Barbara Khristi writes about the deeds of luthier Phillip Injeian, who helped restore instruments damaged in the Bosnian War, as well as the 2010 Haiti earthquake

Discover more lutherie articles here

War is relentless. Imagine being in the middle of a combat zone with your violin. Maybe your bridge breaks, or corners and edges break, or the neck breaks off as you have to pack up in a rush. You drop your viola. You need to run for your life while bullets are flying past you. One hits your cello while you are using it as a shield, and it saves your life (that happened). Your concert hall is bombed. You find new venues. They are ruined by shelling. You play anyway at each new venue even as you are surrounded by soldiers and violent mobs fighting in the streets. Maybe you have been wounded, but you play anyway.

When I imagine the hell of war not only for myself, it scares me that I could lose my life or even just my violin. I have never been where a war raged. I learn from others instead. We have historical examples of what war does to the music world. My revelations of the World War II Holocaust made me imagine just how many musicians are affected by war. It also gave me pause to think of current wars, and especially the neverending future wars. I found a close-up perspective in conversations with luthier, Phillip Injeian.

Injeian witnessed the damages done to the instruments of the Sarajevo Philharmonic in the war between the Bosnians and Serbians that ended in 1994. The orchestra was not unsettled by its many ethnicities. The orchestra was a family unit of instruments and their musicians. They didn’t start the war. It was politically driven entities that delivered the war. All the while, the troupe of Muslims, Croats, Serbs, Jews, and others that had played under fire, the iconic philharmonic family became a symbol of Bosnia’s multicultural ideal and its resistance to ethnic hostilities.

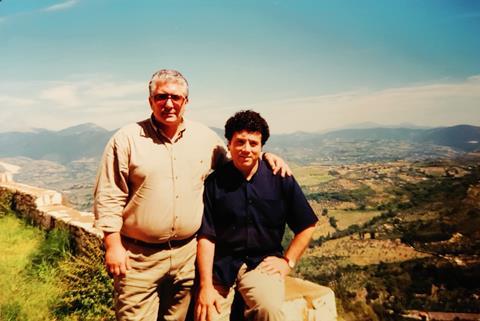

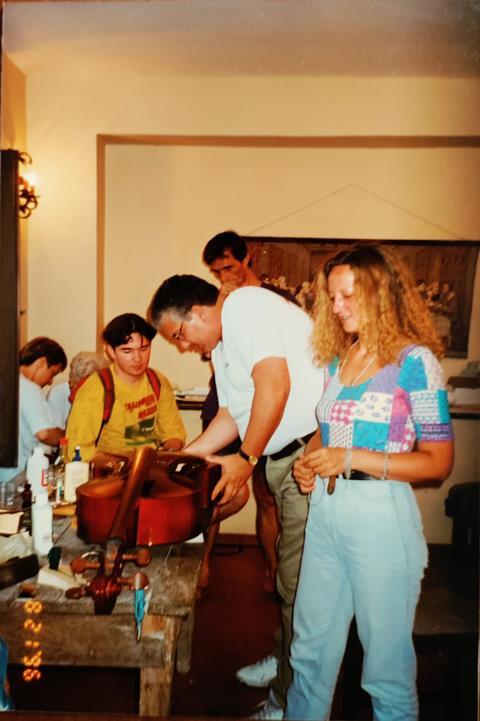

In 1996, after the war, the Sarajevo orchestra was in residence at the Farfa Giubileo Festival near Rome. Injeian went to Italy to restore its war-torn instruments. The work was done over a couple of weeks at a monastery nearby where he performed the ’surgeries.’ In Injeian’s words, ’Instruments should be treated as living beings. For the Sarajevo Philharmonic some instruments needed to be treated rather like field dressings for soldiers. Some needed more and received further restoration. Repairs were often grafts, just like skin grafts and prostheses made as are such optimal solutions for humans, according to their need.’ Injeian sees his work centered around the humanness of the instruments.

Some instruments needed to be treated rather like field dressings for soldiers

Some people wondered what he was getting out of it, how he benefited. Although he felt he was looked at suspiciously, Injeian saw himself as a typical luthier extending typical luthier generosity. Most readers of The Strad would concur that it’s not uncommon among luthiers to exhibit such noblesse oblige, the unwritten obligation of people from a noble ancestry to act honourably and generously to others. In the case of luthiers, their specialised skills and other resources of materials and their financial compassion, as such, are the wealth they bestow on musicians. A resounding example of noblesse oblige is evident in Amnon Weinstein, founder of Violins of Hope, who recently passed away leaving a great legacy to us all.

Read: Violins of Hope In Pittsburgh: Timing is everything

Read: Your violin, your legacy: the story of my violin, ‘Mrs. Evans’

A number of musicians left during Bosnian war. Injeian observed that the orchestra is now mostly young players as well as older ones who are tired and just don’t want to teach any more. Not just luthiers are needed either. Sergiu Schwartz, a concert violinist from Florida, went to teach at the behest of the South Shore Music Festival. They also made plans to send a quartet to play as well as coach. ’They need outside influences. They have been isolated during four years of war,’ Injeian explained.

The Philharmonic was reduced to some 40 musicians, too few to play the big symphonic pieces. Replacing musicians lost during the war has proved difficult. The supply of trained musicians in Bosnia had been exhausted, and the orchestra’s meagre finances just didn’t attract musicians living abroad. It has been financially dependent on the government and philanthropy.

In accordance with noblesse oblige, one would respond to other disasters, as Injeian did in 2010. Haiti suffered a major earthquake, 7.0 on the Richter Scale and devastating aftershocks followed. A death toll of over 300,000. The Holy Trinity Cathedral music school served more than 1,000 students before the quake. Injeian went to do what he is so good at: restore the instruments. He also gave intensive training to those who would repair instruments, inevitably needed for the future.

The boys’ choir went on a US tour to help raise support for rebuilding the school, which depends on charitable support. Humanitarian aid was forthcoming, spearheaded by the United Nations and the International Red Cross, and many countries in the region and around the world sent doctors, relief workers, and supplies in the wake of the disaster.

Among other examples of noblesse oblige was one on behalf of Sarajevo’s public library. The major damages effectively erased the historical references on its shelves. A compendium of US and UK librarians pooled their libraries resources. Duplicates of historical reference materials were then delivered there restoring access to the region’s history.

An example outside the world of music was in the aftermath of the more recent Hawaiian wildfires. The noble spirit of a jeweler manifested. Omi Chamdi immediately sprang into action and advertised free restorations. ’These are not just ordinary items, these are the most precious possessions that people go back to the ruins and dig through the rubble to find,’ he said. ’That’s why I feel this is something I want to do and must do, because this is within my expertise.’

Special thanks to Dr. Mary Pat Donegan for her help with this article.

All images courtesy of Phillip Injeian.

Read: Uncovering Arthur Foote’s Cello Concerto: Julian Schwarz

Read: The Viola’s White Knight: Hermann Ritter and the quest for the perfect Alto instrument

Read more lutherie articles here

An exclusive range of instrument making posters, books, calendars and information products published by and directly for sale from The Strad.

The Strad’s exclusive instrument posters, most with actual-size photos depicting every nuance of the instrument. Our posters are used by luthiers across the world as models for their own instruments, thanks to the detailed outlines and measurements on the back.

The number one source for a range of books covering making and stringed instruments with commentaries from today’s top instrument experts.

American collector David L. Fulton amassed one of the 20th century’s finest collections of stringed instruments. This year’s calendar pays tribute to some of these priceless treasures, including Yehudi Menuhin’s celebrated ‘Lord Wilton’ Guarneri, the Carlo Bergonzi once played by Fritz Kreisler, and four instruments by Antonio Stradivari.

No comments yet