Revisit our most popular lutherie articles from 2022

Readers of The Strad are clearly fascinated by the world of violin making; from the world’s priciest violin, to straightforward tips on looking after your instrument, to superstar David Garrett’s frantic adventure acquiring a ‘del Gesù’ violin. For each of the twelve days of Christmas, take a look at our most-viewed lutherie articles from 2022 - perfect if you’re after some holiday reading. Click the headlines to read the full article. Enjoy!

Discover more lutherie articles here

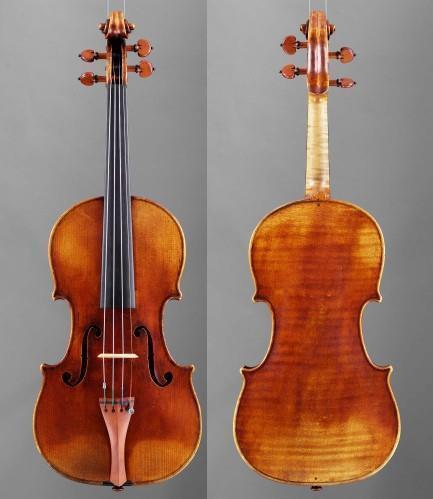

Photo courtesy: J.&A. Beare Ltd

The scroll of the ‘Vieuxtemps’ is bold without appearing bulky

The world’s most expensive violin: the 1741 ‘Vieuxtemps’ Guarneri ‘del Gesù’

’In many of the instruments of GdG there is little or no colouration added to the varnish. One could feasibly make the argument that the varnish itself was not very expensive (and was probably the same as that used by cabinet makers and other artisans) but the colour red was expensive and reserved for instruments that were not built on speculation but had an intended buyer, so the maker could recoup the cost upon sale. For a maker such as Stradivari this wouldn’t have been an issue since the vast majority of his instruments were commissioned, but for a maker with limited resources this could have been a significant consideration.’

My whirlwind journey to owning a Guarneri ‘del Gesù’: David Garrett

’Without telling my friends or parents, I decided to bid on the phone. As the reception at the hotel room I was in at the time was terrible, I ran outside into the backyard, behind the parking lot, next to the huge hotel garbage cans, where it was quietest. What a place to bid on a Guarneri ‘del Gesù’!

In my mind I knew that there was no way I could go wrong paying up to €3,000,000 for this violin. My good friend and violin dealer Andreas Post confirmed that with me that morning, so I spontaneously decided to put in some bids. My last bid was €2,650,000.

My heart was racing, even though I knew this would not be a losing investment. Still, it’s a lot of money and I told the guy on the phone from the auction house that this bid would be my last.

Surely I was out of the race. Let somebody else have it, who does not sweat as much as I was doing right now, I thought. But a few seconds later, the voice on the phone said:

‘Congratulations, you just bought yourself a “del Gesù’’’.

Let me tell you, sitting next to a garbage can in an alley behind a hotel has never felt more glamorous!’

‘It was like the earth moved beneath me’ - violinist Leonidas Kavakos on playing the ’Willemotte’ Stradivari

’The ”Willemotte” is a very robust, powerful instrument, a huge model with broad f-holes, full arching and high ribs. It has a refined, perfumed kind of tone quality under the ear, yet when I hear someone else play it in a concert hall it has an incredibly complex, multidimensional character. It’s super-sensitive, and responds to everything I try to do with it. Three years after buying it, I’m still discovering a spiritual, ethereal quality to the sound, which comes from everywhere and nowhere – it’s a kind of presence that permeates everything I play. It never stops surprising me: I work on the sound non-stop, and often try different strings just to see what changes they make.’

Looking after your instrument: Fingerboards demystified

’Fingerboard wear can appear as long, thin divots running under the strings or as wavy bumps formed along the length of the board by the vibrations of the strings. Here’s a trick I teach a lot of my clients: take your instrument near a sunny window or a bright lamp. Catch the reflection of the light on the surface of your fingerboard. Carefully tilt your instrument back and forth as you sight down the board. Can you see ripples on the surface of the ebony? This is a sign that your fingerboard needs planing. Often the wear is concentrated where you play the most, ie: first position. It may not be obvious until a luthier checks it with their straight-edge.’ - Sally Mullikin

Joshua Bell on playing the ‘Huberman’ Stradivari violin

’When I first played the “Huberman”, I realised it had the most amazing combination of sweetness, power and richness – the perfect blend of all of those qualities. I was so infatuated with its sound on the day I stumbled upon it, at Charles Beare’s shop in London, that I insisted on performing on it that very same night at the Royal Albert Hall. I was playing two very demanding concertos that night, and normally I wouldn’t dream of playing on a “new” violin without weeks of adjustment, but I was so in love. Once I played a few notes on the ‘Huberman’, there was no turning back!’

Looking after your instrument: all about open seams and where to find them

’Your instrument is a dynamic structure made from an elastic material. We don’t usually think of wood this way but, as I often hear myself saying, wood moves. It responds to string tension, vibrations, weather changes, climate and player interface. Wood naturally absorbs moisture in humid conditions and releases it when the environment is dry, essentially expanding and contracting through a cycle of changes that we might not even be aware of. Most of the movement happens across the wood grain, for instance across the front and back of your instrument. Because the front and back are glued to a rib structure that is considerably more stable, the seams can be a point of tension, and when there is an overload, what happens? Pop!’ - Stacey Styles

‘Is $16 million for a violin too much to pay? Not these days’

’Is $16 million for a violin too much to pay? Not these days, especially when they can be reauctioned for twice the price. According to the Stradivari Society, in an article published in 2008, rare violins that have been sold for millions have never decreased in value and from 1960–2008 have consistently outperformed both the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) and precious metals by an enormous percentage: a 19,400% increase. By 2021 standards, their appreciation in value has seen exponential gains yet to be estimated. In other words, rare violins are a benchmark of profitability, requiring big bank notes to buy, and the Stradivarius is at the top of the chart for most serious collectors and investors.’

Looking after your instrument: the secret to bridge placement

’The bridge should be sitting level with the notches in the sound holes and the side facing the tailpiece at a ninety degree angle with the body. Most importantly the strings shouldn’t feel too resistant to pressure, or buzz against the fingerboard. Often the bridge likes to bend when you tune your instrument, so you may need to wiggle it into place; the best way to do this is to sit down and place the instrument on your lap, or for a cello or viol pop it on a table – after loosening the strings a little (not too much or you risk the soundpost falling down) hold the bridge with thumbs and forefingers and gently slide it back into an upright position so the feet are perfectly flush with the body.’ - Paris Andrew

The Strad Calendar 2023: 1784 Guadagnini violin

‘”I think it’s like a peacock in personality,” says its player, Australian String Quartet first violinist Dale Barltrop: ”spectacularly colourful, loud and proud, asserting itself with presence and command.’ It is paired with an older instrument from 1748–49, made during Guadagnini’s Piacenza period, and which has a deeper, darker sound that blends perfectly with its younger cousin.’

Looking after your instrument: a guide on caring for your bow

’As a bow maker, the first piece of advice I give out on a daily basis is to loosen your bow hair every time you have finished using it. If you play a wooden bow it is even more important to do so in order to keep the camber of the stick even. If you keep your bow hair tight all the time, you risk breakage.

When using your bow, feel how it reacts: is the mechanism working smoothly when tightening it? If not, you can take out the screw and put some dry soap on it. When you take out the screw, hold the frog onto the bow stick with one hand to keep it in place while rubbing the screw on the soap with the other.

Use a dry and clean cloth to take off the rosin and sweat from the stick and the frog on a regular basis.

Look at your bow hair: it needs to remain evenly white. Make sure to keep your hands off the hair when using the bow. When you put your fingers on the hair, it may create greasy patches. Rosin will not stick very well to those areas.’ - Suzy Schmitt

Courtesy Paul Watkins

The quartet plays in the studio of Paul Watkins’s luthier father

The value of good tools: Instruments of the Emerson Quartet

’Among the ensemble’s preferred luthiers, one figure stands tall: Samuel Zygmuntowicz in Brooklyn, New York. Setzer has owned two of the luthier’s violins. The first was a 1999 copy of the 1715”‘Pierre Rode” Stradivari (the original owned by his teacher, Oscar Shumsky), which he used for about a decade. Zygmuntowicz was pleased with the sound but later said, ”I’d like to do better for you.” Unprompted, he made a new violin for Philip Setzer’s 60th birthday in 2011, inspired by another Strad, the 1714 “Leonora Jackson”. Setzer was under no obligation to keep it, but has played it ever since. He comments on its ability to reproduce soft volume levels, and adds, ”It has a kind of Cremonese edge – the good edge that you hear in some of the great voices, like Pavarotti. It’s just beautiful, and has become more so as it’s opened up, especially the E string.” He muses, “You wonder what Sam’s instruments will sound like in a few hundred years.”’

Photo: Hiroko Umezawa/ J.&A. Beare

The front of the ‘Saveuse‘ is made from seven jointed pieces of heavy-grained spruce

Two pieces of poplar or willow make up the back of the ‘Saveuse

1726 ‘Saveuse’ Stradivari cello: Small is beautiful

’By any criteria, the “Saveuse” is a great instrument. It is the work of the greatest luthier who ever lived. That alone fulfils one of our requirements. It is a cello: more unusual and more interesting. It is a late work too, which we might expect to reveal either physical weaknesses or subtle maturity. But in Stradivari’s case, ‘a late work’ means very late. His mature period lasts from about 1720, when he was 76, to 1737, when he died aged 93, apparently still at the bench. In those years, extraordinarily, he produced two wholly new designs for the cello, and this example is of the rarer model of the two. It is so rare, in fact, that it is not acknowledged in the Hills’ book on Stradivari and is only described at any length in the revised edition of Doring’s How Many Strads?, edited and published by Bein and Fushi in 1999.’

Explore more lutherie articles here

Best of 2022: The Strad’s 12 Days of Lutherie

- 1

Currently reading

Currently readingBest of 2022: The Strad’s 12 Days of Lutherie

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

No comments yet