For John Dilworth, a simple piece of willow or spruce can become a sanctum for covert messages

Discover more lutherie articles here

This article is from the May 2013 issue of The Strad

The top-block. Another simple piece of straight-grained wood, faced off nice and square, a straightforward task. What can possibly go wrong? Ah, I could tell you tales of top-blocks. Hidden knots, twisted grain, even upside-down grain. All these things can happen and not reveal themselves until you’re actually fitting the neck. The pain.

But still, top-blocks have interesting stories to tell. Some are pine, some are willow. Some have inscriptions, some have nail holes or peg holes. Some just don’t exist. The Amatis generally used spruce – scraps from the workshop floor, with three or four iron nails banged through them into the neck. But the Brescians managed without anything. The neck root goes through the top ribs and glues itself to the back. No block or nails required. And so it went. Now, spruce has its problems. If you accidentally fit the block upside down, as it were, with the angle of the grain in the wrong way, it’s seriously difficult to make the neck joint. And then, softwood splits very easily, especially if you’re pushing a dovetailed neck joint in a little too hard or hammering a handful of nails through it. Stradivari went for the more homogeneous willow as his material. But spruce or pine continued to be the usual choice elsewhere.

The fascination for me is that the top-block has always been a good place to plant discreet messages to other violin makers peering in through an empty endpin hole. Stainer famously pasted a label there claiming to have been a pupil of Amati. He didn’t, as far as we know, do it more than once. The Gaglianos often wrote a little prayer or religious dedication. Benjamin Banks branded it carefully. The most notorious copyists often chose the interior face of the top-block to reveal their true identity, as if they couldn’t resist showing off to their fellow craftsmen what they wouldn’t want the buyer to know.

What you see inscribed on the top-block is not always what you see on the label. It implies that makers imagined the top-block always to be a part of the instrument, a permanent part that only another violin maker would see, and a message board that has sometimes lasted for centuries. The top-block is fundamentally a shaping element of the structure, and has the most important job of all in keeping the neck in the right place. But through modernisation and restoration and neck replacements, top-blocks have been happily chopped away. It shouldn’t be necessary. Let’s have a bit of respect for the poor hard-working, battered, beaten and nailed top-block, the ‘dead letter box’ of the violin.

Read: Jacob Stainer: Micro-CT analysis of top-block and pins

Read: CT-Scanning the ‘Messiah’ Stradivari violin

Discover more lutherie articles here

This article is from the May 2013 issue of The Strad

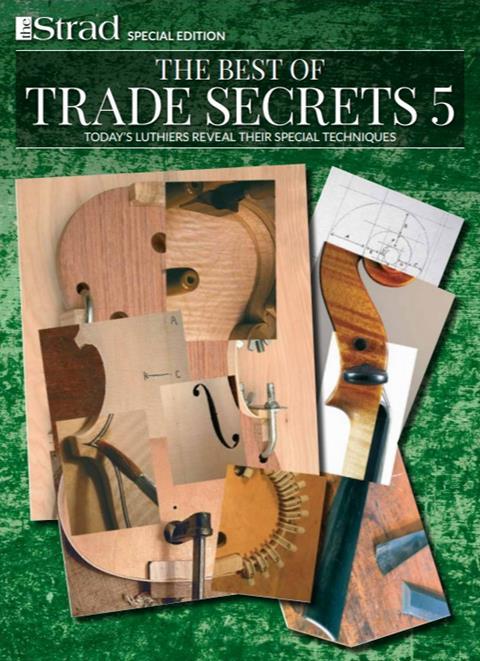

An exclusive range of instrument making posters, books, calendars and information products published by and directly for sale from The Strad.

The Strad’s exclusive instrument posters, most with actual-size photos depicting every nuance of the instrument. Our posters are used by luthiers across the world as models for their own instruments, thanks to the detailed outlines and measurements on the back.

The number one source for a range of books covering making and stinged instruments with commentaries from today’s top instrument experts.

This year’s calendar celebrates the top instruments played by members of the Australian Chamber Orchestra, Melbourne Symphony, Australian String Quartet and some of the country’s greatest soloists.

No comments yet