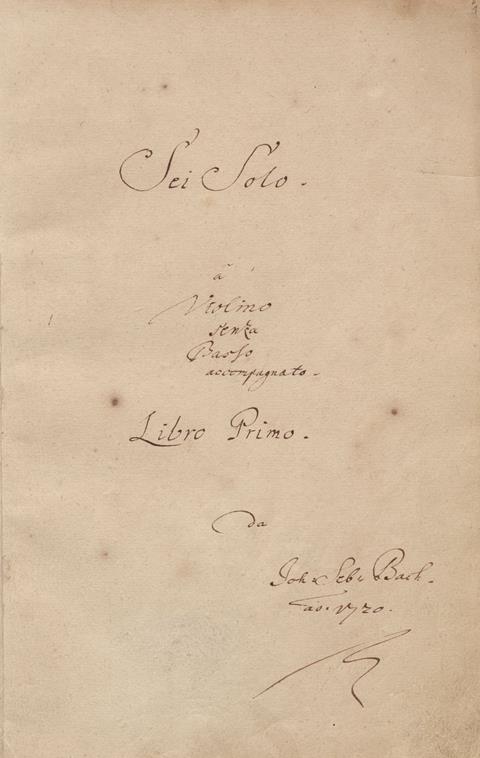

In this extract from the July 2021 issue, Lewis Kaplan, senior member of the Juilliard School faculty, introduces his discussion of character and interpretation of Bach’s three sonatas for solo violin

The following extract is from The Strad’s July issue on J.S. Bach’s Solo Violin Sonatas. To read it in full, click here to subscribe and login. The July 2021 digital magazine and print edition are on sale now.

From the late 19th century and through most of the 20th, the interpretation of Bach’s Sonatas and Partitas seems to have been premised on the fact that Bach was a great composer and therefore the playing had to be impressive, heavy, dominating and ultra-serious, with an emphasis on big sound and melody. Of course it was up to us, the performers, to make Bach great, yet consideration of harmony and rhythm was almost non-existent, despite the fact that the composer’s biographers over two centuries had spoken with insight and emphasis about Bach’s harmonic genius. Something that had a powerful impact on me personally was reading that Beethoven, in a letter to one of his publishers, described Bach as the ‘father of harmony’.

This century-long concept of Bach performance began to change with the awakening of the enlightened concept of playing in Baroque style, mostly on so-called original instruments. The major changes were in sound and articulation – harmony, as always, depended on the imagination and ear of the individual. But the fact that instruments were tuned to a frequency of 415Hz did not by any means assure a profound interpretation.

With each of the three sonatas, I believe that Bach began with the fugue and built the outer movements around it. Each fugue has a clear character: playfulness in no.1 in G minor BWV1001; humour in no.2 in A minor BWV1003; and a religious quality in no.3 in C major BWV1005.

The breadth of what Bach does with each four-movement sonata is enormous. The opening movements are introductions to the fugues. These are followed by the fugue itself, which, of course, develops an idea or subject. The character of each fugue is prepared by the preceding slow movement, so the two are obviously linked. The third movements have remarkable individuality – BWV1001’s Siciliana being a conversation between three voices, the Andante of BWV1003 an aria with a heartbeat ostinato, and the Largo of BWV1005 an aria of touching simplicity with barely any accompaniment. The final movements are celebrations with virtuosic displays. Bach himself was a virtuoso composer and organist, and given the age in which he lived, he probably would have been considered a virtuoso string player as well. However, the virtuosic aspect never dominates in his music. Technique is always used to demonstrate an emotion, an idea or a character; the music is never just a showy display.

Read: Bach Solo Violin Sonatas: At heart a fugue

-

This article was published in the July 2021 Carlo Bergonzi ‘Baron Knoop’ issue

Micro-CT scanning technology reveals the secrets of the 1735 Carol Bergonzi ‘Baron Knoop’ violin. Explore all the articles in this issue . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- 1735 Carol Bergonzi ‘Baron Knoop’ violin

- Bach Solo Violin Sonatas

- Villa-Lobos and the cello

- Violist Timothy Ridout on recording Schumann and Prokofiev

- Violin Making schools in China

- Tribute to British cellist Marius May

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet