Harriet Smith takes a boat deep into Norway’s west-coast waterways to experience a Beethoven-inspired festival held in a spectacular setting

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Read more premium content for subscribers here

The Rosendal Chamber Music Festival has been on my bucket list ever since I first heard about it. It was launched in 2016 by Norwegian pianist Leif Ove Andsnes, whose notion of gathering friends together to make music in a spot just remote enough to make getting there feel like an adventure was irresistible. From the UK this involves a flight to Bergen, from where two boats a day take you through the Hardangerfjord to Rosendal, a trip of some 90 minutes. Waiting on the jetty when I arrived was Icelandic pianist Víkingur Ólafsson with his three-year-old son, natty in coordinated knitwear: it set the scene and somehow boded well.

The setting was as picturesque as I’d imagined, but it was a rugged and tough beauty: the Folgefonna glaciers in the distance, the immediate backdrop to the music making being waterfall-clothed mountains. It was, if it’s not too far-fetched, a Beethovenian kind of landscape – the sort of place you could imagine him striding through while wrestling with fugal thoughts.

The two main venues couldn’t have appeared more different. There’s the traditional Kvinnherad Church, a 13th-century whitewashed building that is outwardly austere but inside is beautifully decorated, with hand-painted stars on its ceiling from which is suspended an ornamental wooden ship – a timely reminder of the seagoing nature of these peoples. By contrast, there’s the optimistically named Great Hall, which started life as an A-frame barn that only works acoustically thanks to some major audio trickery from a system named Constellation by Meyer Sound of Berkeley, California; I was initially sceptical, but it’s amazing how fast the ear adjusts. Both are part of the Baroniet Rosendal Manor House estate, where Andsnes has been performing for more than two decades. Being able to wander through the ancient rooms and the estate’s perfectly kept rose garden and potager were yet more pleasures given to festival-goers.

Read: Hybrid model: Postcard from Trondheim

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Read more premium content for subscribers here

This year was a delayed celebration of Beethoven’s anniversary, from the cancelled 2020 festival. Alongside the birthday boy were featured two Bergen-born Norwegians: composer Ketil Hvoslef, now in his eighties; and from a younger generation, the jazz saxophonist and composer Marius Neset. Hvoslef’s Hardingtrio opened the first concert and immediately drew us into a folk-tinged world, with particularly evocative playing from Håkon Asheim on the Hardanger fiddle. And how naturally this sat alongside Beethoven’s ‘Kreutzer’ Sonata, performed with superb reactivity by Antje Weithaas and Enrico Pace.

From that point on, I was reminded of just why short festivals appeal so much. This was four days of intense music making (7–10 July), featuring ten concerts plus talks and conversations among which for English speakers there was American composer and writer Jan Swafford, who hid his considerable learning under an avuncular cloak, while Norwegian speakers took advantage of pre-concert lectures by pianist Gunilla Süssmann. Perhaps best of all was a Q&A on the final day with musicians from the festival discussing their personal relationships with Beethoven in the most egalitarian way. And that rather summed up the festival as a whole: it may have been stuffed with star musicians (the fact that Steven Isserlis was a late stand-in for the Covid-stricken Tanja Tetzlaff says much about the level), but it had a relaxed vibe that allowed them to bloom.

The Van Kuijk Quartet formed a leitmotif over the festival, presenting no fewer than five Beethoven quartets as well as Hvoslef’s Third. The programmes ambitiously ranged from op.18 no.6 to op.135, taking in op.95 along the way, but the quartet began with the first of the Rasumovskys and made its final appearance with op.59 no.3. This French group entered into the very different worlds of early, middle and late Beethoven with aplomb; if the two most characterful players here are the violist and cellist, that’s not to diminish them as an ensemble whose sense of finesse was everywhere apparent. At times, that triumphed over tension (in op.59 no.3, for instance), and op.135 didn’t quite achieve the transcendence that it can, but there’s no doubting the promise of a group still in its infancy in quartet terms.

It was a Beethovenian kind of landscape – the sort of place you could imagine him striding through while wrestling with fugal thoughts

One of the joys of a festival of this kind is the ability to programme in a way that might be deemed uncommercial in major concert halls. The late-evening concert on the penultimate day was a case in point, counterpointing less-often heard works by Beethoven such as the Fantasia op.77 for piano (from the tireless Pace) and the Variations on ‘Bei Männern, welche Liebe fühlen’ (rendered uproariously characterful by Isserlis and Sveinung Bjelland), plus bagatelles played by Andsnes himself on a c.1860 Pleyel fortepiano discovered among the collection in the manor house and beautifully brought back to life. Interspersed were two works – by turns sinuous and virtuoso – by Neset, and the music making ended with Hvoslef’s Third String Quartet, played with real authority by the Van Kuijk.

The fortepiano also rather stole the show in a concert for which Kristian Bezuidenhout dropped in to perform Beethoven’s last violin sonata with Alina Ibragimova – a masterclass in the subtlest of tinta and the kind of reactivity that comes from the finest partnerships, and one that was found in equal measure in Isserlis and Andsnes’s fantasy-rich account of Beethoven’s penultimate cello sonata. I’d not heard them perform together before, but they appeared very much on the same wavelength. So too were the players in Beethoven’s Septet op.20, with Andsnes and his three children sitting spellbound while his horn player wife Ragnhild Lothe joined her colleagues on stage.

Beethoven’s piano trios were not forgotten either: particularly notable were the opener and closer to the last day’s music making, with Andsnes, Ibragimova and Audun Sandvik making a particularly compelling case for op.1 no.3 in the morning, and Pace, Ibragimova and Christian Poltéra closing the festival in riveting fashion in op.70 no.2. If the ‘Archduke’ from Ólafsson, Weithaas and Isserlis was slightly less convincing, it was apparently the first time the pianist had tackled the monstrous keyboard part; elsewhere in the festival, though, he proved his versatility in compelling readings of Mozart and Beethoven sonatas and, best of all, in duets with Andsnes in music by Beethoven via Czerny and Bach via György Kurtág.

In among the Beethoven of the closing concert was featured a commission from Neset: Who We Are, a pertinent title for a piece written in Covid-haunted 2020. We already seem to have moved far from those dark days. I may have had unreasonably high expectations of this festival, but they were more than met. Anyone who could fail to be enchanted by such music making in this glorious setting is surely short in the soul department.

Read: Steven Isserlis: Instinctive performer

Listen: The Strad Podcast Episode #38: Eldbjørg Hemsing on Norwegian music

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Read more premium content for subscribers here

-

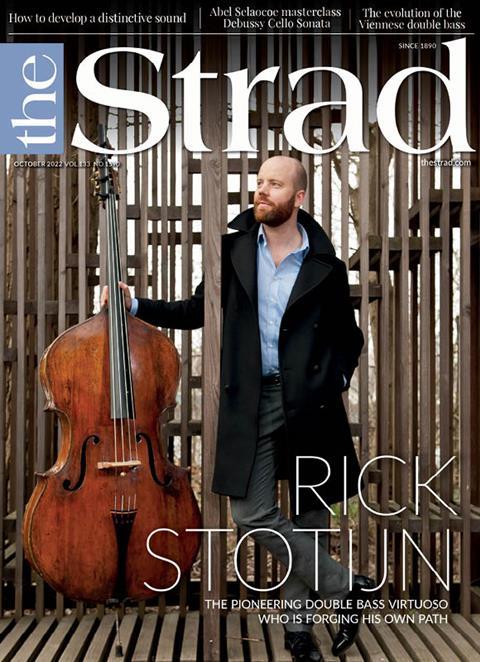

This article was published in the October 2022 Rick Stotijn issue.

The Dutch double bassist is on a continual quest for original repertoire for his instrument. He tells Kimon Daltas about his new album and collaborative work. Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- Rick Stotijn

- The Viennese Double Bass

- Scottish Fiddle Dance Music

- Rachel Barton Pine

- Developing your own sound

- The Strad Calendar 2023

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet