Ahead of his 2020 album release of Bach’s Sonatas and Partitas, the violinist continues his blog series, in which he discusses the contradictions between the opposing trends and traditions in Bach interpretation, and his personal solutions to them

In his last instalment, Tomás Cotik discussed the context of composition of Bach’s Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin, the title ‘Sei Solo’ and Editions. This week he focuses on Treatises Sources, Numerology and the Doctrine of Affections.

Treatises Sources

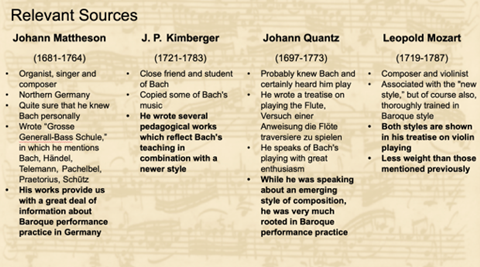

The following tables display sources that can help us understand the performance style as described by Anthony Newman. The first are arguably the most important for Bach.

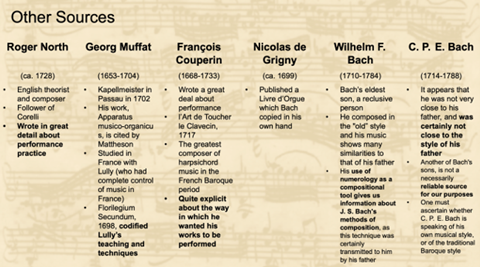

Muffat and Couperin’s treatises apply more specifically to French music. We should consider also that C.P.E. Bach’s style and that of his father were significantly different, and his writings might not help us that much in understanding Johann Sebastian’s music.

Numerology

Long before Bach, composers applied the principles of numerology, or numeric symbolism, to their compositions. Bach was likely familiar with the writings of Andreas Werckmeister, a German organist, music theorist, and composer, who outlined the use and significance of numbers in music. Examples of numerology in Bach’s works can be found in the attention to the numbers 14 (the sum of the letters in ‘BACH’ = 2+1+3+8) and 41 (reverse of 14 as well as the sum after the addition of his initials, ‘J’ and ‘S’). Bach appears to also recurrently use the numbers 21, 23, and 55 of the Fibonacci series. Bach’s contemporaries, Buxtehude, Mattheson and Händel, also included number symbolism in their compositions.

There are complete books that deal with numerology and its supposed discoveries in Bach’s music in addition to fanciful speculation and possible theological references. It remains a somewhat controversial topic, certainly raising the question of how much numeric symbolism translates into relevant audible information.

Doctrine of Affections

Baroque theorists and composers believed that music was capable of arousing a variety of specific emotions within the listener. The German ‘Affektenlehre,’ or theory of musical aesthetics, was widely cataloged and described by theorists such as Athanasius Kircher, Andreas Werckmeister, Johann David Heinichen, and Johann Mattheson during the 17th and 18th centuries. This theory proposed that by making use of the proper standard musical procedure or device, the composer could create music capable of producing a particular involuntary emotional response in the listener.

Many of Bach’s movements adhere to the idea of one affect per movement. While we are not seeking the kind of expressive changes in color, dynamic, and mood that are characteristic of the Romantic Era, we are looking instead to capture the overarching spirit and essence of the dance, fugal subject, etc. presented in the movement as a whole. Of course, this does not mean that we do not acknowledge the harmonic changes or the different sections in the longer movements (e.g. in the fugues or the Chaconne).

Next week, Tomás Cotik concentrates on Traditions and Musical Lineage, ‘Interpretation’, Performance Environment and the Recording Process.

Tomás Cotik performs Bach’s Chaconne

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

Currently reading

Currently readingHow I interpret Bach: Tomás Cotik on Treatises Sources, Numerology and the Doctrine of Affections

- 11

No comments yet