Pianist Diana Ambache explains how she came to set up the Ambache Charitable Trust with proceeds from the sale of a 1735 Guarneri del Gesù violin, discovered in her late father's collection

My father Dr Nachman Ambache was a research scientist who was also an amateur collector of stringed instruments. His interest encouraged him to visit auction sales and musical gypsies in search of rare finds. Throughout 50 years of collecting, he sustained the enthusiasm and belief that one of his discoveries would turn out to be a Strad or similarly precious Italian instrument. He was generally disappointed when his excitement about his latest acquisition was met with my ignorant response.

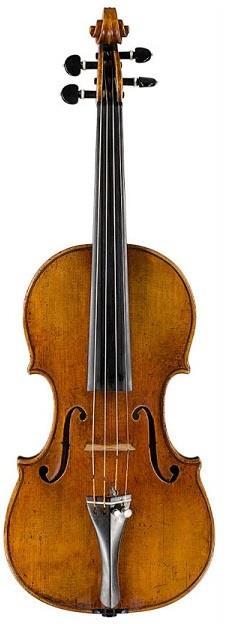

After my father’s death, my family asked Peter Horner of Brompton’s Auctioneers to assess his collection and to our surprise Peter confirmed that one of my father's acquisitions was indeed a rare gem – not a Strad but a 1735 Guarneri 'del Gesù' (below). My father had that characteristic mix of excitement and nerves, which made him reluctant to consult the authorities about his instruments, so I thought of how delighted he would have been to have had his hunch confirmed - not least as he had bought the violin at a Sotheby’s sale in 1975.

London dealer Peter Biddulph authenticated the instrument in 2007, and undertook its restoration. We subsequently lent the violin to the Vienna Philharmonic, and eventually sold it to a violinist, director and former pupil of Isaac Stern, who now performs on it for audiences who appreciate the instrument at the highest level. It is thought that a previous owner was the violinist and composer Giovanni Battista Viotti.

I started the Ambache Charitable Trust in 2013 to raise the profile of music by women. As founder of the Ambache Chamber Orchestra, which performed for 24 years from 1984 to 2008, I had championed the music of women composers from the last three centuries through concerts and recordings (womenofnote.co.uk). Now with my share from the violin sale, I was in the position to promote a richer appreciation of female composers, past and present.

Over the last four years the Ambache Charitable Trust has supported projects promoting female composers to the widest possible circle; these have included concert tours, concert series, festivals, new CDs, typesetting scores, a conference on women’s work, and an online catalogue of music.

While living composers are here to network and promote themselves, the dead are unable to do so, and therefore need contemporary champions. Everyone was thrilled when The Guardian included the Brighton Early Music Festival as one of its ten best cultural events of 2015; their tongue-in-cheek production of Francesca Caccini’s La Liberazione di Ruggiero was delightfully entertaining. There has also been a London Festival of Baroque Music featuring Barbara Strozzi, Isabella Leonarda and Élisabeth Claude Jacquet de la Guerre.

Organisations who’ve promoted this music have ranged from the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra and the London Philharmonic Orchestra to an enterprising Canadian Ensemble, who premiered Barbara Pentland’s 1950s opera The Lake. Continuing round the world, our National Youth Choirs of Great Britain took music by Kerry Andrews and Vikki Stone on their Far East tour.

Back on home ground, regional music clubs have featured and commissioned works by women; an enterprising plan links Scottish women of science with Scottish composers at Edinburgh Fringe Festival; another linking project is Fenella Humphreys’ 'Bach to the Future', with six commissions to accompany Bach’s Sonatas and Partitas. The 2014 Women of the World Festival included string quartets by Germaine Tailleferre and Vítezslava Kaprálová.

CDs are valuable for their ongoing life, and the trust has contributed to around ten releases thus far. Again, the span is wide, including Hyperion’s first collection of Romantic Piano Concertos by women (Amy Beach, Cécile Chaminade and Dorothy Howell), the first complete recording of Ethel Smyth’s The Boatswain’s Mate, and my own latest recording of chamber music by international violinist Grazyna Bacewicz, which includes colourful folk-inspired dances, her quirky, witty and exciting Quartet for Four Violins and the pungent, vibrant Quartet for Four Cellos. It’s heartening to know that a violin is playing its part in supporting a composer posthumously and I hope this will spur on others to discover Bacewicz’s music.

No comments yet