Half a century since the New York Phil hired its first black musician, the percentage of black and Latino players in US orchestras remains woefully low. But some organisations are taking action towards inclusivity

Please note, this article was first published in the November 2014 issue of The Strad so some of the interviewees may no longer hold the positions described here and some statistics will be out of date

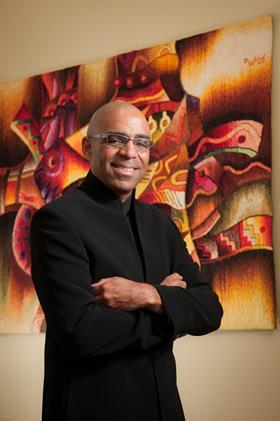

In a strongly worded address at Carnegie Hall in New York in October 2013, Aaron Dworkin – who founded the non-profit Sphinx Organization in 1996 to advocate for black and Latino classical musicians – lamented the paucity of those minorities in major orchestras nationwide. When it came to inclusivity initiatives, he said, orchestras lagged behind almost every other industry in the US. ‘In 2013, there are only three orchestras – Detroit, Baltimore and Pittsburgh – with an active formal fellowship programme.’ More than 50 years after Leonard Bernstein appointed the violinist Sanford Allen as the first black member of the New York Philharmonic, the orchestra had not a single African–American or Latino player among its ranks.

Since that speech, the African–American clarinettist Anthony McGill, formerly a member of New York’s Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, has been appointed section leader of the Philharmonic. But the statistics remain discouraging. The trumpeter Tage Larsen, who was hired by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 2002, remains its only black member today. There is also just one Latino player. Ann Hobson Pilot, who retired in 2009 as principal harpist of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, was the first (and only) African–American woman in the ensemble, a situation that remains.

In 1968, the year Martin Luther King was assassinated, Henry Lewis was appointed music director of the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra, the first black person to head a major American orchestra. But there are currently no black directors of major American orchestras. Only about 4.2 per cent of musicians in orchestras nationwide are black and Latino (the figure was 2.1 per cent in 2002). Fewer than 0.5 per cent of executive directors are either Latino or black, and less than one per cent of works performed by orchestras are written by members of those minorities. And ever since the contralto Marian Anderson made her Metropolitan Opera debut in 1955, African–Americans have been better represented on the opera stage than their counterparts in the orchestra pit – a statistic noted on the website of Colour of Music, a festival that highlights music written by black composers and features African–American performers, which debuted in Charleston, South Carolina, last year.

To combat the disparity, Dworkin urges conductors and administrators to follow Bernstein’s example and take steps to identify orchestral candidates of colour. Dworkin, who recalls that he was mocked for his Afro hairstyle during his time as concertmaster of a Pennsylvania youth orchestra, points out that no major American orchestra has ever contacted him to announce auditions or solicit referrals for promising candidates. His own organisation provides free instruments and training to minority musicians, and runs an annual competition for Latino and black string players, and he suggests that orchestras allocate a percentage of their budgets to inclusion initiatives. ‘I don’t believe that today there is active prejudice practised by leaders in our sector, but there is a profound sound of silence,’ he says.

There is, of course, a history of ‘active prejudice’ in America’s troubled past, when as late as the mid-1960s some concert halls were still segregated. In 1964 the pianist Gary Graffman cancelled a booking in Jackson, Mississippi, after discovering that seating in the house was segregated; other prominent classical artists soon followed his example. Before a 1961 concert in Birmingham, Alabama, city officials attempted to stop the African–American cellist Donald White, at the time a member of the Cleveland Orchestra, from performing. The concert went ahead only because George Szell, who had hired White, threatened to cancel the sold-out event.

The violinist Eddie Drennon, a member of the Washington DC-based Umoja Quartet, recalls auditioning for bands in the US Navy and Marines shortly after a desegregation order in the early 1960s from President Kennedy (whose Catholic faith had attracted hostility from those unwilling to shift away from the Protestant status quo). When Drennon called to enquire about the results of his tryouts, he was told that he ‘wouldn’t be comfortable’ in the ensembles. ‘That was my final attempt to play classical music,’ he says, although he had a stint with the Richmond Symphony Orchestra in the 1970s. He notes that his African–American classical colleagues were faring much better in Europe at the time.

Sanford Allen says he never felt ‘comfortable’ playing with the Philharmonic. ‘If the orchestra was on tour, there were times I could see people obviously discussing my presence; sometimes it would degenerate to the point of finger-pointing. That has a limited shelf life as an experience.’ He points out that at the time there were also no female members: ‘There were periodically disagreements between me and some of the other players, as they thought that I should support the idea of not hiring women. It seemed to me that the reasons they were giving for not hiring women were the same reasons that I shouldn’t have been hired.’

‘The most effective tool for diversifying the audience is having a diverse group of people on stage’ – Jeri Lynne Johnson

Jeri Lynne Johnson founded the Black Pearl Chamber Orchestra – comprising graduates of Juilliard, Curtis and other top conservatoires and evenly split between black, Asian, white and Latino musicians – in 2007, shortly after being rejected for a conducting position with an ensemble in California. She learnt from a board member that her talent had been recognised but that administrators ‘didn’t know how to market’ her. When she asked for clarification, the board member responded, ‘You don’t look like what our audience expects a conductor to look like.’ Instead of pursuing legal action for discrimination, Johnson says she appreciated his honesty and decided to prove him wrong by creating her own group. ‘I could have gone on thinking, “I am not talented enough,”’ she says. ‘To hear that it had nothing to do with my talent was encouraging. Most classical organisations tend to be homogenous, older, and with not many people of colour. It tends to skew towards a particular segment of society.’

Johnson points out that 2007, the year she was rejected as ‘unmarketable’, was just one year before Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton ran for office. ‘The sea change of that election was that people’s image of leadership was widening. It could be a white woman or an African–American man. It didn’t have to be an old European white man.’ She adds that in her experience, creating a more inclusive orchestra was simply good business sense: ‘The medium is the message. Even if your orchestra is doing a lot of great things in the community, if the community doesn’t see itself reflected in your organisation, the organisation will still seem like an outsider. Quality and diversity are not these mutually exclusive ideas; diversity is good business. There are so many people who may have never heard a Beethoven symphony live,’ she says. ‘Coca-Cola doesn’t say, “We want to sell Coke only to people who already drink Coke.”’

Johnson says she knows Black Pearl is reaching new audiences when there is energetic clapping between movements. She sees this as a sign of the audience interacting with the ensemble. ‘For us at Black Pearl, the single most effective tool for diversifying the audience for classical music is having a diverse group of people on stage,’ she says.

Despite the need for greater diversity, the question of affirmative action remains as controversial now as it was in 1989, when a crisis erupted at the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. The Michigan legislature withheld substantial state funds and demanded that the ensemble – which then had two black members in a city that was more than 60 per cent black – must immediately hire more black musicians. The orchestra abandoned its rigorous audition process to expedite the hiring. That in turn frustrated minority musicians (including those hired), who were concerned they would be disparaged for receiving special privileges instead of respected for their abilities.

Melissa White, a violinist with the Harlem Quartet, whose members are graduates of Sphinx programmes, says a candidate recruited because of his or her race will ‘always be under a magnifying glass’. Indeed, Allen, who had played regularly with the Philharmonic as a sub before being appointed as a full-time member, resigned in 1977 in part because he was tired of being a symbol.

‘I seemed to have a kind of double-edged symbolism,’ he says. ‘One group felt that integration had been accomplished because I was there. That was countered by an equally vociferous group who said you couldn’t define it as “integration” if I was the only one there. Any time a black or Latino person does anything that the majority construes as being out of the ordinary, you wind up in a spotlight situation immediately.’

To avoid putting minority candidates in a position where they might be accused of receiving special favours, both Johnson and White advocate maintaining the anonymity that some say is a crucial part of orchestral auditions. However, they also recommend extending efforts to make sure that minority candidates can get behind the screens in the first place.

‘If the orchestra doesn’t represent the community, it won’t be supported. That goes hand in hand with accessibility’ – Robin Massie-Pighee

Considering that musicians start studying their instruments when still at their mother’s knee, these efforts need to begin early on. Racial and socio-economic issues are often inseparable – issues of class can have an impact on success as much in the classical music field as in any other highly competitive industry. Children from privileged backgrounds (often white) have better access to the private teachers, competitions and expensive summer camps that are vital to building a network and fostering success. The issue has become even more prevalent since music education was slashed from so many public school systems nationwide. A 2011 survey for the National Endowment for the Arts revealed a 5 per cent decline in the rate of arts education for white children between 1982 and 2008, whereas the decline among African–American children across the same period was 49 per cent, and among Hispanic children, 40 per cent.

The Harmony Foundation in New York City, founded by woodwind teacher Anne Fitzgibbon after she spent time in Venezuela studying the El Sistema model, is one grassroots organisation whose work is going some way to filling the void. Harmony provides instruments and tuition free of charge to disadvantaged children in New York, and 90 per cent of the programme’s students are Latino and black.

‘One of our goals is to reach these kids and give them an entry into ensembles they wouldn’t otherwise be part of,’ says Fitzgibbon. ‘Our young people have had opportunities to play with world-famous musicians. They are too young to be intimidated and I want them to hold on to that – they are so excited about becoming classical musicians. The only reason we don’t see more diversity is because of a lack of opportunity, a lack of exposure and familiarity. If you don’t get the start at the beginning, those opportunities don’t exist for you. We are trying to be the leg up.’

Some orchestras have programmes to nurture gifted young minorities, including the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, whose Talent Development Program, founded by civil rights activist Azira Hill, has helped young Latino and African–American musicians secure spots in top conservatoires. Among its outreach and education programmes, the Baltimore Symphony offers an annual fellowship to a young African–American string player, who get to perform with the orchestra, receive extensive audition preparation, and are mentored by a section musician and the orchestra’s music director, Marin Alsop. The Chicago Sinfonietta, founded by Paul Freeman in 1987 with the mission to better reflect the cultural make-up of the community, operates extensive programmes in Chicago public schools and mentors young professionals through its ‘Project Inclusion’.

‘Opportunity is the beginning of success,’ says Robin Massie-Pighee, assistant principal viola with the Delaware Symphony Orchestra and co-principal viola with Black Pearl. ‘If you don’t have the opportunities, how can you prepare yourself for a career? We have to support each other and musicians coming up behind us: we have to keep the art alive. But if the orchestra doesn’t represent the community, it won’t be supported. That goes hand in hand with accessibility.’

Dworkin concluded his Carnegie Hall speech with a call to action: for American orchestras to commit five per cent or more of their budget to inclusion initiatives; and for arts grant makers to require orchestras to have an inclusion plan in place in order to be eligible for funding. ‘Bernstein implemented a policy whereby every time a position opened, the orchestra reached out to candidates of colour,’ he said. In February 2015 the international convention on diversity in performing arts, SphinxCon, will be held in Detroit, and the issues and challenges will be thrashed out in public and online at SphinxCon.org. Bernstein’s example may yet prove to be the touch paper for reform after all.

2 Readers' comments